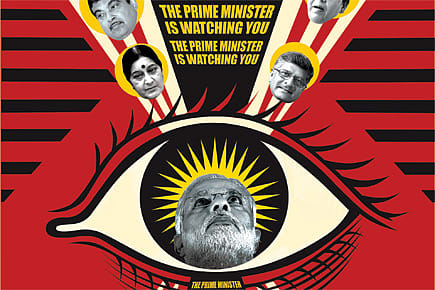

The Prime Minister is watching you

Do it or be damned. After closely watching Modi at work, we deconstruct the big message from the first ten days of the Prime Minister

Late on Monday evening, 2 June, first-timer Nirmala Sitharaman, Minister of State for Commerce and Industry, tweeted, 'It was inspirational'. She had just emerged from a marathon three-hour meeting of the Union Council of Ministers, the first one chaired by Narendra Modi as India's Prime Minister, at South Block.

It was well past 9 pm. The tweet itself was a radical departure from the norm at such meetings that were held over the past 10 years under the stewardship of Dr Manmohan Singh.

Tweeters are an insomniac lot. But at that hour, one would have imagined the traffic would be slow. Not so. Sitharaman was deluged by comments and congratulatory messages. Among them were many that advised her to take that inspiration and use it to implement the mandate of the people. Her followers urged Sitharaman to divulge exactly what the Prime Minister said. Social media, clearly, has been tracking every move of the NDA Government from day one.

The public eagerness to hear exactly what inspirational pep talk Prime Minister Modi had delivered to the Class of 2014 was understandable. There was none of the media cirque du soleil that preceded such meetings in the past. Under the UPA regime, it was only on rare occasions that the entire Council of Union Ministers met, such as dates that marked anniversaries of the Government. On that Monday evening, though, the media was banned from even the forecourt of South Block, clearly sending out a 'Do Not Disturb' signal that would be a norm in the future.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Quite early into his term, Modi was clearly indicating that there was going to be a radical change in the way the Government worked from now on. Both ethically and operationally. Within the four walls of the conference hall at South Block where his team of ministers waited, Prime Minister Modi dispensed with the old frills and dived straight into outlining the brief for the strategy meeting after introductions. The conference, he emphasised, was meant to formulate strategies that would deliver on the hopes of India.

The context was clear to those in the hall. They had all come after having done their homework. Several hours before summoning his team, Modi had not only held one-on-one meetings with all his senior ministers, but given them a broad but non-negotiable framework for achieving goals of governance. The 10-point agenda included plans to increase investment, complete infrastructure projects in a time-bound manner in order to prevent cost overruns, and also instill accountability among bureaucrats for them to respect deadlines and project outlays. 'Set a timeframe, stick to it,' was the core message.

Outside, as the sun went down, the massive pillars delineating the majestic façade of South Block on Raisina Hill added to the gravitas.

Past Prime Ministers had, by and large, been working out of their official residence at 7 Race Course Road, even forcing the authorities to put up permanent fixtures for the media outside. Cabinet meetings were usually held at Panchvati in the PMH complex.

The venue for Modi's conference was deliberately chosen in order to set the tone: official business should be conducted strictly at ministerial offices only and not at residences. Clean front offices and a strict barring of all gifts and presents would magnify the message that this was a government that meant business and that decisions would not be influenced by lobbyists, friends and relatives.

There was another sub-text to the choice of venue. Ministers were being told that they should keep their family members out of their staff. One senior UPA minister from UP, whose wife is understood to have used his name and position constantly to beef up a social welfare organisation, was later accused of siphoning off funds meant for the physically challenged. Another UPA minister's brother managed to wrangle a coal mine jointly in his name and that of his brother. Yet another minister, in charge of coal, had a mine allotted to a member of his larger clan who had the same name as his. Again, just one day after the meeting of the Union Council of Ministers, K Chandrasekhara Rao, the first Chief Minister of the newly-formed Telangana state, won dubious fame for appointing his family and friends to manage all key portfolios. Modi would have none of this.

The Home Ministry has already distributed copies of the code of conduct to be followed by ministers, a review of which would be done in two months. The top three in Modi's Cabinet—Rajnath Singh, Arun Jaitley and Sushma Swaraj— proceeded to reinforce the ethical standards expected of government business by their boss. Ministers were told that they should speak only for their departments. They have, however, the right to silence.

Following the leitmotif running through Modi's own speech, they understood that graduating from being members of the opposition party to ministers in the ruling party involved fundamental changes in attitude. Criticism had to be taken constructively in order to fine- tune key strategies. The big four also emphasised that there was no place for arrogance in the new regime. It was hubris that had driven a wedge between the UPA and India. The new regime, they were clear, was determined to learn from the sins of its predecessor.

Turf wars would be discouraged. According to some conservative estimates, Jairam Ramesh, the UPA's environment minister, had single-handedly shaved 2.5 per cent off the country's GDP, through his 'Go/No-go' proposal. To avoid such a situation, ministers overseeing departments that needed to operate in synergy with others were asked to constantly interact on crucial issues and coordinate their actions. As a good student, Power Minister Piyush Goyal immediately held a separate meeting with his Environment counterpart, Prakash Javadekar, to sort out the contentious issue of green clearances to industries.

