A Courtesan’s Tale

In Saba Dewan’s 2009 documentary The Other Song, the framing device for the narrative is a 1935 gramophone recording of ‘Phool Gendwa Na Maaro’ by Rasoolan Bai (1902-1974), a former tawaif (courtesan), a Hindustani classical singer from the Banaras gharana and a thumri virtuoso. The popular, much-covered version of the song goes “Phool gendwa na maaro/ laagat karejwa mein chot” which roughly translates to “Don’t throw flowers at me/ My heart is wounded”. But on the version that Dewan was looking for, the word karejwa is replaced with jobanwa; literally, ‘youth’, but here, this euphemistic word means ‘breasts’. Somewhere along the line, as tawaif histories were either erased or sanitised in independent India, their songs, too, were cleansed of erotic connotations—Dewan’s achievement with The Other Song was to map these developments.

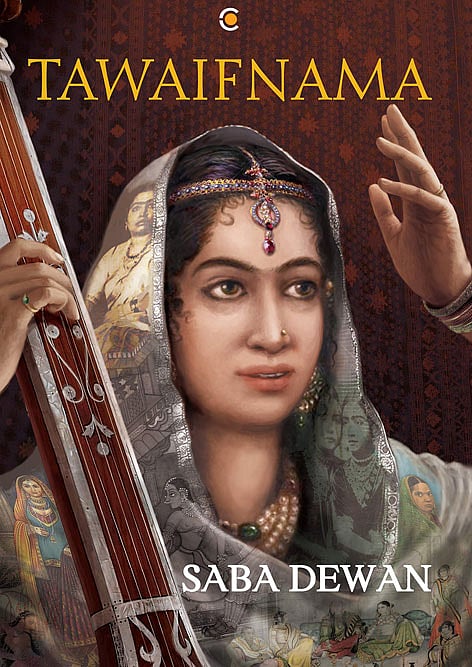

With her recent book Tawaifnama, Dewan has now shown us how these developments typify India turning its back on its secular, composite culture. This is easily one of the most ambitious new nonfiction books to come out of the subcontinent, formally speaking. It follows the family tree of 19th century tawaif Dharmman Bibi—the first of three generations of women in her family who became brilliant performers (throughout the book, Dewan speaks to an ex-courtesan, an unnamed modern-day descendant of Dharmman Bibi). Tawaifnama has elements of straight-up reportage, history and ethnography, all interspersed with novelistic bits that make the narrative all the more compelling. What begins as a fly-on-the-wall journalistic exercise ends up becoming, arguably, an oblique history of gender, sexuality, secularism and ‘propriety’ in India over the past 150-odd years.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Over and above its scholarly qualities, Dewan’s book also has a very enjoyable episodic quality to it. Its anecdotes are always entertaining, whether they feature relatively little-known figures like Sadabahar, Dharmmman Bai’s daughter and a golden-hearted tawaif blessed by an aghori baba, or more mainstream figures like the famous singer/actor Begum Akhtar, who had appeared in Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar.

Take the story of Teema, for example, a courtesan who fell in love with Daya Singh, a landholding Rajput from Shahabad, a Bhojpuri-speaking region in Bihar. Daya Singh’s brother Veer Bahadur was inspired by Kunwar Singh and other Rajput leaders in Bihar who had fought their British overlords. United as they were in their hatred of the British, the two brothers had divergent views when it came to Muslims—Dewan does a wonderful job of showing how Veer Bahadur, aided and abetted by his bigoted Arya Samaj gurus, developed into a misguided, dangerous man with an irrational hatred of Islam. After Teema foils his propagandist attempts at ridding the tawaif colony of ‘vice’, he develops a grudge against her, which is solidified when his brother Daya wants Teema to accompany him to Ranchi, his new home (Daya’s wife, meanwhile, is ordered to stay back in Shahabad). With the Arya Samaj in his corner and other self-proclaimed Hindu leaders by his side, Bahadur decides to use the issue of beef consumption as an excuse to target the Muslim-majority tawaif colonies of Shahabad.

Dewan writes, ‘That his brother had kept a lowly Muslim prostitute as a mistress was bad enough; to sanctify that relationship by taking her along to keep house as a wife was reprehensible. (…) If allowed to grow unchallenged, there was no saying what impact this intimacy might have on the patriarch’s duties and responsibilities towards his own flesh and blood.’

The life of the mid-20th century tawaif, in particular, is a treasure trove for historians, sociologists and students from several other disciplines—Tawaifnama proves this all over again. Indeed, at the book’s Delhi launch, Dewan was joined by Veena Talwar Oldenburg, perhaps the single most prolific and widely-cited tawaif scholar in the world. It’s a pity that even today the likes of Talwar and Dewan have to fight off legions of puritanical Veer Bahadurs before their stories achieve the wide audience that they so richly deserve.