Bihar: Land without Justice

On 23 July, a motley group of around 200 Mallahs gathered at the house of Ashok Sahni in Vijay Chhapra, on the outskirts of Muzaffarpur in Bihar. The occasion: taking stock of preparations for the Nishad Rally to be held at Gandhi Maidan in the state capital of Patna a couple of days later. The mood was bullish and the dinner sumptuous. Mukesh Sahni, a Darbhanga resident who made his fortune in Mumbai but is now focusing on the political empowerment of fellow Nishads, is part of the planned soiree. "We Nishads have been officially categorised as OBCs. But we have nonetheless not been empowered sufficiently, either by politics or State policy. We have little political muscle, and our children find themselves at a disadvantage when it comes to securing places in the government or in educational institutions," he says. In the run-up to Bihar's upcoming Assembly polls, Mukesh Sahni plans to churn Bihar's caste cauldron to ensure that the social matrix gets configured to weigh in on the side of Nishads. Sahni plans to lead a campaign for the 'real empowerment' of his community by exploiting the demands of competitive caste politics in his state.

"We will demand to be included by the government in the Mahadalit category," he asserts. If he clinches that for his community through political pressure—Bihar's Nishads, categorised among the less advantaged backward classes or MBCs—it would put them officially on par with Scheduled Caste (SC) groups, traditionally far lower in the social pecking order, that are currently eligible for affirmative action schemes in government jobs and education. As part of the larger grouping of MBCs (Most Backward Castes), which comprise a whopping 23 per cent of the state's overall vote, Nishads have proportionately a far lower representation in the state Assembly than even Chief Minister Nitish Kumar's caste group of Kurmis although their population is twice the latter's in Bihar. In the thick of the prevailing competitive caste politics, Sahni plans to effectively leverage his community's vote share to boost its political and social advantages.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The upcoming Bihar Assembly election is perceived as the most politically and strategically crucial after last year's General Election in which the NDA, led by the BJP, garnered a significant chunk of MBC support. With close to 130 different caste groupings, the MBC vote bank has by and large been a disparate, non-cohesive one, posing a key challenge to any political party trying to woo it in Bihar. Given its gains among MBCs in the General Election, the BJP is laying plenty of emphasis on them in the caste calculus of its electoral strategy.

Bihar's MBCs, who are now well aware of their growing electoral importance, have held a spate of caste-based rallies in Patna's Sri Krishna Memorial Hall and Rabindra Sadan, aiming to leverage their vote share to obtain more seats from political parties. The meetings were meant to highlight their legitimate claims to a bigger slice of the political pie and linked policy benefits. Among the caste groups crowding the halls were Telis, Chowrasias, Noniyas, Dangis, Kanus, Dhanuks, Chandravanshis and Hajjams, besides Nishads.

As the polls draw closer, the clamour for a re-configuration in the state reservations list, too, grows louder. In politically sensitive Bihar, finding the right caste matrix to reconfigure the social justice message has for long been viewed as imperative for political parties to capture and retain power. Traditional political issues and tactics, even development, have tended to have little impact on the electorate if delinked from caste-based social engineering, something that both Nitish Kumar and the BJP are well aware of.

In a bid to woo a section of these vocal groupings away from the BJP, Nitish Kumar recently reclassified Telis and Chowrasias as MBCs, moving them downward from the OBC category. He followed that up with moving Badais and Dangis to the MBC list. In addition, he reclassified Tantis, Chaupals and Khataves (Julaha sub-castes) as SC and Maal Paharis as STs. "If this sounds like a cynical exploitation of vote banks, in the name of social justice, by political leadership to remain in power, it is. The Yadav and non-Yadav OBC vote shares account for 15 per cent each and had 38 and 56 representatives in the Assembly, respectively. On the contrary, despite accounting for 23 per cent of the vote share, the MBCs have only 13 MLAs (barely 5 per cent of the 243-member house)," says a Patna- based BJP leader.

