The Healing Project

ON January 6th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi assured German Chancellor Angela Merkel that India would deploy its capacities to combat the Covid-19 pandemic across the world. Merkel was briefed by Modi, via video conferencing, on the vaccine developments in India on the 70th anniversary of the Indo-German diplomatic relationship and the 20th anniversary of the bilateral strategic partnership. The German federal government's spokesperson, Steffen Seibert, tweeted later that the two leaders discussed the pandemic, advances in vaccine development and production in the Indo-Pacific region. But this wasn't the first time Modi and Merkel were talking about vaccine developments. Merkel was the first to call and congratulate Modi on his Covid containment strategy in a nation the size of India soon after the prime minister announced the emergency use authorisation (EUA) granted to two vaccines, both made in India. The lauding of Modi's efforts came days prior to Bharat Biotech signing an agreement with Brazil on vaccine supply.

Merkel's was no hollow appreciation. An editorial in the New York Times a fortnight ago had detailed how, in the US, the number of people vaccinated was nowhere near the two crore target set by the end of 2020. Of the 1.4 crore vaccine doses delivered to hospitals and health departments across the US, a mere 30 lakh estimated people had been vaccinated. In one Kentucky county, pharmacists had even retrieved vaccine shots dumped in garbage bins and offered them to lucky recipients on the spot. In India, the chain from the vaccine manufacturers to individual recipients is a long and complex one and would need stringent monitoring to iron out glitches notwithstanding the country's history of vaccine success with polio and other ailments.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Five days ahead of the January 16th rollout across India—the largest in the world to date—Modi spelt out his Government's detailed plan to the chief ministers: the exercise would cover three crore first response workers in the first phase, including one crore medical professionals/health workers and two crore other Covid warriors, including sanitation workers, ambulance staff, those working in burial grounds, crematoria and civil defence personnel, totally free of cost. The second phase would be for those above 50 years of age and those younger but with co-morbidities, roughly around 27 crore in all. The Government had capped the price per shot of vaccine at Rs 200. Asserting that he was proud of the two India-made vaccines, AstraZeneca-Serum Institute of India's Covishield and Bharat Biotech's Covaxin, the prime minister pointed out that India now had the privilege to be the pharmacist to the world in combating the pandemic. The presidents of Brazil and Ecuador, Jair Bolsonaro and Lenín Boltaire Moreno Garcés respectively, have already requested India for urgent supplies of the vaccine and several nations are in queue for vaccines from the world's largest vaccine-maker.

Holding out assurances about both vaccine efficiency and efficacy, Modi said that the world was also observing the nation's long established vaccine literacy lessons and experience and how these would impact the successful execution on the ground of the current exercise. Modi also told the chief ministers that by the time the second phase started, four more vaccines would be available to the public, making it that much easier to plan and execute the rollout for the much bigger second phase.

The rollout plan for a population of 1.3 billion was not a cavalier exercise. Nor was it blueprinted overnight. It was initiated months ago by Modi following prolonged meetings with pharma industry leaders. As far back as April 2019, he had urged the industry to consider the nation's battle against the pandemic as their "bounden duty" and focus pointedly on vaccine development. Some of those present promptly asked for huge state funding. Without demur, Modi tapped the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to allot funds for research. That was barely weeks after the Wuhan-origin virus had led to untold misery, a devastated economy and forced reverse migration. Modi was battling an unknown enemy. The World Health Organization (WHO) had not shared the sequence of events, next to nothing was known about the rapidly spreading virus and Modi, trying to impress upon people how dangerous the developments were by enlisting their support through hand-clapping and thaali banging, was under attack from his detractors about the stringent lockdown.

But Modi's detractors in the political arena seem to be following their now familiar path—using even the vaccine success for cranking up the anti-Government rhetoric. Jairam Ramesh said it was puzzling that internationally accepted regulatory protocols were modified for Covaxin trials. The fact that Covaxin's first dose in the Phase 3 trial data for 22,500 volunteers was analysed by experts appears not to be the least important to the vaccine sceptics among Modi's critics.

Bharat Biotech is a traditionally sound, tried and tested company which has a legacy of coming to the aid of the country in times of health distress. As a leading manufacturer of innovative Hepatitis B vaccines, it supplied a million doses for the National Immunisation Programme at Rs 10 a dose. At a time when Big Pharma controlled by MNCs was selling it at Rs 1,400 a dose, it was Bharat Biotech that supplied affordable vaccine to the country. It was also the company that led the fight against Rotavirus that affected lakhs of Indians. A company with such sound credentials and credibility, a proven warrior, was being tarred with a nasty brush by Modi's detractors in a concerted fashion to score brownie points.

