In Hot Pursuit

What it took for a small team of the Mumbai Crime Branch to finally track down the killer of Pallavi Purkayastha in Kashmir

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

18 Oct, 2017

|

18 Oct, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Hotpursuit1.jpg)

ON OCTOBER 10TH, two men entered a construction site in Kashmir Valley’s Sonamarg area, around 80 km from Srinagar. The two had shown up on the premises just a few days earlier along with a contractor working there. Their leader had said they were from a telecom company and wanted to survey land for the installation of mobile towers. Sensing a big opportunity, the other contractors told them they would be happy to show them around.

That day, the two reached the site and walked slowly to a spot where a young man was busy breaking a boulder. There was a ditch behind him; his neck was bent, so he saw the leader only when he stopped in front of him and took his hand in his. He looked to his right and saw the other man now standing between him and the ditch. “Sajjad, you have to come with me,” the leader gently said and then let go of his hand. The man froze.

Yanked up, the man was made to walk, flanked by the two, towards a waiting car parked about 100 metres away with two other men. Once they were all seated and the vehicle was on its way, the leader, sitting next to the driver, turned back and handed an apple to Sajjad. “Eat it,” he said. Sajjad looked at the man and uttered: “Nikam sahib, aap (You, Mr Nikam)?”

On the morning of August 9th, 2012, a 25-year-old woman, Pallavi Purkayastha, who worked as a lawyer with an entertainment company, was found dead in her 16th-floor apartment in Wadala, Mumbai. Her throat was found slit and she had been stabbed 16 times. A national-level swimming champion, Purkayastha’s parents are civil servants; she lived with her partner Avik Sengupta, who she had met at law school. The two were supposed to get married a few months later. The body was discovered by Sengupta at 5 am after he returned from a particularly busy workday.

“Initially, we suspected Sengupta of having committed the crime,” says Inspector Mahesh Tawde of the Mumbai Police. But an analysis of his mobile phone and independent witnesses in his office established his innocence. It is then that the police learnt that a building watchman had been missing since the previous night. He was identified as 22-year-old Sajjad Ahmed Mughal from Kashmir. Upon checking his records with the security agency that hired him, the police were in for a shock: his address was simply mentioned as ‘Lal Chowk, Srinagar’, the city’s main market square.

His phone was switched off. But the Police managed to arrest him at Mumbai Central railway terminus the very next evening. Sajjad was about to board a train to Surat, from where he planned to escape to Kashmir.

Under sustained police interrogation, Sajjad revealed that he had killed Pallavi Purkayastha. He said he would lust after her and had planned to rape and then kill her. For this purpose, he had brought a knife about 15 days prior to the murder. He said he had shared his plan with a fellow watchman, but when he got alarmed, Sajjad told him that he was just joking.

On the night of August 8th, Purkayastha returned home at 11 pm. Realising that her partner would be away for the night, Sajjad tripped the electricity, forcing Purkayastha to call an electrician. Accompanying the electrician to her apartment, Sajjad stole the key to its main door lying on a table in the living room. At about 1 am, Sajjad made his move. Armed with the knife he had obtained, he opened the apartment door and sneaked in.

“She must have fought well,” says Inspector Tawde. “But then her strength began to ebb as he slashed her throat with the knife.” Afterwards, he stabbed her repeatedly, as the case records note, and once he was convinced she had died, he left the apartment and then fled by scaling the wall of the housing block’s compound.

Even as she was slipping away, there are indications that Purkayastha had sought help. A pool of blood outside her apartment suggests that she had tried reaching out to neighbours. It is possible that she rang the doorbell of at least one of them but nobody woke up.

Purkayastha’s brutal murder left her family devastated. Sengupta sank into depression and died of an illness on November 14th, 2013.