The meeting broke only after Modi was fully convinced that he had been able to drive home his message. In his concluding remarks, he deftly tied the key issue of job creation to both decision-making by ministers and their implementation. "Tone up the administration and enforce accountability from top down. Your decisions should touch the lives of people personally," Modi emphasised. He also indicated that he plans to rightsize the Government as early as possible. Referring to the 600 odd personal staff of ministers who have stayed in their posts after the power shift, a senior minister ordered that their antecedents be verified before they're allowed to continue. Days prior to his oath-taking, Modi had told Open, "I plan to break the cabals and cliques that control New Delhi." On Monday evening, he set the deadline.

The end of the meeting was, however, just the beginning of the new work ethic for Modi's team. The effect of the Prime Minister's address was apparent immediately. Most ministers refused to divulge any details. Ram Vilas Paswan, who has worked with five prime ministers, said that he had never seen such interaction in the Council of Ministers. The zipped lips that most ministers sported was also in sync with the new sobriety instilled. Strict instructions were issued not to rush to the media with word of the interaction. Consequently, most of the attendees switched off their mobile phones or were unwilling to share details of the deliberations.

Modi wanted to make it clear: there is only one master in the house and he brooks no indiscipline. This was a definitive departure from the UPA, under which Cabinet meetings actually nurtured an environment of ill discipline. Ministers such as Jairam Ramesh and Jayanti Natarajan—both of whom were environment ministers at different points— could actually indulge in the very "solo flights" that Modi warned his ministers against and challenge even the head of their team on policy positions. Ministers would stroll in after Manmohan Singh himself arrived at Cabinet meetings.

The ministerial meeting took place two days before Modi's decision to scrap all Groups of Ministers (GoMs), a move that marked a new decisiveness. The setting up of GoMs was a ruse employed by the UPA to put critical but contentious policy decisions in the deep freeze. On paper, these groups were set up to deal with multi-disciplinary decisions, but ended up reinforcing the regime's paralysis, rendering it unable to make quick and timely judgements on crucial issues.

During the UPA regime, groups headed by senior ministers such as P Chidambaram, AK Antony and Sharad Pawar ducked decisions on key issues either because they could not find the time to attend meetings or because they deliberately avoided politically touchy decisions. Pawar, for instance, was known to routinely adopt this tactic and then claim that he had not attended the relevant GoM and could not be blamed. The groups also allowed for lobbying by vested interests and postponing of decisions unfavourable to them.

That explains the Modi Government's press release which contends that abolishing these already defunct bodies would increase the accountability of ministers and expedite decision-making.

GoMs and EGoMs—'empowered' GoMs—under senior ministers institutionalised the weakening of the PMO under Manmohan Singh. Modi would not allow such a scenario. He made it plain that should situations arise where relevant ministries were unable to resolve issues, the Cabinet Secretariat and the PMO would facilitate interaction between them.

The meeting with ministers was quickly followed up by a meeting with secretaries. The message was not lost on Babudom that the new regime would put a premium on accountability. Social sector projects, too, would be monitored stringently to ensure that only the eligible would benefit.

The buzz around this meeting had already begun days earlier, with news that the PM had asked secretaries of different departments to come up with 10-minute slide shows outlining their priorities. At the Wednesday meeting with top bureaucrats, there was only one message: work without fear, I am here for you, and get through to me directly whenever there is a problem.

That the new Prime Minister wanted quick action was evident immediately after the victory. In the appointment of Ajit Doval as National Security Advisor, he refused to allow Delhi's policy wonks to sway his belief that the former Intelligence Bureau chief was the best man for the job. The wonks had argued that the position has a large foreign policy component to it and should not be vested with a so-called 'policeman'. Modi stuck to his decision. Doval will now preside over the IB (though it technically reports to Home Minister Rajnath Singh) and RAW.

Moreover, as the head of the executive council of the Nuclear Command Authority, Doval will also be the custodian of India's nuclear codes. This gives him an international profile. Meanwhile, Modi has already shown—in the face of scepticism—that he can hold his own in the arena of foreign affairs by inviting SAARC leaders for his swearing- in ceremony.

Soon after taking charge at South Block, Modi convened a meeting of BJP general secretaries. Even 11 Ashoka Road would now come under the domain of the Prime Minister. He will control the Church as well as State.

Modi told party leaders that he would hold at least one meeting a month to ensure that the party is in complete harmony with the Government. "The party should not have the feeling that it has no say in the Government. They were the workers and leaders who made the mandate possible." Modi informed party leaders that his ministers would interact with them at regular intervals.

Those in the know maintain that some senior party leaders were not accommodated in the Government despite their claims because Modi had received specific information on their collection of funds for electioneering from industrialists. Some of these men were hot favourites of the media during the Government formation process.

A new prime ministerial routine exemplifies Modi's style. Earlier PMs would scurry straight past other South Block offices to their own corner room. After taking charge, Modi has made it a point to survey every little section. "He makes one round of South Block every day," a PMO official tells Open.

The chief executive of India worked hard to be where he is today. He works harder to remain there undiminished.