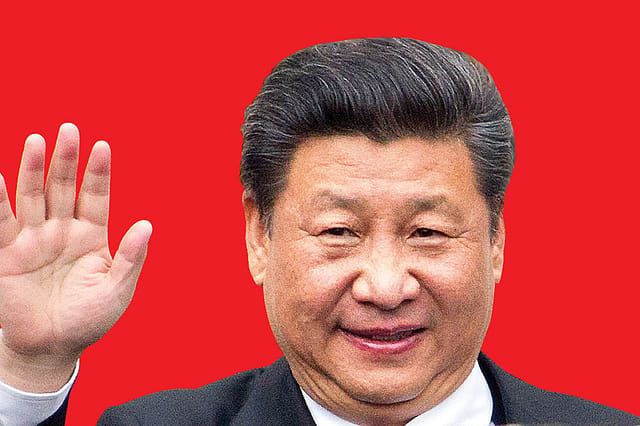

Deconstructing the Salt-and-Pepper Look of Xi

THE ELECTION ANNOUNCEMENT has rescued Narendra Modi from a quandary. He need no longer cast envious looks at the throng of admirers who copy the studiedly casual clothes and greying hair that China's Xi Jinping—Doordarshan's famous 'Eleven Jinping'—has made as much his emblem as Jawaharlal Nehru's red rose or Jomo Kenyatta's fly whisk. The severe punishment meted out to an Uttar Pradesh doctor who dared to wash a sweeper's feet confirms the Prime Minister won't allow any copycat to steal his thunder.

Yet, the contrast must secretly rankle. When Xi started going grey, at least seven of the most loyal of the 25 members of the Politburo promptly did so too. So did faithful luminaries like Zhou Xiaochuan, former governor of the People's Bank of China, Wang Yi, the foreign minister, and Liu He, a vice-premier. No, they were not like Byron's The Prisoner of Chillon whose hair was 'gray but not with years / Nor grew it white / In a single night / As men's have grown from sudden fears'. That dire fate was reserved for Zhou Yongkang, a former chief of domestic security, whose jet-black hair turned into a shock of white while he was in detention for anti-party crimes. Black hair being the vogue then, it was whispered that the hapless Zhou's punishment included denial of the dye he had always used. The 'Magnificent Seven' went grey for exactly the same reason that Congressmen in Rajiv Gandhi's time boasted of being computer addicts. Unlike the Indian Intelligence agent whom the Sikkimese nicknamed 'Go-kar' Whitehead, not because of any pimple or pustule but because of his white thatch, they knew that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. It's the Asian way.

The Indian equivalents of Zhou, Wang and Liu must, therefore, be a sad disappointment for the Prime Minister. Proudly sitting on reserves of Rs 9,68,710 crore, no governor of the Reserve Bank of India has paid Modi the compliment of cultivating his shaggy look. Sushma Swaraj must be excused for failing this particular test of loyalty; less legitimately, she is willy-nilly excused from taking the policy decisions that should be the external affairs minister's responsibility. But it must be said to her credit that she does try to demonstrate her allegiance by every so often sporting a waistcoat like the boss. Knowing her place, she is careful to ensure the garment isn't monogrammed all over. Nor, so far as anyone knows, has it ever been put to auction. The commonsensical Swaraj is aware it is most unlikely to attract bids, leave alone astronomical ones. Lacking her gender excuse, Raghuram Rajan's smooth grooming was positively insolent and should at once have aroused suspicion. No wonder two pesky governors had to be sent packing in a little over two years.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

As for the imitative Liu, India doesn't go in for vice-premiers. We did have deputy prime ministers but nearly 70 years after death, the very first incumbent has unwittingly become the posthumous prop, crutch and stick for attacking the first Prime Minister. Later deputy prime ministers like Morarji Desai or Charan Singh, to say nothing of the last incumbent, LK Advani, further justify Modi's canny decision not to risk a Number Two. In any case, it would be difficult to position a deputy in what Arun Shourie calls "a government and party of one-and-three-quarter people". If it's a "one-man show" as Shatrughan Sinha says, the Prime Minister must be his own deputy.

It's not Xi alone who shows up Modi to disadvantage. Comparison with Indira Gandhi isn't too flattering either. But no matter how flamboyant the Prime Minister's waistcoats, he remains grizzled and gravelly compared to the stylish quick change artist that was Indira Gandhi.

The morning the Shah Commission opened, it found in her a rumbustious protester in Patiala House, crumpled cotton saree hitched above her ankles, one end tucked firmly into her waist like a fisherwoman girded for battle, tousled hair like salt- and-pepper jute and not a trace of make-up. She wasn't at all the woman I had glimpsed the evening before in the Willingdon Crescent bungalow that was her political Siberia. Then, Gandhi presented a rich gleam of swishing silk under an embroidery- encrusted Kashmiri cape, exquisite make-up and, above all, a jet-black sheen of hair that fitted closely like a cap from which sprouted a single flame of dazzling white. India's former and future Prime Minister was setting out for Rashtrapati Bhavan to charm Britain's visiting prime minister, Jim Callaghan. Although dressed to kill, "there was that steel in her that would match any Kremlin leader", wrote Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew. Watching her in Patiala House it occurred to me that she had spent considerable time and effort dressing down.

