Inconvenient Martyr

That a headscarf can cost someone her life is disturbing enough. That the world media looked the other way is worse

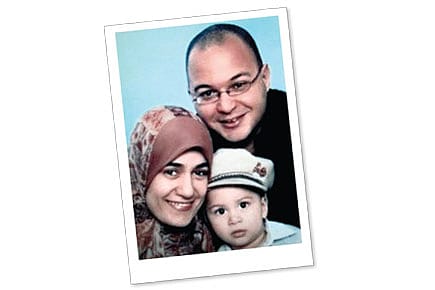

She was not in the wrong place at the wrong time. She was just a mother who had taken her child to a playground, as parents usually do. That's where a quarrel broke out between this 32-year-old mother, Marwa el-Sherbini, and a 28-year-old male, Alex W, over who would play on the swings first, her son or his niece. Alex W tried to tear off Marwa's headscarf, calling her an "Islamic terrorist" and "whore".

She sought recourse to the law, filing charges against Alex W (whose full identity remains concealed). Thus it was that she found herself in a courtroom in Dresden, Germany, on 1 July 2009, at the right place at the right time, offering her testimony. This time, the whole court was witness; Alex W, the accused, strode up to the plaintiff, Marwa el-Sherbini, and stabbed her 18 times.

Marwa died. She was three months pregnant. The police compounded the tragedy. Arriving on the scene after her knifing, the police opened fire, shooting her husband who had rushed to her aid in the courtroom, apparently on the assumption that he was her attacker. Little Mustafa watched both his parents fall to the floor.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Marwa el-Sherbini's murder in Germany ought to have made global headlines. She was young, pregnant, a qualified scientist and beautiful. The newsworthiness was obvious. Above all, she was an innocent mother—in a headscarf. But it didn't. It took three days for Marwa's slaughter to get a news mention, that too on the back pages of German dailies. The news has finally gotten out, and, in this era of globalisation, gone around the world. On reliable reports, Alex W heckled Marwa in the courtroom, saying, "Do you have a right to be in Germany at all? When the NPD (a neo-Nazi right-wing group) comes to power, there'll be an end to that. I voted NPD."

Marwa did not conform to the cardboard cutout of the 'Muslim Woman'. She was a spry athlete, popular in Egypt for being a national-level handball player. She went on to qualify as a pharmacist. She was liberated enough to retain her own surname and not assume that of her husband, Elwy Okaz, a research scientist at the prestigious Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden. She happened to wear a headscarf as well.

Even in Europe, there would have been enough people interested in her case. The headscarf, seen as a milder version of the head-to-toe burkha, has been a raging issue of cultural conformity and/or women's rights, depending on how it's framed. And after France, Germany has the most Muslims—4 million—in Europe. Yet, the Associated Press report appeared unusually late.

The media silence prompted civil rights group Cojep International to issue a release condemning the attack and calling on Angela Merkel's government to speak up against this hate crime. But it was in Egypt, mostly, that public sympathy was aroused. When Marwa's coffin arrived in Cairo and reached her hometown Alexandria, thousands poured onto the streets to mourn her. Says Jack Shenker, who reported this for The Guardian (among the few Western publications, besides The New York Times and Time, to cover this case), "Egyptian society has been turning more visibly Islamic in recent decades, with more women wearing the headscarf. Many saw Marwa's murder as an attack on Islam and consequently an attack on Egypt." Joseph Mayton, Cairo-based editor of Bikya Masr, a news website, says, "Most Egyptians look to Europe as a place to go for freedom, that's why the killing shocked people."

Some six weeks after her death, Marwa, a woman with dark eyes, a light complexion and a broad smile, has turned into the Martyr of the Headscarf. The fabric is becoming a symbol of assertion, showing up starkly all over Europe, even as colour-coded politics makes a re-appearance with White supremacist groups growing bolder.

Just eight months ago, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe said, 'One of the greatest challenges to human rights is the rise of… racism and xenophobia against Muslims.' Last year's key finding by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights was that racist crime and discrimination against Muslims was grossly under-reported.

We have all seen media reports, images and YouTube clips of Muslim women suffering the oppression of patriarchal Islamists—think of Neda Agha Soltan who was shot dead in Tehran, or the flinch-inducing cries of the woman being whipped in Swat. How has the Headscarf Martyr come to escape wider public notice? "Marwa does not fit the dominant narrative that Islam is bad to women," says Mallika Dutt, executive director, Breakthrough, an organisation trying to foster a culture of respect for human rights. Aijaz Ilmi, who is on the editorial board of Daily Siyasat, an Urdu paper published from Kanpur, was in the Cairo office of Al Ahram, a leading Egyptian weekly, when the story broke. It sent shock waves through the newsroom, he recalls, calling it "a prime case of bigotry, racism and xenophobia that was near blacked out in the main echelons of the Western world".

It was only after widespread Egyptian street protests and media outrage that the story filtered back to the German press. Oddly enough, when Iran's President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called for international condemnation, Germany clamped down on press coverage to prevent racial rioting. A diplomatic statement issued by the Egyptian Embassy in Germany, meanwhile, has called it a 'criminal individual incident'. Germany's response so far has been to tighten armed security in courtrooms, that's all.

To those with a broader attention span, the echoes from the past are worrisome. "Muslims are becoming Europe's new Jews," says Bashy Quraishy, who chairs the European Jewish Muslim Co-operation Platform in Belgium. They've become targets of the Far Right, accused of spreading terrorism and violence, being backward and refusing to integrate with Western culture. Senior Arab journalist Dr Waiel Awwad, based in India since 1998, was in Syria and Iran at the time, monitoring the case. "There was widespread anger and anguish, though Iran was at the peak of a domestic crisis, women and human rights activists demonstrated before the German embassy in Tehran." In Pakistan, there was criticism from the liberal corner as well as radical clerics. "But the liberals are busy addressing the plight of their own minorities, such as the recent assault on Christians, to sustain such a campaign," says Jawed Naqvi, a Delhi-based columnist for Dawn.

"This human story was made for global media coverage, which it didn't get," says Ilmi. "I think there is cultivated ignorance. We are being shepherded in a direction where we are cut off from any alternative view," says Naqvi. Shenker calls it a sign of "pack journalism". Adds Awwad, "If we ask about Neda, we must ask about Marwa."

As for India's own ostriches, a few reminders. The headscarf, turban and bindi have all been targeted. This June, French Prime Minister Nicolas Sarkozy issued a controversial statement calling the hijab "oppressive". Many supposedly erudite European opinion makers agreed. In the US, an African-American Harvard professor's arrest, though suspiciously motivated, is being brushed aside as due process. Even Australia is bristling with racism. Some 1,500 Indian students have been attacked on Australian and American campuses since last year. This violence is different from that of the Dotbusters, the New Jersey gangs who singled out Indian women by their bindi in the late 1980s. In today's shrinking world economy, "qualified Indians (and outsiders) are being seen as job-snatchers", says Harsh Dobhal, editor of Combat Law and a West Asia expert. "Marwa's scarf was no threat to public interest," he says.

"Unfortunately the writing on Marwa has died down," says Mayton, "It is all but a moment in history. It is gone, as are conversations about racism in Egypt and in Europe." On August 22, the Bikya Masr site reported that the public prosecutor's office will be charging Alex W with the murder of Marwa and the attempted murder of Elwy Ali Okaz.

In Dresden, whenever Mustafa and Elwy find the courage to venture out again, the little boy and his father might regain one of life's greatest pleasures. The joyous freedom to swing your child in the park and hear him call, "Higher, higher, all the way to the sky!"