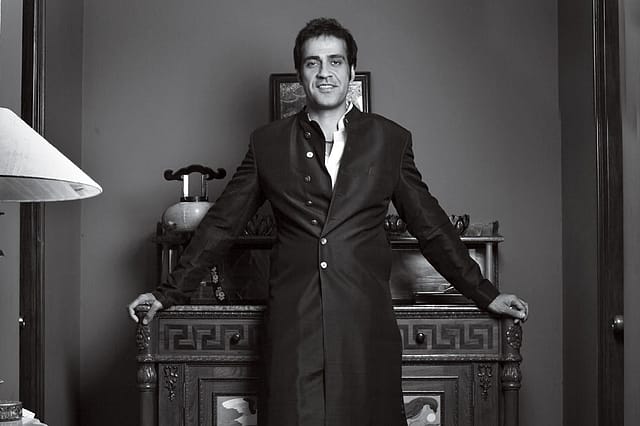

My Choice of Best of 2019 Books: Aatish Taseer, Author

PEOPLE WILL ALWAYS look different from one another in ways we can't control,' wrote Thomas Chatterton Williams in a New York Times essay, drawn from his marvelous memoir, 'What we can control is what we make of those differences.' Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race is a reckoning with both the illusion and reality of race. Williams is a wonderful, lyrical writer—the scourge of Ta-Nehisi Coates, I may add—and he gives the idea of race an almost metaphorical power, so that it speaks directly to someone as myself, who grew up half-a-world away, straddling a different but equally volatile fault line. James Baldwin and WEB DuBois are among my favourite writers in the world because they are able to use the prism of their specific historical situation, turning it into a meditation on the human condition. Williams writes into that same tradition and the result is exhilarating.

It is rare to have a new old book, but that is precisely our good luck in 2019. Koestler's 1940 classic, Darkness at Noon, was among the earliest and most severe indictments of Stalinism. The book we read however was not the translation of the German original, which was believed to be lost, but rather a hastily completed English translation by Koestler's sculptor-girlfriend, Daphne Hardy. Koestler had finished the book 10 days before the German invasion of Paris, then made a Casablanca-style escape to Britain through a Europe seized by Nazi terror. When he died by his own hand in 1983, he and everyone else believed the original manuscript of his modern classic was lost. Three years ago, a doctoral student named Matthias Wessel stumbled upon the original in the archives of Europa Verlag—Koestler's publisher—in the Zurich Central Library. What we have before us now, published by Scribner, is the first English translation of Darkness at Noon from the complete German manuscript. And I'm happy to inform you that it's great. The language is far less stilted and wooden. The themes, which are about the pressures of ideology on truth, are still electrifying. 'What is true is what serves mankind,' says the protagonist Rubashov's interrogator, as he marches him towards his own death, 'and whatever harms it is a lie.' This and other prescient sentences, such as, 'In periods of relative immaturity only demagogues manage to invoke the 'higher reason' of the people,' gives the new Darkness at Noon a fresh urgency, even as it makes the need for a Gujarati translation something of earth-shattering importance.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Also Read

Editor's Books Choice ~ by S Prasannarajan

Best of 2019 Books: Politics ~ by Siddharth Singh

Best of 2019 Books: Crime Fiction ~ by Shylashri Shankar

Complete List: My Choice of Best of 2019 Books

2020 Books Highlights: Fiction

2020 Books Highlights: Non Fiction

Best of 2019: Cinema & Series ~ by Rajeev Masand