On August 9th, 2012, Purkayastha was found dead in her Mumbai apartment. Her throat was found slit and she had been stabbed 16 times. The sessions court found Sajjad guilty but the crime not ‘rarest of the rare’

On October 30, 2012, the Mumbai Crime Branch had filed a 434-page charge-sheet with 40 witnesses. Sajjad’s bloodstained clothes, the knife and forensic analysis established his guilt in the gruesome murder. The sessions court found him guilty, but the judge felt that the crime did not fall in the ‘rarest of the rare’ category, sentencing him to life imprisonment. The judge wrote in her judgment that ‘sixteen times stabbing is cruelty but not extreme cruelty’. In a newspaper column later, the victim’s distraught father, Atanu Purkayastha addressed the judge: ‘Exactly how many times must a victim be stabbed to merit extreme cruelty in your dictionary, Justice Joshi?’ The Maharashtra government also filed an appeal in the Mumbai High Court asking for the punishment to be enhanced to a death sentence.

Sajjad was lodged in Nasik jail.

In February 2016, in a shocking dereliction of duty, Sajjad was set free on parole without any police escorts to meet his supposedly ailing mother. The parole period was set at 30 days. It is not clear what prompted the prison authorities to grant the convict such a long period away from prison, that too without consultation with the Mumbai police.

Investigations revealed later that after he got out, Sajjad worked again as a security guard at an apartment complex in Mumbai’s Andheri area. He changed his name to Imran Sheikh and found employment as a guard at another under-construction building before he left for his village in Uri, Kashmir.

His parole was over, but he did not return.

THREE MONTHS LATER, the Mumbai Police realised that the man they had arrested was absconding. By this time, many in the team that arrested Sajjad in 2012 had shifted elsewhere. The only man left in the team was Inspector Sanjay Nikam, who was instructed by his seniors to pursue the case and nab Sajjad.

A team of Nasik policemen had already visited Sajjad’s village twice. In June, when they went to trace him for the first time, the team came under attack from local residents and the Jammu & Kashmir Police had to send a group to rescue them. On the second occasion, the team managed to speak to Sajjad’s mother. But she wouldn’t tell them anything about her son.

Nikam is an experienced officer who was involved in operations during the Mumbai terror attacks in 2008 and also played a key role in busting the Pune module of the terrorist outfit, Indian Mujahideen. “I decided to not go to Salamabad and alert Sajjad again, but to work in a typical Crime Branch way, which is to set up a string of local informers,” says Nikam.

Nikam and his team started from Mumbai. They spoke to Sajjad’s former prison cellmates. They discovered that Sajjad was an alcohol addict. He had also told an inmate that he would never go to Pakistan (an option the police had suspected he might take) since he considered it a ‘foolish nation’.

The question now was how to operate in Kashmir. In 2016, the Valley was in turmoil after the Hizbul commander Burhan Wani’s killing by security forces. “We had very little idea about Kashmir. We realised midway from Jammu to Srinagar that we would be in big trouble if we got caught there and that it was totally unsafe for us. So we returned to Jammu and began to build informers in Baramulla district under which Uri falls,” says Nikam.

“We had very little idea about Kashmir. We realised that we would be in big trouble if we got caught in Srinagar. It was totally unsafe for us. So we built informers in Baramulla under which Uri falls” – Sanjay Nikam, crime branch inspector

Once information began to flow, Nikam and his men found that Sajjad has three brothers: Irfan, Taufiq and Amjad. After scouring social media for days, the team came across a Facebook page created by one of his brothers. A picture posted on the page showed the four brothers together at a construction site. It was clear that Sajjad was in Kashmir.

The next day, Nikam and three others left for Srinagar. They grew beards and dressed themselves in local attire. “We never took out our phones or spoke to each other while hanging around in tea shops in Baramulla and elsewhere,” says Nikam. In between, Nikam managed to slip into Salamabad, but was discouraged by what he saw there. “My informer told me that in Salamabad about two dozen households are Sajjad’s extended family; they would have lynched us had we even tried to lay our hands on him,” says Nikam.

