Life Is a Forest

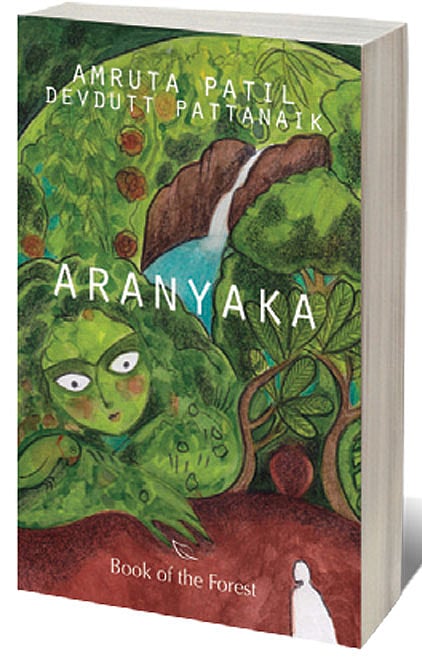

ARANYAKA, A GRAPHIC novel written jointly by mythology mavens Amruta Patil and Devdutt Pattanaik is a difficult book to review. I have been sitting with it for the past three weeks, hoping, as time went by, that I would have something eloquent to say about it. ‘Luminous’, perhaps, that old standby blurb favourite. Or ‘dazzling and competent’, all great words and all words that apply to Aranyaka, but I felt I’d be doing the reader a disservice by not going deeper, further, to tell you how this book made me feel.

Together, Pattanaik and Patil picked an Upanishadic story of a sage called Yagnavalya, but used him just as inspiration to inform the larger story, which they invented. As Pattanaik writes, ‘We, as a people, are highly territorial about Upanishadic narratives, and violently puritanical.’ Therefore, the choice to leave it vague.

If Aranyaka were a Shakespeare play, it would be Antony and Cleopatra, but without the tragic ending: two lovers who do not understand each other and ultimately part ways, which I suppose is a tragedy of a sort too, just a quieter one. But that seems unfair to the protagonist of Aranyaka, a plus-sized, feminist heroine named Katyayani, with long tangled hair and sexy wide hips. Like Cleopatra, Katyayani falls in love with a man strict and severe with himself and others. While he lives with her and they have children together, he is also a great teacher and people flock to learn from him. More and more, this man, who Katyayani refers to as ‘Y’ throughout, longs to separate himself from the trappings of a home and a family. Her kitchen is a point of contention, her cooking smells distract the students, new female students come along and she knows her partner likes them, respects them—especially two: The Weaver and The Fig—and she struggles with jealousy. Mostly it’s the story though of liberated women, even in Vedic times: how each of the women—The Fig or The Weaver or Katyayani herself—is carving out paths for herself, whether through learning or cooking, listening to the forest or debating with the teacher.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Aranyaka is a gorgeous book. There’s a woman, who loves to eat and love and cook and be; and she meets a sage in the forest and they start a life together, but the forest, the aranya of which this story is told, is both background and structure. All life is forest: all creatures eat or are eaten, all of us nurture or are nurtured and so on. It’s important to remember this message, in this far-off future year, where ice is melting and forests are burning and the very air is choking us. The forest is still there, even if you can’t see it, and the aranya is still waiting for us to let it return.

Meanwhile, there’s so much more going on in this book than I can explain. The women all look different from each other (like real women!), something which makes such a difference when you see it drawn out in front of you.

Perhaps I am too used to Amar Chitra Katha versions of women, all in-and-out waists and the same faces drawn over and over again in different shades. Everyone argues, but they argue with reason, with learning, another thing I miss in this angry Facebook world. And so, I would say Aranyaka is comforting. But then I turn another page and I am thinking hard about something a character said, and so, I would say Aranyaka is challenging.

Here’s what it’s not: a comfort read, something where you know what you’re getting into. Rather, it’s a little like the forest it’s named after: vast (not literally, it’s a slim book) and with many roots under the surface.