The Future of Entertainment

The pandemic has changed the art and mart of movies. Forever?

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

|

28 May, 2021

|

28 May, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CinemaCover1.jpg)

(Clockwise from top Left: Akshay Kumar in Sooryavanshi; Salman Khan in Tiger 3; Aamir Khan in Laal Singh Chaddha; Ranveer Singh in Cirkus and Ranveer Singh in 83)

Bollywood’s edifice has come crashing down in the pandemic. A limited distribution system, movies far removed from life and streaming giants have amplified its biggest crisis: the nationwide closure of movie halls. No one is sure whether it will be happily ever after once theatres reopen

CHAIRMAN OF PVR PICTURES, AJAY BIJLI, ONE OF the most powerful men in the film industry, is happy watching re-runs of the cult 1994 movie, Andaz Apna Apna, to keep his mother company. His longtime friend, actor Aamir Khan, is working out ways to organise a biobubble for his long-delayed shoot in Ladakh for Laal Singh Chaddha. Deepika Padukone, having just recovered from Covid-19, is waiting to wrap up her newage infidelity story with Shakun Batra before she starts on Nag Ashwin’s next with Prabhas. And Hrithik Roshan, who was all set on May 8th to begin Vikram Vedha, with Saif Ali Khan playing his antagonist in the Tamil remake, is listening to script narrations. For an industry looking down the barrel of a gun, the calm is remarkable. Bijli, who controls almost 900 of the 9,527 (as of 2019) screens in the country, has mentally written off two years of growth. Until there is enough vaccination, he knows audiences will not return to theatres. That’s not likely until at least the end of the year, so he sees no reason to fight the inevitable. “Even when I speak to my friends in the industry, business is the least of our priorities. We’re just grateful to be alive.”

Theatres may be shut, but Bollywood is hard at work. It expects, when the country emerges from the pandemic, people will want to watch films on the big screen. They point to the opening weekend numbers of Fast & Furious 9 at the global box office—$162 million—with the movie not even having opened in the US. They also underline how the decision by WarnerMedia’s HBO Max to release their 2021 films on the streamer the same day they hit theatres cost it more than $1 billion and hastened its stake sale by parent company AT&T to Discovery. In India, there is demand. It’s just been temporarily diverted to OTT platforms, with a total of 58 million subscribers and 400 million unique viewers, and television, which has 780 million viewers. There is hope, in the long run, but there is also anxiety. Bollywood’s future is a contradiction.

Some of its problems are structural. Stymied by a distribution system comprising shiny new multiplexes usually built as part of malls or on the shells of rundown theatres with evocative names, it is enormously underserved by screens. Its per capita screens is among the lowest in the world, 9,527 screens for 1.39 billion, compared to the US which has 40,998 (2020) screens for 330 million people, and China, which has 75,581 screens for its 1.4 billion people. Bollywood’s stories, borrowed from earlier films rather than life, are increasingly sounding false to vast swathes of the country. Its global market is a mere 20-25 per cent of the overall box office revenue. With millions of phone screens—India has 500 million smartphone users likely to rise to 700 million in the next three to five years—downloading and watching inexpensive, subscriber-driven entertainment, thanks to the Jio mobile network, the Hindi theatrical business was already under-monetised when Covid struck.

Bollywood’s inhabitants should have seen the disaster coming.

SOFT POWER, BUT NO HARD NUMBERS

But for that one needs to build a sustainable exhibitors’ chain in good times and develop domestic digital giants with transparent payments systems instead of relying on foreign “cash cows” with supposedly deep pockets. And it needs to tell stories the world wants to watch. In the cultural war of the theatre vs the shrinking screen, India with its entertainment-hungry millions could have become a global leader. Instead, with its tradition of fuzzy numbers, it is struggling to count the revenue from the pay-per-view release on May 13th of Salman Khan’s Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai. Bought by Zee Entertainment for a reported Rs 200 crore, Radhe’s opening day numbers of 4.2 million views—the first time a platform has given numbers—were good but not immediately comparable to potential box office revenue because it is not clear how many were views enabled by fresh payments or existing subscribers. For Zee, it will no doubt turn in a profit over a lifetime; in the case of Salman, the producer, it is already more than what he spent. Will the movies that are piling up adopt a pay-per-view-(or TVOD, Transactional Video on Demand)-cum-theatrical model as Radhe: Your Most Wanted Bhai did? Will they go straight to subscription-led streaming platforms (SVOD, Subscriber Video on Demand)? Or will the studios prefer to wait out the storm, batten down the hatches and then release the flood when India is mostly vaccinated?