Confusion about vaccines does immense damage to immunisation programmes run by the state and creates a trust deficit in the public about the hard work put in for prolonged periods by professionals. And a trust deficit takes ages to bridge in the minds of people. None of this appears to have distracted Modi's critics from their primary goal of dissing every considered decision and politicising his intentions, irrespective of how unsuccessful their efforts ultimately prove to be. Even Gagandeep Kang and Kiran Mazumdar Shaw were roped in. The director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Randeep Guleria, had said that Covaxin could be kept as back-up for the rollout until after the Phase 3 trials were completed. This was twisted to amplify questions on the credibility of the Hyderabad-based vaccine producer. The line of attack was as familiar as the rhetoric: under Modi, India has entered a coercive era of medical tyranny and vaccine nationalism.

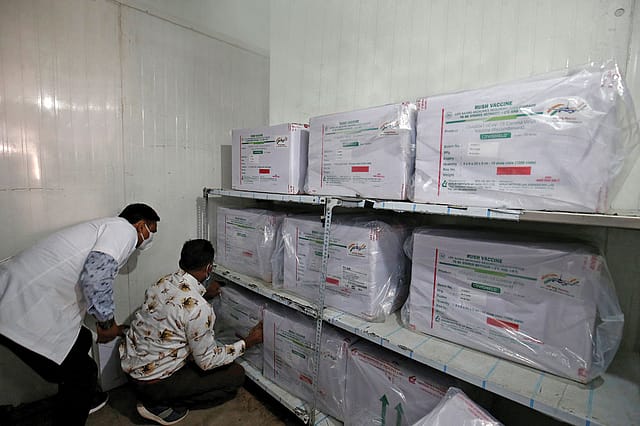

On January 12th, at the end of a long and anxious period of countrywide anticipation, the first doses of the Covishield vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India (SII) were finally shipped to six cities from Pune. In all, the Government shipped out 56 lakh vaccine vials earmarked for 13 cities. There were emotional scenes—tears of relief, joy and pride, selfies and spontaneous clapping—as the first batch of vaccine consignments were unloaded at the Rajiv Gandhi Hospital in Delhi and in Chennai, where five lakh vaccines, both Covishield and Covaxin, were flown to. Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Kolkata were other cities which received vaccines, and Mumbai was to follow soon after.

Such emotional scenes as the consignments arrived at various destinations were understandable. The vaccines are not just protection from a pandemic that has taken over 1.5 lakh lives in India. They are a telling metaphor for the revival of the economy and the return of normalcy in a nation under lockdown for most of a year. Workplaces, schools, small industries, trade, business, even the most basic economic and social activities, had been affected in this period, devastating the most vibrant of societies worldwide. The rollout in India—the second most populous country—will serve that macro effort of dispelling the insecurities of a wretched year that decimated life as we had known it, life as it was lived and experienced before 2020.

However, as the country stands on the verge of a momentous executive and scientific feat—making not one but two vaccines—it has sparked a different type of concern among the regime's opponents. The developments on the vaccine front spell doom for those hoping to stage a comeback on the political front—something they have not been able to do successfully at the hustings—by tripping Modi.

Their hopes of Modi's failure on Covid management and on vaccine manufacture and rollout were reinforced and selectively amplified by tapping into a small network of fearmongers among the scientific community. Every setback in containing the spread of the pandemic was magnified in the initial days, exponentially raising fears of infection and fatalities among the public.

Despite that, India defied the scenarios of doom peddled by anti-Modi activists disguised as Covid clairvoyants. They had also predicted mass starvation and destitution as a result of unemployment. True, the economy contracted, jobs were lost, and people's incomes crashed, cutting across class. But the predictions of mass starvation and destitution came to naught, given the Government's timely and tailored new schemes and the revamping of the older ones to ensure cash in the hands of the rural unemployed and migrant workers forced to return to their villages after their workplaces shut down. In addition, supply of additional free foodgrain to the eligible, right up to Diwali and beyond, ensured there were no starvation deaths. The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana and Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana were boosted and became key conduits of direct relief to the most affected.