Apples and oranges are not for comparison. Like must be juxtaposed with like. Modi probably regards only Xi as his peer, although someone who holds the three jobs of general secretary of the Communist Party of China, president of the People's Republic of China, and chairman of the Central Military Commission, and is hailed as 'paramount leader' by 18.41 per cent (at the time of writing) of the world's population, may not think a mere prime minister his equal. Xi is a princeling, one of that exalted Chinese version of Delhi's pampered brat pack, sons and daughters of influential party veterans. Like Mao Zedong, he sees himself as heir to the Emperor Qianlong whose letter to King George III in 1793 asserting that his 'dynasty's majestic virtue has penetrated unto every country under Heaven, and Kings of all nations have offered their costly tribute by land and sea' is still held up as history's ultimate expression of condescending arrogance. Such an august personage must look down on a politician who begs starving villagers for their votes, physically fights off those who try to foist a Muslim skull cap on his head, and suffers the jibes of aspiring females like Mamata Banerjee and Mayawati. These problems of democracy can't really be wished away by PV Narasimha Rao's prescription of solving the problems of democracy with more democracy.

Everybody in China wants to dress and look like the paramount leader not in a defiant I-am-as-good-as-you spirit but to demonstrate loyalty. No Indian does. Every Indian is his own paramount leader. The Manchus may not have been overthrown in 1912 if the Son of Heaven hadn't made it impossible for ordinary mortals to emulate his elaborate and expensive lifestyle. The 'Zhongshan suits', as the four-pocketed tunics introduced by the sturdily democratic Sun Yat Sen were called, were far easier to copy. Mao's order after the 1949 revolution that men and women alike should follow the leader's sartorial style turned everyone into a flattering loyalist. Jiang Zemin, who laid the foundations of economic liberalisation, startled the world by departing from that mould and appearing at a party congress in a lounge suit. It signified the end of ideology, warned Western leaders that Communists weren't so different when it came to money, and advertised Chinese stitching in an attempt to undercut all those suit-while- u-wait Sindhi tailors in Hong Kong. Always an astute strategist, the ageing Jiang put many princelings into key positions. As a result, their gratified fathers, uncles and even grandfathers, senior Chinese Communist Party leaders, backed him. Jiang's oversized, black-rimmed glasses which were all the rage in the 1990s were ousted from fashion by Hu Jintao's gold-framed lenses, but his lounge suits remained.

However, Xi still takes his Mao jacket out of mothballs on special occasions like formal military events because it sends two important political messages. First, it reassures a billion-and-a-half Chinese that the country will forever honour the People's Liberation Army's role in the revolution that established the People's Republic of China. Second, the civilian apparel is a reminder that the military might spread its tentacles in a string of pearls from the Cocos Island to Hambantota to the Maldives to Gwadar, but it remains subject to the CCP's political will and discipline.

Otherwise, Xi is far more innovative than Modi. The new look he is promoting—crisp, white, button-up shirts open at the neck worn with a smart blazer or a short jacket, and discarding glasses—is said to be aimed at cutting down the elitism of fellow princelings. A real man of the people would have accumulated an extravagant wardrobe like Modi. But a princeling must be seen to be a man of the masses. Hence several carefully casual tieless appearances after climbing the greasy pole. Expensive and immediately spotted gewgaws like Rolex watches and Ferrari cars are out. So are the trendy ties and well-cut suits that the former CCP secretary, Bo Xilai, sported before he was kicked out of the party. Xi is often pictured wearing a navy blue, zippered windcheater as he leads campaigns against corruption.

Now that he is going grey, his courtiers will no doubt claim it's the result of having to cope with Donald Trump's trade war, a slowing economy, and the aggressiveness of small countries around the South China Sea. But deep in their hearts, the Chinese are delighted because grey hair for them is the traditional sign of wisdom. They were not at all surprised, therefore, when Trump declared, "I have no white hair". Even Mao and Deng Xiaoping, the original paramount leader, embraced a silver-haired look in their later years. Like much else in China, tradition, like Confucianism, has often been at odds with fashion. Gleaming black heads of hair were in vogue during the Communist heyday because they supposedly indicated youth and vigour. It was like the rouge that England's ailing King George VI slapped on to keep up his subjects' spirits, especially during the challenging years of World War II. In a strategic return to tradition, 'Uncle Xi'—as he likes to be called—is using less colouring.

Modi may be three years older, but since the average age of a Chinese in 2020 is expected to be a hoary 37, compared to a sprightly 29 for an Indian, China's leader must look avuncular. Now that he is supremo for life, he might even feel obliged as the years roll on to bleach those of his tresses that haven't fallen off. From the powerful Politburo Standing Committee to provincial and local officials, everyone is keeping careful watch. The Chinese being inveterate gamblers, books may have been opened at home and among the Huáqiáo, as an estimated 50 million overseas Chinese are called, to lay bets on the greying of Xi. Meanwhile, dye sales have plummeted.

If only the May elections could be held in this demonstrably more deferential setting. There would be no reason then for Modi to ignore questions about promises to enrich every citizen by Rs 15 lakh, create two crore jobs a year or double farmers' incomes. The questions wouldn't be asked.