It is a crisis of the kind that Bollywood has not faced before. At least not since it was given the designation of an industry by then Information and Broadcasting Minister Sushma Swaraj and the influence of underworld money receded. Yes, it has had controversies since, most famously in 2008, when two classmates from Bombay Scottish, Aditya Chopra and Shravan Shroff, squared off against each other, producers vs exhibitors, on the revenue share for Tashan. It took a phone call from Yash Chopra to Shroff’s uncle, Cinemax founder Rasesh Kanakia, to end that impasse. Last year, it was confronted with a storm over its worst practices, from rampant nepotism to drug abuse, sparked by the death by suicide of rising star Sushant Singh Rajput.

Now, even as the country grapples with the second, deadly wave of Covid-19, the industry is facing its toughest test yet. As it braces for a long, dry spell at the box office, it can use its time to do more of the same or to do more of the extraordinary. The latter requires courage and flexibility. Courage to recognise that it is no longer the only game in town; it has to compete with Hollywood and regional cinema—the only movie to cross Rs 1,000 crore at the domestic box office was Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017), in Telugu and Hindi. And flexibility to understand that the stories it is telling are not connecting with a wide enough world.

The problem is not merely of the kind of stories Bollywood tells but also how big the audience for these is. Distribution has been Bollywood’s greatest bugbear, limiting its industry to a revenue of $1.6 billion, which is less than what one Hollywood blockbuster earns—$2.7 billion is what Avengers: Endgame earned at the global box office in 2019. One reason is Hollywood is no longer dependent on its domestic market. Over 60 per cent of its cumulative box office revenue, $11.4 billion (2019), comes from outside America. China doesn’t even need the rest of the world. Its domestic box office alone is $9.3 billion (2019), of which 85 per cent (2020) is from made-in-China movies, up from 60 per cent in 2018. Hindi cinema is limited at home and globally.

Bollywood’s soft power is enormously underleveraged, partly because of piracy and partly because of the geographical spread of the diaspora. Film scholar Daya Thussu, who in 2013 wrote one of the early expositions of Indian soft power, titled Communicating India’s Soft Power: Buddha to Bollywood and who, as someone who has lived and worked in London for three decades and is now based within the Sino-sphere, can say with confidence that Bollywood remains one of the most visible instruments of India’s cultural and creative power. Increasingly, he says, “It circulates on various digital devices and platforms and its import cannot be observed simply by theatrical releases, especially globally.”

The Indian film industry’s relationship to globalisation has always been paradoxical, points out New York University professor Arvind Rajagopal. On the one hand, it is highly knowledgeable about foreign trends (for instance, the way Western beat and rhythm was brought into film music here). At the same time, it has been quite insular culturally. “To give just one example, for many years, the only time we saw white people in HIndi movies, if at all, was when international smugglers met to divide the heist of diamonds, and since those white people were probably recruited without much selection available, we only saw them in very long shots,” he says.

FABRIC OF INDIA AND BOLLYWOOD WEAVE

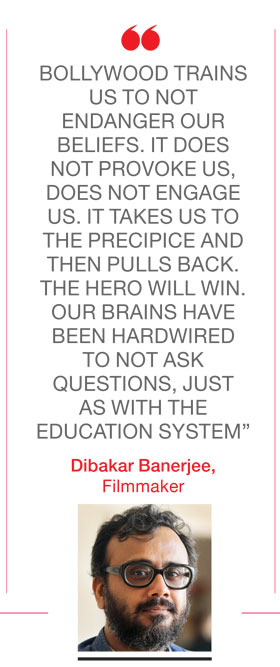

The other part of the story is the subjects Bollywood chooses. In the last 10 years, they have moved towards a kind of positive, nationalist realism. Filmmaker Dibakar Banerjee ascribes it to two things. One, every script now has to have congruence with some film we have seen before. The sheer number of films we have seen and the sheer lack of life we have lived have hardwired this into our brain. Two, he believes Bollywood is deeply programming and training audiences to accept a narrative removed from the fabric of life. “Bollywood films are not meant to provoke you, or endanger your beliefs or engage you. The hero will win, now you just have to go through enough gags till you get there,” he says.