Then they returned to Mumbai.

In early October this year, one of the informers revealed that there was heavy construction work going on for a project in Sonamarg in Central Kashmir and that many young men from Salamabad had come there to work for a particular contractor. Without losing time, Nikam and his men took the next flight and reached Srinagar again. They had no weapons with them.

Nikam and his men first went to adjoining villages around the construction site. They identified themselves as representatives of telecom company and said they were scouting for mobile tower locations. This generated a lot of interest, with people approaching them with deals for their land. According to Nikam, he told them that he would also require labourers and asked if they could help find some. A few residents went to the construction site nearby and got hold of a few contractors working there. They were asked for quotations, and with them the police team went to the construction site. Upon asking for a list of workers, the team stumbled upon a name: Sajjid. After casually asking about this man, they were pointed towards him. He was none other than Sajjad.

For the next two days, the police party waited for a moment when Sajjad would venture off the site. But he did not. On the third day, Nikam says, he decided to take his chance. He posted two of his men with the car at a distance of 100 metres. With a constable called Sandeep Talekar, Nikam walked up to the place where Sajjad Mughal was working.

It is only after Nikam spoke to him in the car, offering him an apple, that Sajjad realised who he was.

A senior police officer in Kashmir, however, disputes the final part of this story. Fayaz Ahmad Lone, Senior Superintendent of Police, Ganderbal (under whose charge Sonamarg falls), tells Open that it was his men who finally went to the construction site and arrested Sajjad. “The Mumbai team had done their work undoubtedly, but in the end I had to send my men who caught Sajjad and then handed him over to Nikam’s team at the Gund police station,” he says.

Nikam is back at work in Mumbai now. Sources in the city’s police force often complain that men like Nikam never get the recognition they deserve for the diligent work they do. “Imagine a man going to Kashmir and tracing one man after very hard work of more than a year. And yet, no reward for him,” says a senior officer of the Mumbai Police. After 26/11, Nikam was promised a reward of Rs 5 lakh by Maharashtra’s former home minister, RR Patil, but it was never fulfilled.

Nikam laughs when asked for his response. “I do my job. I get up early in the morning, before sunrise, and sit and think. It is then that I believe that the powers in the universe show me the way.”

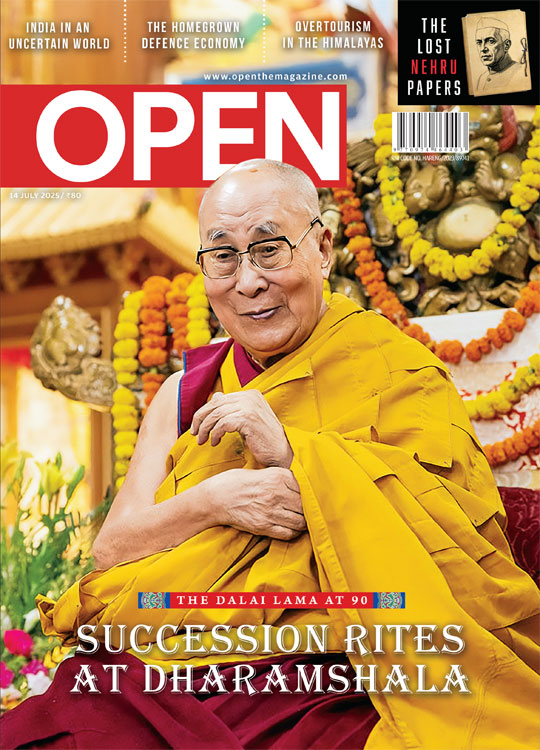

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

From Entertainment to Baiting Scammers, The Journey of Two YouTubers Madhavankutty Pillai

Siddaramaiah Suggests Vaccine Link in Hassan Deaths, Scientists Push Back Open

‘We build from scratch according to our clients’ requirements and that is the true sense of Make-in-India which we are trying to follow’ Moinak Mitra