Modi's opponents have continued to find fault unrelentingly with his Government's handling of Covid. But it has become clear that people at large are more than satisfied with the manner in which he handled the situation and nowhere has this been proved decisively than through the ballot. In the past year, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has chalked up electoral successes time and again, from civic polls to panchayat elections to state Assembly elections and bypolls; from Jammu and Kashmir to Bihar, Telangana to Madhya Pradesh (MP). In fact, 2020, despite the all-pervasive distress, could well be known as BJP's year. In Bihar, the party became the second largest, with 74 of 243 seats, only one seat less than the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) which emerged as the single largest outfit. BJP returned to power in Patna with the Janata Dal (United) towards the end of the year, but as the clear heavyweight in the alliance. It also wrested the Dubbaka Assembly by-election from the ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) and put up an impressive show in the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation polls. The same was the case in the MP bypolls and in Rajasthan, even as the Congress performed abysmally. Modi retained more than his personal credibility and popularity.

Irrespective of the politically motivated narratives crafted by the opposition, the fact remains that the prime minister's intervention and owning of responsibility in urging pharma industry leaders early on in the pandemic went a long way in conveying the urgency of vaccine development in India. India has been able to take a huge leap taken by Big Pharma elsewhere without state oversight of any sort.

Self-styled experts here objected to virtually everything that prevailed in other developed countries, including shorter deadlines, abridged trials, insufficient peer review and lack of transparency on trial data, to cry wolf about the efficacy of the vaccines.

Without compromising safety or efficiency, the likes of Pfizer and Moderna availed of concessions from the UK regulator to deal with the emergency situation. No questions were raised by the vaccine sceptics here about these shortcuts, but Modi baiters criticised the same in the case of India's own commendable efforts.

Only the very naive can claim that vaccine and science can be totally insulated from politics. In the wake of Covid and the race to find a cure, 'vaccine nationalism' has become a familiar phrase in the realm of politics. Additionally, in a democracy, everything about vaccine development, clearance and rollout, platforms and costs, is certain to become part of the debate. That is as it should be. For, public health is too sensitive an issue to be left solely to pharma 'experts'.

But while one can debate, hold a government to scrutiny, the line cannot be crossed into overt politicising of public health, especially in a pandemic. It is ironic that the very same people questioning the delay in the manufacture of vaccines have now shifted the goalpost to question the efficacy of the vaccines, particularly Covaxin.

Cynicism is now giving way to outright opportunism. The fear-mongering is aimed at causing vaccine scepticism among a section of the population that has always seen such efforts as conspiracies against their faith and meant to cause serious bodily harm, such as infertility and so on. Statements from Samajwadi Party's Akhilesh Yadav and RJD's and Tejashwi Yadav—the former called it "BJP vaccine" and the latter asserted that he would get vaccinated if Modi would lead by example and take the vaccine first—seem to be meant to increase vaccine aversion among already vulnerable sections.

Casting doubt on established regulatory processes followed by vaccine companies with a credible background was not enough. In tandem with the political opposition to Modi, activists and NGOs have also jumped in at this critical vaccine rollout time to claim that in some pockets in Bhopal, in BJP-ruled MP, the poor and Bhopal Gas Tragedy victims' families have been targeted with a payment of Rs 750 to enlist in Covaxin trials, many with no phone connections and not even aware that they were part of a trial and not the larger official government-driven vaccine rollout to begin only on January 16th. It is important to note that in countries like the US, there have been loud protests about Moderna: not enough African-Americans and Latinos were being included in the vaccine's Phase 1 trials. The concerns prompted the company to proactively enlist more from among these groups in the second phase. Critics here are, no doubt, just as acutely aware that if samples of vaccine-testing in Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials are not representative of all groups, the conclusions are unlikely to be considered fully credible.

The Government, however, had anticipated this line of attack—especially on alleged opaque efficacy data on vaccines slated for rollout and on the equity aspect. It was to counter this deliberate disturbia that the prime minister announced that three crore people in the first phase of rollout would be vaccinated free of cost. Apart from other issues, this also called out those claiming their state governments would provide free vaccines to all state residents, a move seen as purely politically motivated. In other opposition-run states, such as Chhattisgarh, the governments have fallen prey to their own rhetoric and demanded supply of only Covishield and not Covaxin. With that one decisive move, Modi has managed to put to rest the falsehoods peddled about the vaccine rollout. While countries like the UK and Sweden, and even Israel, have been forced to repeatedly restart lockdown following a resurgence of infections, after first having eased up on this, Modi has remained on top of the criticism from his detractors and steps ahead of his political opponents.