Not surprisingly, parts of India that ought to be watching Hindi films have stopped doing so. Why? M Rajshekhar, who spent 33 months researching his book, Despite the State: Why India Lets Its People Down and How They Cope, posed this very question to youngsters in Bihar and Gujarat. And each time, it seemed that they identified more with stories (and characters) in south Indian cinema than Bollywood or their own cinema. Imagine, he says, “three youngsters, all around 21 years, who earn a living driving auto-rickshaws in Bhagalpur. I met them outside the medical college in the town. Waiting for customers, they were sprawled over the backseat of one auto, watching a south Indian movie on their phone. Think of their lives. They live in a town that is rundown. Their experience of education will be broken-down school buildings and overcrowded classrooms. Their experience of life is about them being pushed into work at too young an age”.

Talking to them—and subsequently, with a bunch of other youngsters in these two states—it just seemed that they related more with characters and narrative arcs of films from the south, be it the hyper-violent vigilante movies (Ajay Devgn’s Singham, 2011, was a remake of such a film) or more straight-forward aspirational tales. One instance he was given: a film with Junior NTR where a son wants to meet his father’s expectations. Bollywood doesn’t match up. It’s too unfamiliar. “Too many of its sets are too glitzy to be relatable for these young people in the hinterland. Too many of its story plots are too esoteric for them. Even the films made about the hinterland—Peepli Live (2010), Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), Article 15 (2019), everything by Anurag Kashyap—are essentially urban looks at rural areas,” he points out.

Will a new hybrid model of distribution—digital plus theatrical with no window or a very limited window—expand the market? Applause Entertainment CEO Sameer Nair points to how much the mode of entertainment distribution has changed in our lifetime. From the early single-channel days of Doordarshan to the boom years of satellite television to global streamers, how we can and will consume content has changed. “This in turn has changed us as consumers, changed our behaviour and hence our tastes. Social media has also played a huge role in this transformation. While the current pandemic has accelerated digital adoption, it has also fatally wounded theatrical distribution,” he says.

SMARTPHONES DON’T DECIDE STARDOM

Theatres have to respond by refining and differentiating their experience, as and when the pandemic permits. Inexpensive data since the public launch of Jio in 2016 has meant the rise of the phone screen. But smartphones don’t decide stardom. Theatrical revenues still remain the true measure of ‘elastic revenues’ and ‘superstardom’. Removal of theatres from the distribution equation may only make the remaining gatekeepers, streaming giants, even more monopolistic, and in the long run, will reduce rather than increase the monetisation potential of the film industry. Currently, Netflix has 4.6 million subscribers but because of the pricing, it controls 45 per cent of the subscription video business; Amazon Prime Video has 17 million subscribers and Disney+Hotstar has 26 million subscribers. More players are expected to join, with Apple TV+, NBCUniversal’s Peacock and WarnerMedia’s HBO Max poised to expand in India over the next few months.

There is much celebration in Bollywood over the Fast & Furious 9 numbers, but the industry will need similar superhero megablockbuster firepower to keep cinema alive when all else is losing. Unless it does so, Bollywood will lose to OTT platforms. As Kaushik Bhaumik, associate professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, says: “Why watch even a Gangs of Wasseypur in theatres when you can watch Mirzapur on your mobile phone? So I wonder what Bollywood will do post-pandemic. Make small films for niche audiences? Maybe. But that’s not an industry.”