The use of social justice slogans for political gains goes back to Lalu Prasad Yadav's era, even while the national mainstream was hailing him as a 'social justice hero' who had effected a transfer of power to OBCs from upper castes in Bihar after several decades. Not only were there tensions between Yadavs and Dalits in constituencies where the latter were numerically dominant, with many Dalits not even allowed to vote, but Lalu's political exploitation of Muslims also came into question. A large number of MBCs also tagged along under the banner of social justice when Lalu forged ahead with his 'Bhura baal saaf karo' slogan (exhorting followers to finish off upper castes politically). Besides, it helped him in the period between 1990 and 2005, when Muslims, who constitute 16 per cent of the state's vote, stayed politically loyal to him. But as early as in July 1994, Syed Shahabuddin had exploded the myth of social justice for minorities in his journal, Muslim India. Listing a number of grievances—including a failure to list Bhatiyas as an OBC community as promised and gradually dismissing a separate budget for the department of minority welfare and shutting down a commission of inquiry probing the Bhagalpur riots of 1989— Shahabuddin accused Lalu of treating Muslims like 'political hostages' who 'must accept humiliation and terror' based on the TINA factor('There is No Alternative'). 'For Lalu Yadav, who swears by the Mandal Commission— social justice means the substitution of Bhumihar-Rajput Raj by Yadav Raj,' he wrote.

Socialist guru Dr Ram Manohar Lohia had warned that a neo-elite among backwards could turn out to be more feudal than the upper castes they supplanted in the power matrix. He had said that the cartelisation of the upper OBC leadership would get deeply entrenched, making it that much more difficult for the lower classes to oust them in the power struggle. "Even today, whatever is demanded in the name of 60 per cent reservation has actually remained a preserve of a handful, of a Backward caste elite. Lohia had maintained that women of all castes should be part of this category since they suffer deprivation. But leaders belonging to the OBC elite have been flaunting Lohia's slogan of 'Samajwadiyon ne baandhi gaanth, pichhde pawein sau mein saath' (Socialists have resolved to get 60 per cent reservation for OBCs) to their benefit alone. Notwithstanding Nitish Kumar's much vaunted efforts to champion their political rights, the representation of MBCs as a whole in legislatures remains abysmally low compared with their numerical strength. This is how social justice with only reservations as an effective tool has been meted out to underprivileged castes by the heroes of the social justice movement, including Lalu Yadav and Nitish Kumar," says Rajkumar of Chaurasia Samaj.

The dominance of upper castes in Bihar politics in the initial decades of India's independence declined over time. The elite among the Other Backward Castes emerged winners, replacing Brahmins, Bhumihars and Rajputs. In the political churn that swept the state in the late 80s and early 90s, Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris were the key gainers, leading to the assertion of neo-Brahminism, especially in the forced suppression of real social justice for lesser social groupings such as MBCs. Despite their numerical strength, however, the community was not able to effect any change in political power equations to its benefit, or gain allowances from the upper OBC triumvirate like they did from upper castes. "To some extent, this was inevitable. It is true in the case of the freedom struggle too. Since upper castes were more educated and got exposed to liberalism and ideas like representational democracy early, they were the first to hit the street. And when we gained freedom, they monopolised the gains of regime change," says a political analyst.

What is not comprehensible, adds the analyst, is the approach of elite OBCs. Having been at the receiving end of various types of monopolistic tendencies, they were expected to behave differently once empowered. Yet, they are now as aggrandising as upper castes. Lohia has been proven correct. The leaders among Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris, according to their rivals, represent a regressive political cartel.

One reason has been that as the upper OBC triumvirate ascended to power, there was also an aggregation of sub- castes under the umbrella of each of these castes, helping a political leader like Lalu Prasad (from the relatively lowly Gadaria community of Yadavs) rise as an emblem of Yadav political prowess in the state. In earlier days, a Yadav notable from Madhepura—the Vatican of Yadavs— would not have accepted the leadership of Lalu Prasad.

The prolonged socio-political debility of MBCs, despite their substantial vote share, and their inability to grab political power and benefits from upper OBCs was primarily due to their lack of cohesion as a political force. In contrast, the sub-castes among the upper OBC triumvirate were bound together by common rituals and practices, facilitating a sense of 'biradari' or brotherhood that socially enables the sharing of benefits within. Yadav sub- castes had Krishna worship as their historical binding factor, for example, while Kurmis claimed a common descent from the Maratha ruler Chhatrapati Shivaji. This 'biradari' was lacking among the various MBC sub- groups, numbering over 120. Another reason was the entrenched social dominance of Yadavs in Bihari society (even if the caste had not reached its zenith of political power under Lalu), which effectively railroaded even the icon of social justice, Karpoori Thakur (of the Nai caste) in the 70s into appointing Rajeshwar Lal, a Yadav, as police chief despite his apprehensions.

