Data Capitalism

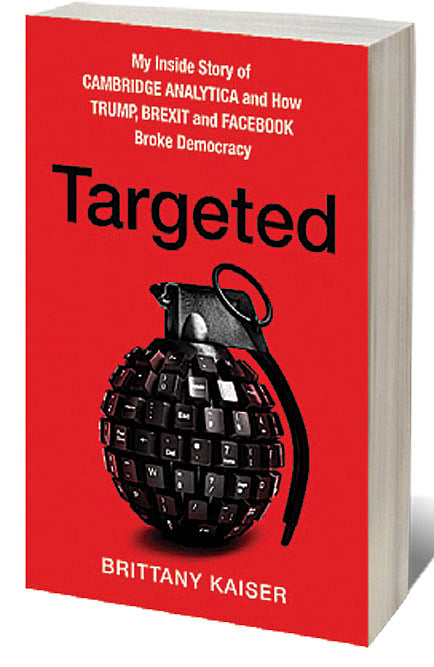

SOME TIME AGO, I reviewed a book by a whistleblower from the tainted political consultant and voter-profiling firm Cambridge Analytica (CA). Christopher Wylie’s Mindf*ck: Cambridge Analytica and the Plot to Break America was a great read indeed. Yet, the book being reviewed here, Targeted: My Inside Story of Cambridge Analytica and How Trump and Facebook Broke Democracy by Brittany Kaiser, the former Director of Business Development at the company that steered a highly polarising Brexit and Trump presidential campaigns besides others, offers greater insights into the nefarious ways of the British consulting firm thanks to her position and access she had to the CXOs, including the upper-class chief executive Alexander Nix, who considered her a friend. The common thread between Wylie, who is hated by CA’s top execs, and Kaiser, who has so far not come under any major attack from her former employer, is that they were both liberals in a conservative setting. Unlike Wylie, for Kaiser, who calls herself an out and out ‘Democrat’ and who has worked with humanitarian organisations in the past, what runs deep is a sense of guilt. She can’t hide that in any of her 20 chapters. ‘Did I have to do this?’ That seems to be the recurring theme in the book, which also uncovers secrets about the workings of CA, which specialised in election campaigns and manipulation of human behaviour based on data they accessed from numerous sources, most famously from Facebook, the biggest aggregator of behavioural data.

What CA did was simple when you consider this scenario: you use your credit card to shop at a grocer or a chemist or a book shop. Naturally, all these shops sell your purchase details to data aggregators for a fee, who in turn sell these to firms like CA, again, for a fee. This is how data is monetised at each level to predict or analyse behaviour—or both—to create ads on Facebook or elsewhere to further influence buyers. A company like CA uses that information and matches it with your online behaviour to assess whether you are a political fencesitter. If you are, then they bombard you with ads and promotions to make you veer towards their side. You don’t know what is happening, but they are manipulating you to shape your short or long-term voting choice. Instilling fear and hatred, of course, are the easiest routes to get the best results in this game. Those who target you, especially in a wired world, use principles and methods of psychometrics and psychographics to feed you with news and views to heighten your anxieties to help pull in your vote in favour of their clients.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

All this—including sharing of data that you assume is private—is done without your consent, especially in the US where you pre-opt to share almost all online and credit card transactions. Unless you had read the fine print, you would never know the trap. What happens later is the centralisation of data—a trillion-dollar industry—by companies to swing results in their clients’ favour.

Despite her political slant, Kaiser gives a personal reason why she chose to work for Nix and his conservative friends. A quintessential liberal, she experienced continual culture shocks within the firm, she says, but stayed on to help her family wade through a massive financial crisis. Kaiser, who was in her 20s when she joined CA and worked for four years in a key post, also found Nix to be highly charismatic. Her admiration for Nix’s persuasive skills comes through in the book, although he had powerful friends—including Steve Bannon, the high priest of neoconservatism—whom he helped in their divisive strategies. Anyhow, Kaiser recalls Nix often telling her that data is the new oil. His idea was to weaponise data to meet his goals by hook or by crook.

This is what Kaiser says about the condition of her family when Nix asked her to join him, impressed by the fact that she had worked in Democratic campaigns before, including the highly successful Obama presidential bid of 2008. ‘There are a variety of reasons why I allowed my values to become so warped—from my family’s financial situation to the fallacy that Hillary would win regardless of my efforts or those of the company I worked for… Perhaps the truest reason of all was that somewhere along the way I had lost my compass… .’

Besides, despite their different backgrounds, Kaiser and Nix gelled well. Kaiser, who has degrees in human rights, law and international relations, was unafraid of entering, what she calls, the high-stakes, high-testosterone arenas—she had worked in politically volatile and dangerous countries in Africa and had even helped North Koreans escape bondage through China to Hong Kong. Nix, on the other hand, she explains, ‘emerged from a closed society of young, privileged men destined to operate in a world of others who looked like him’. In the 18th century, Nix’s family had made money from the East India Company. And they stayed rich all along. Besides, he went on to marry a Norwegian shipping heiress. Interestingly, the pages that talk about how the two became close associates reveal a lot about Nix’s leadership qualities and Kaiser’s maverick nature. Which is why this book is a credible account of how the top leadership of CA worked. For instance, Nix once told Kaiser it was Sophie Schmidt, daughter of the then CEO of Google, Eric, who was ‘partly responsible for inspiring the inception of Cambridge Analytica (from its parent SCL Group)’.

Kaiser’s book offers several behind-the-scenes details of Nix’s networking skills and connections in high places—and his earlier contracts to run election campaigns in countries such as Nigeria; early wins in the US (thanks to its data analysis services for Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign), among others.

Kaiser also sums up what Nix promised his clients: ‘Alexander’s company looked at people to determine what they needed to hear in order to be influenced in the direction you, the client, wanted them to go.’ CA employed psychologists, who, instead of pollsters, designed political surveys and used the results to segment people, Kaiser writes in the book. The next stage was modelling. Which meant that the company’s data gurus would create algorithms that could accurately predict ‘targeted’ people’s behaviour when they received messages crafted for them. Perhaps to lure Kaiser, a liberal, Nix disclosed to her a part of the company CV that impressed her: Nix and team had worked for Mandela in the landmark 1994 South African election to contain likely violence through proper communication.

Certain anecdotes from the book are thrilling. For instance, after coming to know that Kaiser was an activist for the Democrats from a very young age, Nix tells her handing over his card, perhaps setting the tone for a longer association: ‘Let me get you drunk and steal your secrets.’ Immediately, Kaiser sensed that he was only half joking, she writes.

After the Trump campaign was over, things started hurtling towards mayhem with charges being levelled at CA—all that is now in the public domain. But Kaiser narrates a blow-by-blow account of how the company unravelled, thanks to her proximity to each event, including top-level inquiries that followed, and about her and Nix growing apart.

The last chapter, ‘The Road to Redemption’, is where Kaiser wonders what actually went wrong. She writes, ‘…I had compromised myself and thrown away my moral compass—and I had not even been paid well to do it. How had I been so blind?’ But she felt free after quitting CA. And she was ready to pick up the pieces. Then she found a new calling: as co-founder of the Digital Asset Trade Association to help protect the rights of people to privacy and to ensure they have control over their data.

In these times—especially when the likes of Nix are increasingly acquiring legitimacy to function and still blame the ‘liberal media’ for witchhunts against them for all conspicuous crimes and malpractices—this is a book that is not just to be read, but re-read.