In Search of Meaning

Words don’t always mean what they are supposed to—especially in poetry. Disparate things are compared in metaphor or simile. Stanzas move image and location, not always in logical ways. And, somehow, disjointed ideas can be the very things that offer insight. Poems are formed of associations; they allow language to be repurposed. These two books of poetry (containing poems of two very different languages and eras) show two distinct approaches to altering words and what they are supposed to mean. Neither follows a narrative approach. Rather, these poems are concerned with building new associations between word and meaning.

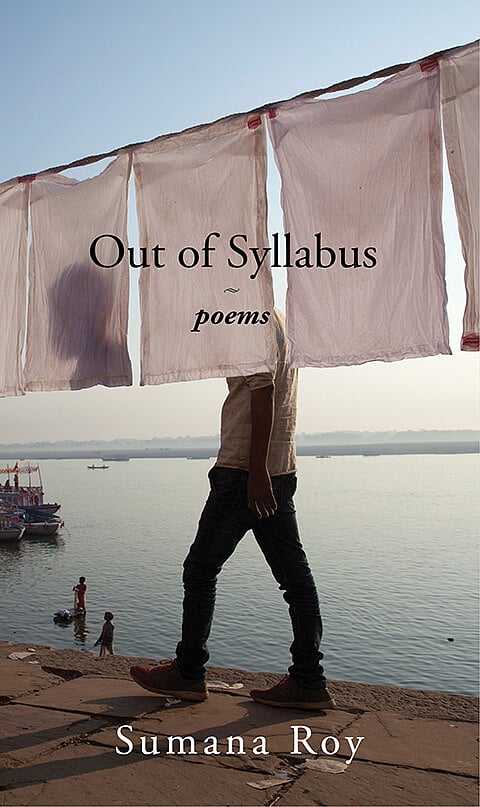

Out of Syllabus | Sumana Roy

The witty title of Sumana Roy’s collection immediately brings to mind an idea that any person who attended the average Indian school would understand—what is ‘out of syllabus’ is the unnecessary matter, the wayward ideas, the lessons one needn’t learn by heart. The collection thus declares its subversion, and draws up an alternate syllabus to the one most of us, especially women, are told to live by.

The poems are divided up into 15 periods of a school timetable, from mathematics to biology to history to moral science, and finally, art. This movement from foundational subjects towards ars poetica is a calculated one. It is an unlearning toward a new picture of the world. The last poem points out, ‘There are more poems about the moon than wives’—with another education, perhaps our canon would be different. That isn’t to say that the collection is itself a moral lesson standing in for the ones it decries. Instead, it wants to be a series of portraits of what we know but never learn about.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In Dancing Girl, Mohenjodaro Roy deconstructs the famous Indus Valley sculpture to show that we have learned of this artefact only as an object of the male historian. ‘History, like paedophelia, has a way of turning girls into women,’ Roy writes, ‘For man is like Time, impatient for chests to grow monuments.’ By inserting the bawdy into the pristine definition of history, she attempts to reconfigure its meaning, from something institutional to something inhabited—‘History, like desire, is all inside.’

Similarly, in each poem, Roy uses comparisons to dismantle words as we know them. The similes are deliberate, the dissonance intended. In this exercise Roy doesn’t simply redefine subject area, but also understandings of everyday experiences—what it means to touch, to lust, to be an adult. In The Lexicographer in Lower Assam, she clarifies, ‘Meaning is always elsewhere.’

Occasionally, Roy’s lexical arrangements are striking. Every Girl Is Dinner concludes:

‘The alliterations in a pair: rape and rage,

cannibal lust, carnivorous anger,

words, the world as a slaughter house,

violence as scansion, violation as eating.

Woman as kebab, woman in a tandoor.

And I wait, a living carcass,

my life bullied into cold storage,

to surrender my meathood.’

Womanhood here is traded in for meat and brutalised, systematically and syntactically. And so, this vision that has been deliberately kept out of syllabus and out of sight, appears as a reality to be reckoned with.