Unlike the MBCs, Dalits, who comprise around 18.5 per cent of Bihar's overall vote, also made gains from the caste consolidation of the 90s across north India, in tandem with the upper OBCs gaining political clout. Despite battles of attrition with the latter, Dalits were able to shape the contours of identity politics under leaders such as Ram Vilas Paswan. In the 2014 General Election, a substantial number of them voted for the NDA, and with an enthusiasm unseen even during the Ram Janmabhoomi movement of the early 1990s.

The biggest obstruction in politics that the numerically strong MBCs faced was their internal diversity, which made it difficult for them to unite on a common theme or political platform. Mostly artisan communities, they were not 'untouchables' in the traditional Hindu caste hierarchy. But neither were they land owners, which resulted in their migration to cities for survival over the past few decades. In the traditional setting, MBCs depended for livelihood on the upper caste families around whose homes they settled to provide them services of one sort or another.

The stature of the MBCs has not improved much from the days of the Jajmani system, under which backward castes were paid a fee for services offered to upper castes. Unlike Yadavs and Kurmis who were traditionally sharecroppers, MBCs largely remain socially backward and politically unempowered. MBCs, in that sense, have not benefited from the social progress that ensured the rise of elite OBCs like Yadavs.

The only caste among MBCs that has managed to break out of the political morass is that of Nishads. This has led to a churn within the caste in recent years. The community now has a representation of two members in the Lok Sabha. While Nitish Kumar has been taking credit for extending the process of empowerment by resorting to reservations for MBCs in panchayats and other elected local bodies and institutions, his motivations have come under scrutiny since the JD-U leader has used quotas as a political tactic to buttress his support base and cultivate new constituencies beyond his own community of Kurmis. While the extension of reservations to MBCs is a step forward, Nitish Kumar has been dubbed a 'reluctant reformer' as he stopped short of extending these privileges of affirmation action to the state assembly. In 2005, after his elevation as Bihar's Chief Minister, he sought to emulate the political strategy of his rival Lalu Prasad who had used an M-Y vote formula—of Muslims and Yadavs—to his advantage. "Nitish Kumar was up against rival Lalu Yadav who was sitting on a pile of votes. For him, the MBC move was just a tactic. His own Kurmis were small in numbers and he never trusted upper castes even when he was in alliance with the BJP (he did not give a ticket to a single Brahmin candidate in 2009 and justified it by saying that Brahmins are in the BJP's quota). He had to find pockets of support elsewhere, and hence the attempt to woo the MBCs," admits a JD-U leader who does not wish to be named.

Had Nitish Kumar taken affirmative action right up to the Assembly, he would have acquired the political authorship of this move, as this large group of voters would have stayed with him. This was one of the calculations behind his gambit to split with the BJP. He had hoped that MBCs, as also Muslims who did not want a government headed by Modi, would see his electoral project through.

In the last General Election, the BJP's appeal to OBC voters in Bihar that one of their own, Modi, ought to be India's Prime Minister, had worked well to the party's advantage. While Nitish Kumar's calculation that ending his party's ties with the BJP would make him the state's sole beneficiary of Muslim votes looked good on paper, it did not work out that way. Instead, a consolidation of upper caste, MBC and Dalit votes in NDA's favour helped Modi trounce his rivals. The new social umbrella that the BJP forged—upper castes, OBCs, MBCs and a sizeable section of Dalits— gave the party a lethal support base. The Modi typhoon that swept away BJP's rivals in the Hindi heartland in 2014 also offers lessons for those who base their political calculus on the power of the so-called 'Muslim veto'.

Today, despite Nitish Kumar's alliance with the numerically preponderant and politically powerful Yadav leadership, the reality on the ground is one of mutual attrition. There are inherent contradictions in the RJD-JD-U caste arithmetic that BJP President Amit Shah plans to take advantage of. And the MBC vote is among the most prominent ones up for the grabs in the coming elections. The half-hearted 'empowerment' of MBCs by Nitish Kumar has led to resentment in the community, leaving room for the BJP to step in. Ahead of the rest in co-opting the now gung-ho MBCs, the BJP has already reached out to powerful MBC leaders. The BJP has not shied away from caste-based conferences and rallies including those organised by its core votebank of upper castes such as Brahmins and Rajputs. It was evident when Shah launched his election campaign in the state with a rally in Patna in the memory of former Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur. Besides, state BJP leaders recently celebrated the 2,320th birth anniversary of the great Mauryan King Ashoka, who, they said, belonged to the backward Kushwaha caste. Nitish may end up having to pay a heavy electoral price for leaving the state's MBCs in the half-way house of political empowerment.