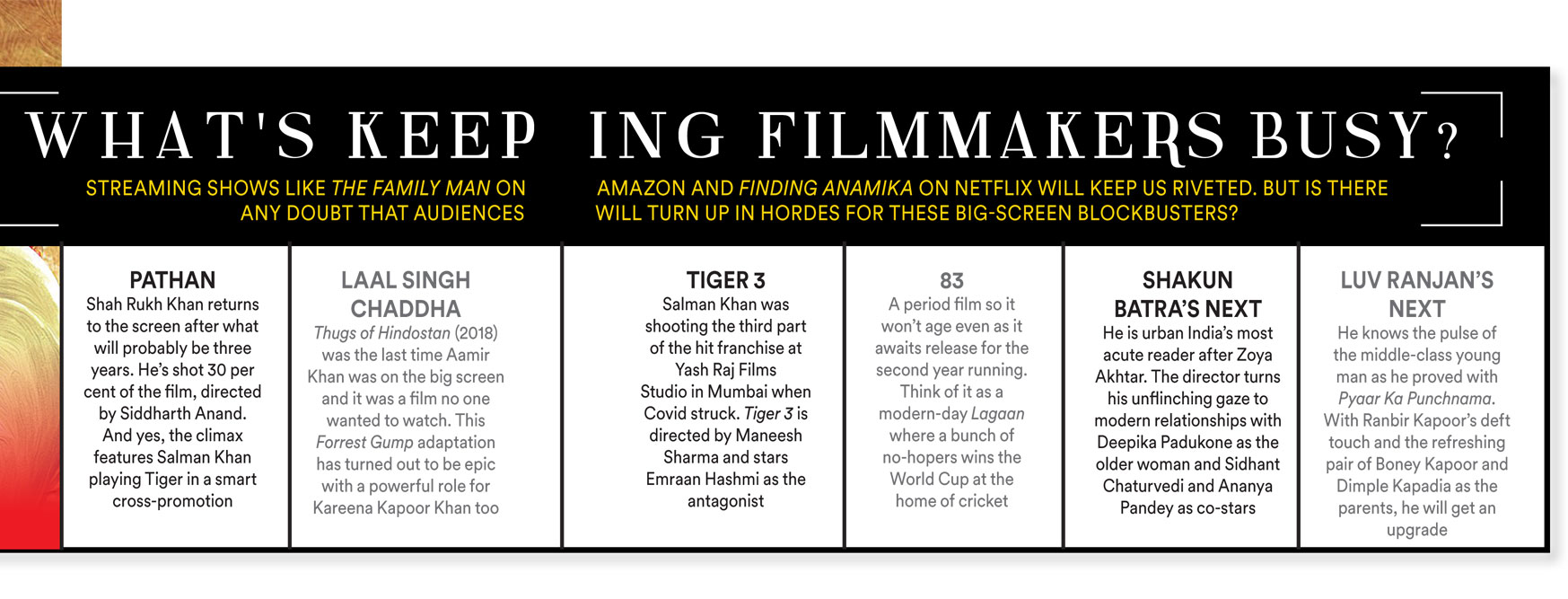

Yash Raj Films is working on big action films to fill this superhero gap: after War in 2018, it is currently shooting Tiger 3 and Pathan, with a cross-promotion between them in the climax of Pathan. But there are only a handful of stars currently capable of bringing in audiences. Reliance Entertainment has had two such wannabe blockbusters ready since last year: Sooryavanshi, Rohit Shetty’s copper franchise starring Akshay Kumar as well as Ajay Devgn and Ranveer Singh, the stars of his Singham and Simmba (2018) respectively; as well as 83, about another kind of superhero, Kapil Dev. Shibasish Sarkar of Reliance Entertainment points to the Chinese box office which has, like the US box office, returned with a vengeance. He points to the top 10 movies at the Chinese box office between March 2020 and 2021: all are made in China and have crossed $100 million, with the top film, Hi Mom, making $823 million since its February 12th debut.

The bottomline is that Bollywood is broken, and Covid has merely accelerated the self-destruction. The industry does not make enough legitimate money to justify its exalted status in society, it has only a few stars who are highly paid and instead of corporatising, as it did briefly when six foreign studios tried their luck between 2007 and 2015, it is a curious mix of the old and new: a handful of family-run studios such as Yash Raj Films, ALTBalaji; production houses like Excel, Applause, Tiger Baby Films and Nikkhil Advani’s Emmay Entertainment; financiers such as T-Series; and independent filmmakers like Hansal Mehta, Anubhav Sinha and Anurag Kashyap.

It’s a far cry from the earlier disparate group of 20-odd producers and 20-odd distributors, but no less personal in its choices. The platforms, apart from theatres, are foreign giants such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Disney+Hotstar. Could they, at some point, displace the existing distribution systems much like Facebook, Google and YouTube put a squeeze on print and television? For now, though, they are being perceived as saviours, with Netflix especially acting on its global mandate of diversity behind and in front of the scene, and its CEO Reed Hastings announcing in 2018 that the next 100 million subscribers would come out of India. With a few exceptions, though, the big OTT players in India are imposing a very top-down idea of programming for their urban, upmarket audiences, feels film scholar Vamsee Juluri.

