Love After Death

What happens to those we love when they have died? Do their souls pass blissfully into an illuminated heaven or a blissful nirvana, never to commune with us anymore? Do they cut all ties to what bound them to earth, to friends and family? Or do they, perhaps, linger on? Not as those benevolent (or otherwise) spirits that hover about, occasionally glimpsed or heard, the stuff of chilling stories?

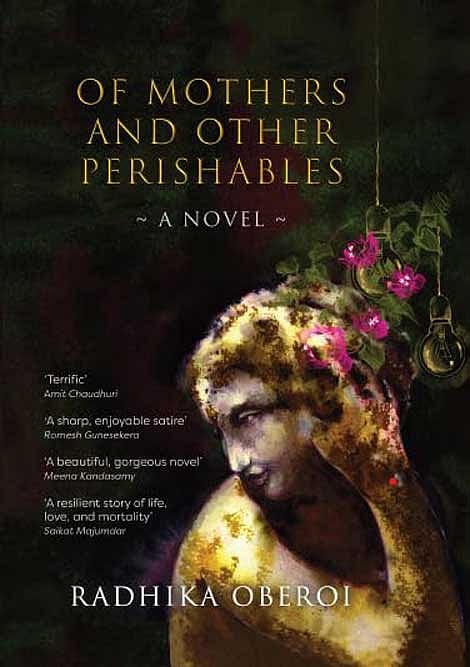

Or perhaps, as in the case of the part-narrator of Radhika Oberoi’s Of Mothers and Other Perishables, they do linger around us, but are never seen, never heard. Only felt, perhaps, and that too vaguely tangible. This narrator is a woman who died of cancer in the spring of 1993, but who continues to inhabit her marital home. She lives—or does not live—in the locked storeroom where, wrapped in muslin, are her saris. Where, too, there are the memories of many decades: photo albums and memorabilia of weddings, birthdays, the childhood of her two daughters.

These daughters are never identified by their real names, but their personalities (as that of their mother, and of several other characters) is sharply etched. The elder daughter’s nickname is The Wailer, after Bob Marley and the Wailers, because she wailed so much and so easily. Her younger sister, addicted to cartoons, is called Toon. The Wailer was sixteen when their mother died; Toon nine. Now, it is the Wailer, creative director with an advertising agency, who keeps the storeroom’s keys and visits it every now and then to refold her mother’s saris, to dip into the past, to perhaps share her woes with the comforting dimness there. Toon, working at a coffee start-up and having an affair with her boss, had drawn away from the Wailer long ago, the schism now so wide between them—though they live in the same house with their widowed father, LP—that the two sisters rarely cross paths.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The story is told in two alternating voices. One is the third person, which narrates the story of the Wailer, in the present: in 2020, when the Shaheen Bagh/Kalindi Kunj anti-CAA protests are at their peak. The other is the first person, the Wailer’s long-dead mother, remembering her past: her romance with LP, their wedding, her daughters. And, as is common with the living too, intertwined with that are her comments on the now: on her daughters now, LP now, their lives.

Two narratives, two time periods, two points of view. The mother’s is more personal, more tied to the home and to family; the Wailer’s meshes with her work at the agency. The dynamics at the agency; the suffocating isolation of a talented woman in a ‘beefy boys’ club; the Wailer’s attempts to assert her creativity without kowtowing, yet without being abrasive: these form the basis of her narrative, until that landmark evening when a colleague, known as the Nawabzada, takes her along to Kalindi Kunj.

The nature of grief, the way people deal with bereavement, and how it affects them, forms an important element of this novel. Oberoi, however, handles this with sensitivity and compassion, using occasional wit and a deep understanding of human nature to veer the narrative away from possible melodrama. The story is uncomplicated, moving in an organic, quiet way; what makes it so engrossing is the skill with which Oberoi weaves that tale: the way her characters come alive, the relatable memories they have, the relatable emotions that grip them. The way love and empathy eventually come to the rescue. The humanity which surfaces (and, also, the greed and selfishness which elbows its way to the forefront): all of it so true, so very real.

It is, too, a subtle comment on other matters: on workplaces (and working women), politics, India and Indians today: so obsessed with moving up, with material possessions.

A highly readable, impactful book.