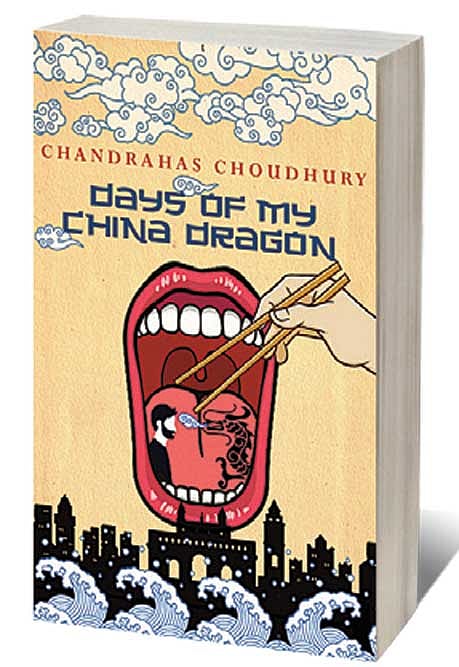

Mumbai Mouthful

CHINESE FOOD MIGHT as well be considered one of India’s many regional cuisines. Chicken manchurian and hakka noodles are beloved staples (if not sources of national pride), while street carts lettered with the Hindi chayniss provide a lifeline to many. In this culture dedicated to its own version of food from across the border, Chandrahas Choudhury’s Days of My China Dragon is about a restaurant that refuses to be just another Indian Chinese joint. Somewhere between a novel and a set of interconnected short stories, the book goes behind the kitchen door of Bombay’s gritty restaurant life, narrating the everyday chaos of owners, chefs, waiters and hard- to-please customers.

Each story follows a character or incident in the life of Jigar Pala’s restaurant, China Dragon, to present a quirky, often philosophical, portrait of a small business in a big city. Although the book’s premise is amusing, and the stories are endearing in pockets, the different vignettes soon begin to seem as though they are repeating themselves, at least in the small insights they wish to elevate.

Jigar Pala, an enterprising Sinophile trades in his father’s popular Udupi restaurant (in the Prabhadevi neighbourhood of Bombay) for a Chinese one. Given the tastes of a fast-gentrifying city, a made- in-China version of the family business, Pala believes, holds better economic prospects. ‘Chinese is big business,’ he says, ‘Virtually the second cuisine of India.’ But unlike its counterparts, Pala’s restaurant boasts of authentic, well-researched Chinese recipes, some even collected from Bombay’s Chinese migrant families. He wants his customers to ‘walk out feeling as if they’ve just been to China’. Enthusiastic as Pala is about his new gastronomic vision, his restaurant struggles for clientele. Of course, when ‘the bestselling item in all Indian Chinese restaurants is paneer’, he must convert a population that believes Chinese food tastes better in India.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Told in Pala’s voice, the stories affirm the dream of the restaurant. In one, he scouts for a real dragon to bring luck to the fledgling venture. In another, he remembers how he battled legacy and familial expectations to forge his own path. The eccentric staff from different parts of India and Nepal grow tighter knit into a family. These different episodes reveal that a restaurant is always more than a restaurant—it is a journey, of both pilgrimage and exile, and a microcosm of the world it feeds.

‘A restauranteur’s job,’ Pala says, ‘is to make not just food but time warm, alive, nourishing.’ His ontological musings about Tao intersperse his recollections, as if to imbue everyday quirk with a higher purpose. A plate of small dim sum or green tea chicken— authentic samplings imported into a quintessential Indian Chinese restaurant— unravel into crises of identity and politics. They become a metaphor for Bombay itself. For its confluence of people, their hopes and their struggle to thrive amidst big development.

The project of addressing gentrification and class aspirations through the aromas of food and the sagas of empty tables and property sharks often feels lofty. Pala, rather than being a multifaceted character in his own right, is left more as a narrative device. At one point, he even becomes a mouthpiece for anti-Shiv Sena ideology when he reprimands— at length—one of his young workers for joining the activities of a local xenophobic Hindu party. The history lesson on Shivaji that follows seems all too forced.

Choudhury’s writing is light. Many of his characters and scenes are colourful. And it is a relief to read an Indian restaurant story that doesn’t labour on needlessly with overwrought descriptions of food. Deft as the sentences are, though, the interactions between characters are not complex enough to sustain the philosophy. Nor is the philosophising diverse enough to work as first-person lecture. The restaurant—such a concentrated setting—is unable to deliver morsels meaty enough to make a meal.