Many Indias

EVERY ANTHOLOGY RELIES on a marketing gambit to justify its existence, which is usually signalled in its title. Think of the now-iconic The Best American Essays series, which has appeared every year since 1986, as a showcase of the finest non-fiction writing from the US.

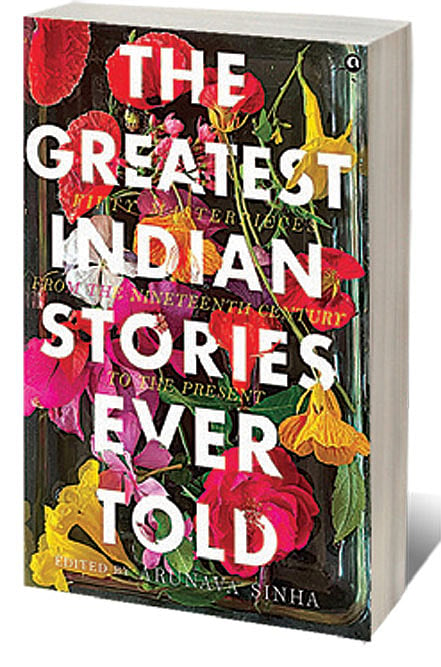

The Greatest Indian Stories Ever Told, edited by Arunava Sinha, follows the same strategy, except with much more audaciousness. In fact, the scope of the Best American Essays begins to sound rather coy compared to the combined hyperbole of the title and subtitle of Sinha’s anthology (Fifty Masterpieces From The Nineteenth Century To The Present, the latter goes).

Literary historians broadly agree that the short story as a form began to emerge in the nineteenth century, fuelled by the popularity of periodicals, magazines, and journals. Sinha’s timeframe, by this logic, makes eminent sense. But since he doesn’t date the stories, it’s difficult to sense the evolution of the form in India through the decades. More troublingly, contrary to the promise of the title, the introduction makes a somewhat confusing case for the unity of the volume.

This selection of stories, Sinha tells us, “does not emphasize the quality of being the ‘greatest’ in terms of each individual story, but in terms of the complete set.” Indeed, as he goes on to argue, “the diversity and the variances” in the selection actually serve to bring credibility to the title of the anthology. “To re-emphasize, the stories here have not made their way into the volume on their individual strengths—which are, frankly, unquestionable—alone but also because each of them contribute a piece to the puzzle that is the literatures of India,” he adds.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Serious readers of literature are unlikely to split hairs over clickbait titles, but Sinha’s line of argument, see-sawing between assured self-confidence and a subtle disclaimer, complicates the reading experience. But thankfully, there is much to discover and admire in this collection, primarily because 43 out of the 50 stories included are in translation. By casting his net wide, Sinha, who is a translator himself, reveals the source code of India’s literary modernity: the sea of stories that flows through the veins of this nation, told by many voices, and in many languages.

The linguistic diversity of the collection ranges from Urdu to Malayalam to Assamese and even Portuguese (as a nod to Goa). The opening story, Siddiq Aalam’s ‘Two Old Kippers’ (translated by Muhammad Umar Memon from the Urdu), sets the bar high with its fine undercurrent of existential bathos. The last story, the disturbing ‘Bhaskara Pattelar and My Life’ by Paul Zacharia (deftly translated from the Malayalam by Gita Krishnankutty) brings down the curtains with as much aplomb.

In between there is much to move the reader. Mannu Bhandari’s ‘Trishanku’, in Poonam Saxena’s beautiful translation from the Hindi, and Ramnath Gajanan Gawande’s ‘Tale of a Toilet’, in Vidya Pai’s translation from the Konkani, stand out as droll but tragic tours de force. In contrast, Anna Bhau Sathe’s ‘Gold from the Graves’, translated from the Marathi by Vernon Gonsalves, is macabre and almost unreal in its unravelling, as is Bhabendra Nath Saikia’s ‘Rats’ (rendered from the Assamese by Gayatri Bhattacharyya). Among the English writers, Shashi Tharoor shines with ‘Charlis and I,’ a throwback to his years as a gifted storyteller.

While the selection, by and large, speaks for its discernment, there are inevitable omissions. Perumal Murugan, Jayant Kaikini, Kalpana Swaminathan, Rohinton Mistry, Anita Desai, and Ambai are some notable misses for me. On the other end, there are some obvious concessions to populism. Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Kabuliwallah’ makes the cut over so many of his far more superior stories. ‘The Booking Counter’ by Mamang Dai isn’t her strongest work, as is the case with several others, like Kalki and KM Munshi. More rigorous sifting and thorough research would have taken this anthology closer to what it aimed to be.