In a recent article, political scientist Yogendra Yadav detailed how the politics and policies of social justice had degenerated in Bihar: 'Social justice has turned into a thin foil that can be used to wrap virtually any substance.' By relying solely on reservation to distribute social justice, the leaders of the movement ended up reinforcing the very caste-based injustices that they sought to rid society of, leading to the stagnation, fragmentation and subversion of policies of social justice, he argued.

These mounting fallacies of social justice politics will play out in Bihar's Assembly polls, and the stage is likely to be littered with the wreckage of backward elitism that has reigned in the state for so long. The Most Backward Castes smell blood.

THE CASTE-AWAYS: A brief history of caste politics in Bihar

– The dominance of upper castes in Bihar politics in the initial decades of India's independence has declined over time.

– In the process, elites among the other backward castes have emerged winners, replacing the dominance of Brahmins, Bhumihars, Rajputs, Kayasths and so on.

– Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris were the key gainers of the political churn that swept the state, along with the rest of north India, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

– The run-up to the emergence of the caste supremacy of the abovementioned groups also saw an aggregation of sub-castes under the umbrella of each of these castes.

– Which explains how an unlikely hero, Lalu Prasad, who belongs to a sub-caste among Yadavs considered lowly within the community, Gadaria, rose to epitomise the political prowess of Yadavs in the state.

– What bound various sub-communities were common rituals and practices. While Yadav sub-castes had Krishna worship as a historical binding factor, Kurmis took pride in being the descendants of Maratha warlord Chhatrapati Shivaji.

– Dalits, who constitute some 18.5 per cent of the state's population, were also beneficiaries of a caste consolidation seen in the 1990s and later across north India.

– The rest of the castes, referred to as Most Backward Castes (MBCs), comprised a sizeable chunk of the population: 23 per cent.

– However, there could be no aggregation among individual social entities thanks to various castes within this group remaining disparate, sharing no common rituals or descent.

– These MBCs were so diverse that there was hardly any political current or undercurrent to unite these 150-odd castes of Bihar that have not found adequate political representation in either the state Assembly or Parliament.

– MBCs, mostly artisanal communities, were not 'untouchables' in the caste hierarchy, but were not land owners either, which meant that over the past few decades many of them have migrated to nearby cities for survival.

– Once 'settled' around the homes of upper castes on whom the MBCs depended for livelihood, communities such as Kahars (water bearers) and Nais (barbers) hardly had any property of their own.

– Unlike Yadavs and Kurmis who were traditionally share- croppers, MBCs largely remain socially backward and politically unempowered. MBCs, in that sense, have not benefited from the social progress that ensured the rise of elite OBCs like Yadavs into the political limelight.

– Their stature has not improved much from the days of the Jajmani system, in which backward castes were given a fee for the services they offered upper castes.

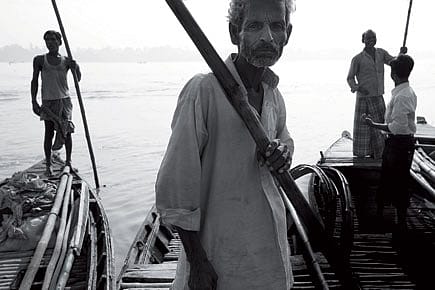

– Lately, the only caste among MBCs that has shown signs of gaining some political clout is that of Nishads (boatmen). There has been a new grouping of various sub-castes of fishermen and boatmen in recent years.

– Nishads, who form 7 per cent of Bihar's population (which is more than the numerical strength of Kurmis who constitute only 4 per cent), have a representation of two members in the current Lok Sabha.

– The representation of MBCs in legislatures and local bodies remains abysmally low compared with their numerical strength notwithstanding Chief Minister's Nitish Kumar's much-vaunted efforts to champion their political rights.