But not every poem in this collection manages move beyond its construction. Although the project is one of reclaiming figures of speech and rewriting language, more often than not, the word play ends as profusion. Long poems (as Roy’s are) unfairly get a bad reputation, and the length of the poems in this collection isn’t the problem. Instead, it is that within the length, the crafting of each idea isn’t necessarily deft. Lines like ‘Stranger,/make me a lie,/make me your heart,’ in an attempt to be assertive, come across as indelicate. And the many wild metaphors often read as either overwrought or abstruse. There are a few gem-like epiphanies in the collection, but to find them, one has to make an effort to stay.

Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms New & Selected Translations | Sudeep Sen

In the year that marks Urdu poet Kaifi Azmi’s 100th birth anniversary, several English translations of his work are appearing in bookstores. Rakhshanda Jalil’s translation titled Kaifiyat has now been followed by Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms, which compiles the work of five different translators—Husain Mir Ali, Baidar Bakht, Sumantra Ghosal, Pritish Nandy, and Sudeep Sen (who is also the editor). The collection poses not just as a celebration of Azmi’s work but also of translation.

Each translator’s renditions are preceded by a translator’s note or one by Sen. These expose the concerns of each translator and allow for a comparison between their different methods and readings of the same poet. At first, this seems like an interesting idea, but none of the translations stand up as poems in themselves. Beyond hackneyed debates about being faithful to a sacrosanct original, these translations do not grab attention on their own—one only seems to consider them in relation to what we know of Kaifi Azmi’s importance in modern Urdu literature.

Contextual understanding is essential to reading Azmi’s poetry, whether in English or Urdu. Through different poems, he repeats certain images and metaphors that hold peculiar meaning in his work. The revolutionary who muses through the night, or the beloved as the fellow revolutionary are just some of the tropes that speak to Azmi’s anti-colonial and communist politics. (He was a card carrying member of the Communist Party of India and even lived for a period in a commune with his wife.)

Azmi draws references to different places and archetypes within a single poem, which can seem particularly jarring in translation. In the same poem, he could speak of the lover’s body, the public street, and funeral pyres, without warning. But that impulse is typical of his work; the tender is always in conversation with the political, and love and revolution are synonyms.

Given the metaphorical complexities and self-assigned double meanings, anyone translating Azmi needs to work particularly hard at making the translation accessible. That is where much of this collection disappoints. Preoccupied with a balancing act between literally translating imagery and also conveying subtext, the English often seems stilted. Ali, who focuses on Azmi’s overtly political poems, translates a stanza of ‘Unemployment’ (Bekaari) like this:

‘It’s my bones that were used to make these palaces

It’s my blood that has produced the freshness of spring

This glittering wealth is built upon my poverty

These shining coins require my dispossession’

While it would be nearly impossible to recreate the rhyme of the Urdu, the translation also does away with a certain poise. The word choices render the stanza almost clinical, neither alluring the reader nor giving them a sense of the rousing spirit the stanza intends.

Similarly, Bakht, who admits to choosing ‘faithfulness’ over beauty while translating, gives us poems in an outmoded register of English. Being faithful to the original is hardly an excuse for falling back on phrases like ‘cure my heart’s affliction’. Ghosal, while a little lighter with his English, too, doesn’t consider the emotional register of lines carefully enough. He translates the penultimate line of Azmi’s seminal poem Aurat (Woman) as:

‘How long will you hesitate?

The moment to assume control is here, now.’

What should have been a loving call to action is stripped of any intimacy.

Nandy is perhaps the most successful in giving us poems that are comfortable in English. Although inconsistent, his translations are at least able to command some attention from the Anglophone reader. For instance, his opening of Bangladesh stands out:

‘I am not a country you can set ablaze,

I am not a wall you can raze to the ground

nor a frontier you can obliterate.

This obsolete map of the world

spread before you on the table

is only a maze of wayward lines.

How can you find me here?’

The final set in the book is Sen’s translations. Unlike the other translators, he says his ‘barometric impulse has been that [the poems] should read like good poems in English.’ If only he had been more successful. He opens Two Nights (Do Raatein) like this: ‘Jumbled-confused emotions, ask not about them./Scared frightened favours, ask not for them.’ Although concise, the syntax is hardly that of an English at ease—a problem that runs through most of the translations.

Azmi’s poetry, famous for a lexicon that spans the heightened and the restrained, once again, fails to come alive in a foreign language.