Capital Noir

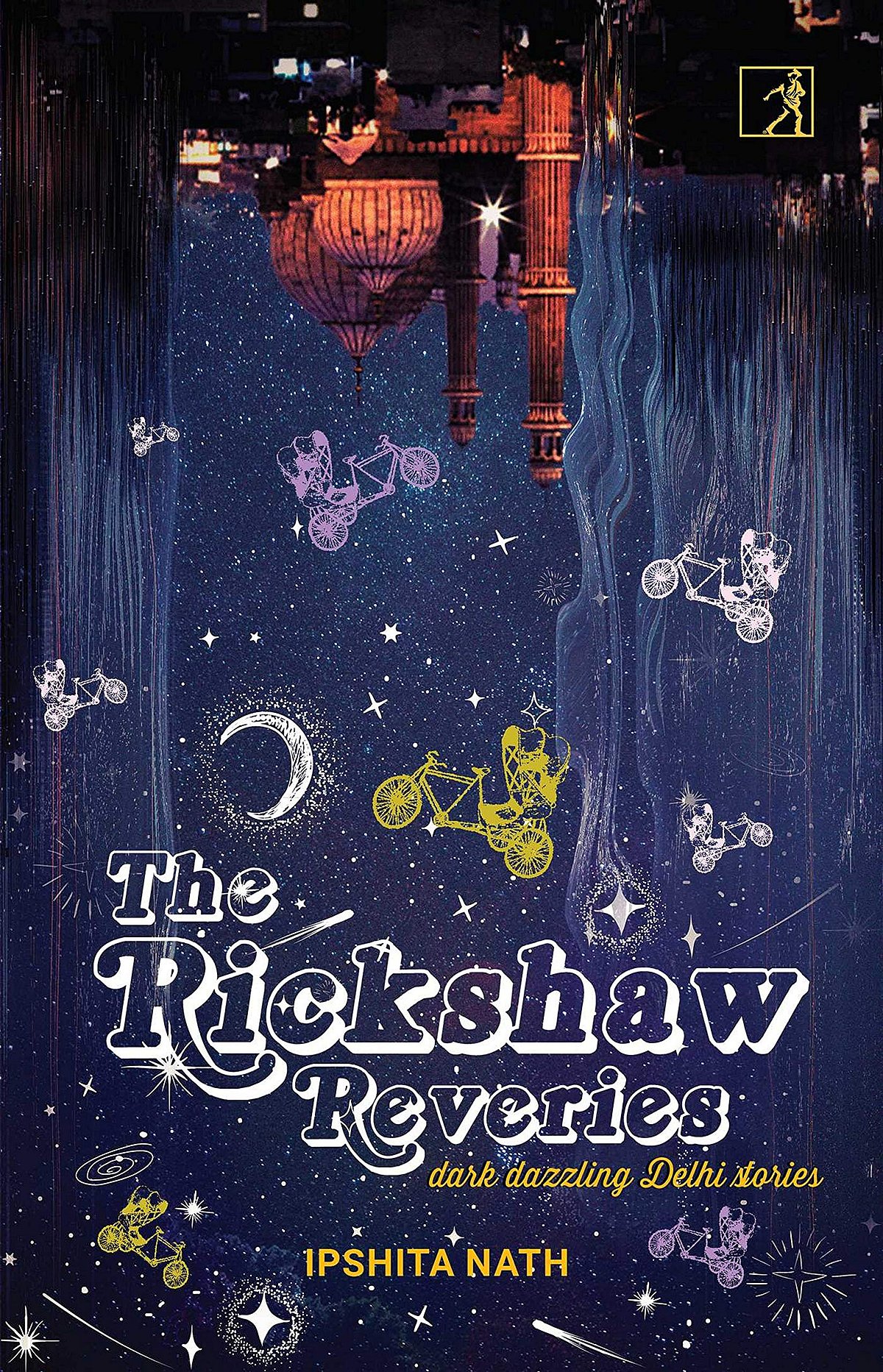

The Rickshaw Reveries is a collection of twelve short stories written by Ipshita Nath, who teaches English Literature at Delhi University. Her fascination with Victorian writing and noir fiction is evident in her narrative style, which lures the reader into a world where the boundaries between consensual pleasure and sexual violence are disturbingly blurred. All the stories are set in Delhi itself; the people who make them come alive are rickshaw drivers, sex workers, diplomats, pigeon whisperers, sculptors, fishermen, garbage collectors and perfume sellers.

Nath’s intimate knowledge of the city seems to aid her evocative descriptions of street life. Describing the milieu her characters live in demands a high level of skill in terms of reading people across class backgrounds, and the unique character of each neighbourhood. The stories unfold over a wide geographical expanse that stretches from Jamia Nagar to Sainik Farms, Chhatarpur to Chandni Chowk, Mayur Vihar to Khan Market.

What binds them together is the painful act of remembering that dreams die each day in an unforgiving metropolis that believes in the survival of the fittest. People come from afar to make money or a name for themselves but end up losing their moral compass in the bargain. Those who grow up there itself are haunted by the past, which is more like a bloated corpse than a photo frame in sepia-tinted glory.

Nath succeeds in filing away all that is broken in Delhi—drainage pipes, the criminal justice system, and relationships of various kinds. However, this is not social critique through fiction. It is an obscene fetishisation of suffering. Acts of rape and murder are presented in graphic detail, appealing to a voyeuristic imagination rather than evoking empathy for bodies that are brutalised and lives that are ruined.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

Given the current conversation around the #boislockerroom revelations on social media, it is worth noting that this book could be triggering for individuals who have experienced sexual assault. It presents narratives of victim blaming without addressing how these thrive within the broader patriarchal context of rape culture. Victims are sexualised in ways that make it seem like they were asking for it; this kind of insinuation is unacceptable. Their sexual agency is punished with violence and death.

One of Nath’s characters is a vigilante who wants to castrate all rapists in Delhi. He stores their mutilated organs in his house. His mission is fuelled by the pain he carries from being unable to protect his daughters from being raped by relatives. Another man is gangraped by monkeys in a forest. His wife refuses to trust him; she considers it impossible for a man to be raped.

The argument that a fiction writer’s job is to tell a story, and not concern herself with the ethics of writing about rape, is questionable. The most unsettling aspect of this book is how seamlessly it moves between recording a moment of lovemaking between two men in a public place, and rape by cops who discover them, without inviting readers to consider the victims’ point of view or their resistance to abuse of power. In another instance, the rape of a sex worker is justified by referring to her choice of profession, without exploring the hardships involved in a life on the margins.

Nath focuses on the physical aspect of sexual violence instead of exploring alongside its impact on mental health. Victims are rarely seen as survivors because the stories do not make space for their resilience or healing. Rape is depicted as a burden victims live with in case they do not die. The ones who do find closure get it only through retributive means that continue the cycle of violence. Should the onus to break out be on the storyteller alone, or society at large?