Amitava Kumar: Seeking Truth Between the Lines

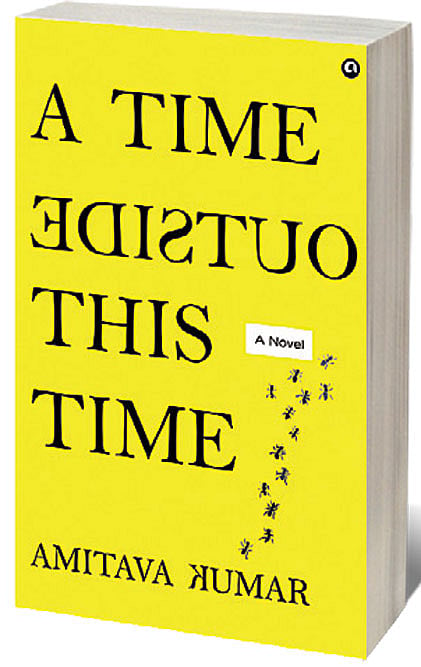

THE LINE BETWEEN truth and fiction is often blurred. This concept has always been significant in award-winning writer and journalist Amitava Kumar’s books, such as in A Matter of Rats: A Short Biography of Patna (2013) for instance, or Lunch with a Bigot: The Writer in the World (2015), and Immigrant, Montana (2017). Yet it is in his latest book A Time Outside this Time (Aleph; 272 pages; ₹ 394) where this idea is explored most thoroughly.

The narrator of this new novel is Satya, an Indian writer based in New York. Satya is frustrated by the rise of fake news during the presidency of Donald Trump, by the accounts of the frequent riots and lynchings in India, and the polarising leadership of both countries. At a writers’ retreat in Italy, he starts to write a novel Enemies of the People, where he examines the concept of fake news. In his research he documents and fact checks every piece of news information he hears.

At the villa in Italy, Satya is at first reflective; then the mood changes as news of the pandemic comes flooding in and throws everyone into a vortex of panic, anxiety, and fake news can’t be far behind.

“I wanted my story to be overwhelmed by this news story, which has become our common story,” says Kumar, 58, in an interview with Open via Zoom. From his house in Poughkeepsie, opposite Vassar college in upstate New York, Kumar’s conversation is as measured and thoughtful as his meticulously written new novel. Classes have resumed at Vassar, so, as he admits, some semblance of a normal working routine has returned. Fake news, however, is still very much of a reality.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

Speaking on A Time Outside this Time, he says, “I thought there has to be a response to the pandemic and what WHO calls the infodemic, the spread of the virus and fake news. That was a question for me, for literature. How do you respond to this sort of fiction if you are writing fiction?” Kumar’s aim was to draw closely from life and create a testament of the times we are living in.

On reading Satya’s notes on a MIT study that false news on social media spreads six times faster than the truth, the questions that arise are: is this a result of the times? Is this because of social media and technology? Or, is it simply an intrinsic aspect of human behaviour? Kumar agrees that social media is an instrumental factor; but he does not believe it has been as important as the rise of populism and ideologies that promote divisions. The potential for the spread of fake news has always existed; technology has only given it speed. “Technology aids this rise, but it’s also due to inherent weaknesses in people’s nature or collectively in a society,” adds Kumar.

In the book, Satya explains his goal cogently. “I use what is called real life to craft my fiction” to challenge and deconstruct the fake news narrative. He adds, “I am unable to invent fictional situations. Real life, even ordinary life, is what fascinates me, the low road of journalistic observation.” The methodical and journalistic approach Satya follows in his research and the way he presents his facts proves that he lives up to this ideal, even when the anxiety of the initial months of Covid peaks. While the book begins in the early months of the 2020 pandemic, it covers the initial tumult, as well as the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Just as it is apparent that the events and issues in the book mirror reality, it is also clear that the narrator’s life mirrors Kumar’s in many ways. Kumar hails from Patna, Bihar and had worked in Delhi as a journalist before moving to the US in the 1980s. He is now Professor of English on the Helen D. Lockwood Chair at Vassar College. The book’s narrator is originally from a small town in Bihar, an author and journalist, who “teaches literature at a small liberal arts college in upstate New York.” There are so many other parallels that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between author and narrator. This blurring of the lines was intentional. It’s an attempt at one level to introduce an air of non-fiction in the narrative, as if Kumar was reporting from his own life. “At another level the overlap is because I want to mess with my reader’s expectations. I want them to factcheck and question things.” He adds, that if in this small way they become more critical readers, then they may become more sceptical citizens. “And then, you do not treat the real as something that has to be immediately put in a WhatsApp group.”

It’s not surprising that this novel at first seems like autofiction, which simultaneously reads like a memoir and reportage; like Kumar’s other novels, it falls between several genres. The instances of flashbacks set a tone that is both nostalgic and matter of fact. It is again easy to see how boundaries between Satya and Kumar overlap, unless one marks the discrepancies.