The gap between the creative class’s vision of India and the audience is not only a class one but increasingly a transnational one. This trend started with MTV in the 1990s itself where American employees of Indian origin were parachuted to invent the local programming vision. Juluri, professor at the University of San Francisco, says it reminds him of Lisa Lau’s concept of “re-orientalism” with American second-generation executives and Indian Anglophone elites enacting their vision of what is good for Indian audiences commercially and maybe even morally/politically. “As a result, there haven’t really been rooted/global crossover shows on OTTs from India, I feel. Shows like Sacred Games and Ghoul (2018) got a lot of attention but I don’t see my students, for instance, really pick up on anything on Netflix or Amazon Prime from India compared to other international shows,” he says.

IS IT THE INTERVAL OR THE END?

This underlying disconnect, which one sees in students in Bihar and Gujarat, is equally evident in big cities. But it is not something all exhibitors want to address currently. Blaming Covid for their problems is easier to do. CEO of INOX Leisure Ltd, Alok Tandon, says the film industry is witnessing the most unusual times, which has made some stakeholders take decisions which have nothing to do with the inefficiency of the theatrical system. “Not just the exhibitors, but the entire value chain in the industry understands the significance of the theatrical system, as it ensures a win-win for every player on the value chain, be it the producer, the content creator, the performers, the distributors, besides the cinema exhibitors.” INOX, which controls about 650 screens, believes there will be a comeback and they will be able to continue with the standard way of doing business.

It’s called the Lindy Effect where, Nassim Nicholas Taleb says, the observed lifespan of a non-perishable item is most likely to be at its half-life. So if a business is 100 years old, it should expect to be around for another century. And a business that has been around for 10 years will last another decade. By that token, cinema, which began in 1895, will last longer than streaming, which began with YouTube in 2005. After all, the VCR was once described, quite politically incorrectly, as the AIDS of the movie industry by iconic movie director Manmohan Desai. All it took was 14 songs, a wedding, a funeral and Madhuri Dixit in Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994). Producers Rajshri released a mere 26 prints and then insisted only theatres that upgraded their facilities would screen their movie. The middle class came back and within three years, PVR built the country’s first multiplex.

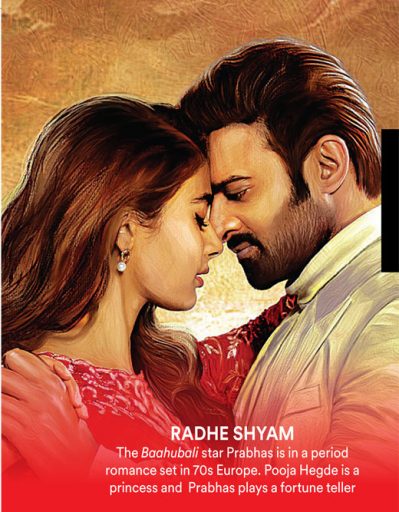

But in the interim, what of stars, those magical creatures who capture our imaginations on the big screen and visit us in our dreams? Will the Khans, Ajay Devgn and Akshay Kumar, and the only star created post millennium, Hrithik Roshan, be the last of the titans? Streaming services create actors, but stardom is still a measure of the number fans that turn up at the box office—not surprisingly, southern fans who have a special status for their movie stars watch 12 movies a year while Hindi film fans make only four trips a year to theatres. Despite the doom and gloom, the industry is confident it will have enough entertainment to satiate audience hunger when theatres reopen: Salman Khan’s Tiger 3, Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathan, Aamir Khan’s Laal Singh Chaddha, Cirkus with Ranveer Singh, Prabhas’ Radhe Shyam, Ranbir Kapoor’s light romance for director Luv Ranjan, and Hrithik Roshan’s Vikram Vedha remake.

The question is: When will they reopen and will we, vaccinated, masked-up, sanitised and socially distanced, enjoy the experience?

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Jasprit Bumrah Captain? Shubman Gill His Sidekick! Short Post

Our response will be fierce and punitive, says India Open

IAF pounding of air bases, command and military infra forced Pak to seek ceasefire Open