Fiction, like lies, can seem authentic if there are certain elements that make the story plausible. This is the case in several of the many disturbing incidents Satya chronicles, most of which did take place in reality. One case, based on real events, is that of Shahid Farooq, a Pakistani student who after 9/11 is forced by US authorities to become an informer of ‘suspicious’ activities. These fictional incidents seem like all too familiar true stories, gaining verisimilitude. But when Satya questions all sides of the same story, doubts appear. In each case, Kumar drew on personal experiences, but his effort has been to write fiction that gets to the heart of truth.

“When we are surrounded by the fiction of fake news, let me create fiction that gets to truth. As my friend the author Geoff Dwyer, says, ‘I like to write stuff that is only an inch from life’—but all the art is in that inch.”

The structure of the book includes many genuine news tweets and newspaper clippings, keeping alive the impression of a sequence of events in the real world. This was an attempt to be inventive with the form of the novel, and present the sense of a novel that belongs to the actual moment. Kumar elaborates, “I’m interacting with people who research news, and I’m trying to do something more modern. At the same time, I am trying to reflect on the modern technologies that surround us.” His writing style in the book also includes efforts to draw upon themes writers from the subcontinent had delved into, and build on them differently. Gesturing to the bookcases behind him, he adds, “My book was a way of asking South Asian writers, such as Yashpal [author of This is Not That Dawn], how do I make the experience meaningful? When you are writing a book, you are also engaging in a dialogue with the books that have come before you.” The book itself, with its purpose and skill in forcing readers to be sceptical while seemingly grounded in reality, is novel in how it pushes all boundaries, more than atoning for its lack of plot.

ALTHOUGH THE BULK of the novel was written during the pandemic, it has been a four-year long project, where, like Satya, Kumar critiqued prevailing propaganda narratives, fact checking and recording in journals and scrapbooks all the news he heard in the first half of 2020.

He shows me a small pale brown notebook, with the number 73 written on the top corner of the cover. “Every day I write 150 words on whatever project I am working on and whatever I hear that I find relevant to my writing. This is a practice I’ve followed for over 10 years.” This is also an exercise that Kumar requires of his students.

Another habit Satya cultivates is the importance he gives to slow news. He notes, “Slow news. I now think of it as a performance. How to perform the news so that it reveals its inner self. Or something like that.” Instead of the pace of fake news, he attempts to use literature as a medium which can put a brake on things and make you a more reflective consumer of the news. Kumar adds his views on the virtue of slow news. “Bad news keeps coming at a furious pace, and the truth, which I discovered while keeping my scrapbooks, is that I forget the name of the man who was killed the previous week.”

It is no coincidence that the protagonist’s name is Satya. The 1998 movie Satya, inspired Kumar to write his first novel. It also led him to discover the actor Manoj Bajpayee. Bajpayee is from a village that is half an hour from Kumar’s own hometown. Kumar phoned film director Shyam Benegal and asked for Bajpayee’s number. “My first novel has a character like Manoj in it. The idea of a man from a small town in the Hindi hinterland, then coming to this country, led to some part of this character appearing in several of my books.” This was also a way of connecting some of his books and is a tribute to Bajpayee.

Presently Kumar is writing a book on the second wave. Two of his previous books A Matter of Rats, a biographical account of the city of Patna, and Immigrant, Montana, centred on a small-town boy from Bihar trying to find his identity in the US, could be said to reflect certain stages in his life;

A Time Outside this Time reflects another. A Matter of Rats was a quick nonfiction report on his roots. “It was an exciting project for me about my hometown. It was a summer where I went back to my village in Champaran interviewing people and watching people catch rats, which Patna is infused with. Immigrant, Montana was trying to infuse in the immigrant experience novel, an exuberance that had been lacking.” Kumar’s new book also reflects a point in his life. “There is a pandemic of fake news sweeping [the world]. In answering the question in what form literature must take in responding to this issue, and coming up with certain strategies, I feel my novel is a serious attempt at a serious response to these questions.”

Like Satya, Kumar feels he doesn’t belong to either India or the United States. He values his time in the US, and the benefits of its education system. Although, as he says, “So many in America won’t think of my characters as inhabiting the same human landscape they do.” Readers in India may also feel writers abroad won’t have the same attachment and understanding of India, a thought which rankles him. He declares, however, “I belong in the space of imagination. My real alliance is to language, and in finding language and putting to the page certain things that evoke feelings in people reading it in this country or the country of my birth. All my stories are from India.” Kumar adds, “Subcontinent writers often feel they are in a no man’s land. I feel I belong in the land called language, that is what the writer’s credo should be.”

Satya in the book, like Kumar in reality, feels he cannot imagine a time outside this time, but he still sees hope in the young people at the helm of much-needed movements such as Black Lives Matter. Taking heart at the peaceful protests during the Black Lives Matter movement, he says, “I liked that a protest was taking place...

There were so many young people, all of them marching and singing and dancing…I was glad.” Both Satya and Kumar understand that the youth are at the helm of such movements and can prompt change.