Desire Is Destiny

The erotic road to freedom

Alka Pande

Alka Pande

Alka Pande

Alka Pande

|

09 Aug, 2024

|

09 Aug, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/DesireisDestiny1.jpg)

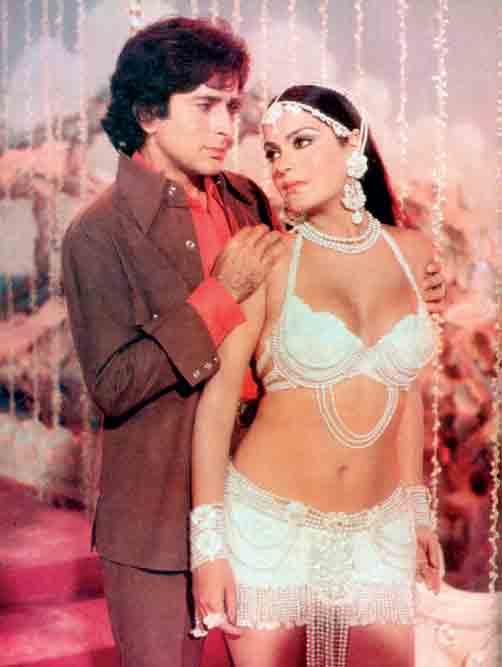

Rekha

HOW DOES ONE VIEW THE STATUS of sexual freedom for women in contemporary Indian society? Have same-sex relationships come of age? Are they now a part and parcel of an inclusive and civil society?

My study of the aesthetics of the erotic in Indian visual culture, Indian cinema and particularly traditional Indian literature sheds light on the above questions.

What I find contradictory is the representation and attitude towards women in India. At one level she is the supreme ‘shakti’ who has been worshipped since the dawn of Indian civilisation. At a religious and philosophical level, feminine power is sacred and powerful. She is the primordial mother, the all-pervading energy to which the three primordial gods, Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh bow to. Philosophical texts place the woman on a pedestal. Chamunda, Chhinnamasta, and Kali, become embodiments of fear, fierceness, and power.

Our sages, our philosophers over 5,000 years of civilisational history, have reflected on sexuality, erotica, human behaviour and inclusiveness. In the Vedic hymns desire comes as a precursor to sexual gratification.

Mahadevi in the form of Mahakali, Durga as Chamunda, she is ferocious and reeks of annihilation. As Maha Lakshmi, she is the epitome of wealth, beauty and splendour and as Maha Saraswati, she portrays knowledge and enlightenment. In her many lesser manifestations she is shown in her benign form as a nurturer, as the patron of the arts i.e. Meenakshi.

At a celestial level, the woman is represented as an apsara, a celestial nymph imbued with extraordinary beauty and as the ultimate seductress. As Rambha and Urvashi, she is known to have seduced the greatest of sages and ruined the years of sadhana thus causing a devaluation in the power of the sages. From this lineage apsaras descend into devadasis who in the medieval period become tawaif or courtesans.

When I think of sexual freedom the word Ganika flashes before my eyes and the image which confronts me is the gloriously beautiful Rekha as Vasantsena in the 1984 film Utsav. She is shown in an intimate scene with her married lover Charudatta. Vasantsena epitomises the ultimate empowered woman who is the mistress of her luxurious palace, having a bevy of beauteous handmaidens, attending to her every whim, as she commands her entourage to do her bidding.

Shringara or adornment permeates her being. From perfuming her hair to colouring her lips, darkening her eyes, beautifying the self is as important to the ganika as is the excellence in the arts of music and dance, and writing poetry.

The ganikas or courtesans were an extremely important part of Indian society, be it Amrapali, the Nagarvadhu of Vaishali or Muddupalani, the revered poet from Andhra Pradesh or the famous Anarkali, the love of Jahangir.

To me sexual freedom is embedded in the Ganika of pre-modern India, the tawaifs of medieval and modern India who morphed into prostitutes of contemporary India, the heavenly apsaras who descended from the heavens, be it Urvashi who was sent to demolish the tapasya/sadhana or meditation of the great ascetic sage, virtually a modern day honey trap, to the Matsyakanya, Satyavati, to the mother of the Pandavas, Kunti.

Cut to the present. The tawaif popularly known as baiji in North Indian parlance is the muse of the great operatic series Heeramandi on Netflix. Though high on TRP ratings Heeramandi presents a rather skewed representation of the tawaif who is on the lookout for a rich nawab who either would be her patron or in some fantastical hope marry her and make her his begum. On the other hand, I saw an exceptional and meticulously researched production by the Kathak dancer Manjari Chaturvedi, Main Tawaif. Chaturvedi presented the tawaif as a culture bearer, as a custodian of the tameez and tehzeeb of the life and times of the upper echelons of India’s syncretic culture. Where the tawaif is truly an empowered woman with great agency. Young men were sent to her to acquire the graces of nobility. In fact, Chaturvedi’s personal favourite is a tawaif from Hyderabad, Chand Bibi or Mah Laqa Bai who is the embodiment of a woman who enjoys her sexual freedom and lives life on her terms. Born in the late 1700s, she was omarah (the highest nobility) in the court of the Nizam and even accompanied him in two wars. Renowned for her singing and dancing, she also ran a training centre where hundreds of girls studied music and dance.

Rekha as Vasantsena in the 1984 film Utsav epitomises the ultimate empowered woman who is the mistress of her luxurious palace, having a bevy of beauteous handmaidens, attending to her every whim, as she commands her entourage to do her bidding

Through her painstaking research, Chaturvedi discovered that in one of her letters translated by scholar Bilkees Latif, the young woman informed her mother that she didn’t want to get married, and refused to be part of anyone’s harem. Mah Laqa expressed her desire to remain independent, managing her own affairs and caring for people. She had chosen her lovers based on her own desires and pleasures, rather than societal expectations or economic necessity, demonstrating a remarkable sense of autonomy and empowerment.

Historically, tawaifs were much more than mere courtesans; they were accomplished artists in music, dance, and poetry, serving as cultural institutions where the nobility learned various forms of etiquette and art. Contrary to their often-misrepresented portrayals in Indian cinema, their residences, known as kothas, were centres of high culture and education.

However, over time, the status of tawaifs reduced, and their art was disrespected, marginalising them and denying them the recognition they deserved. In some ways, cinematic representation has often destroyed the very essence of the culture of the tawaifs. For instance, songs originally composed and performed by tawaifs, such as Bajuband Khul Khul Jaye and Hamar Kahin Mano Rajaji were reinterpreted in films, stripping them of their original context and meaning.

The popular soap Heeramandi however emphasises a particular version of the lives of tawaifs, and misrepresents them by depicting them in a derogatory light that emphasises sexual gratification and power struggles, rather than their artistic and cultural contributions. The series, while visually stunning, conflates different categories of performers and fails to acknowledge the high level of artistry and education associated with tawaifs. This portrayal perpetuates stereotypes, reducing tawaifs to objects of sexual desire. Historically, tawaifs like Jaddan Bai Hussain and Gauhar Jaan were influential in music and filmmaking, but Heeramandi reinforces stigma and misconceptions, failing to honour their true legacy.

IN THE 1950S AND 1960S, INDIAN CINEMA BEGAN subtly addressing themes of love and passion. Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1951) used song and dance to suggest romantic and sexual desires in a conservative social context. Guide (1965), based on RK Narayan’s novel, explored themes of extramarital affairs and female sexual autonomy, presenting a bold narrative for its time. The 1970s and 1980s saw films that began breaking taboos more openly. Raj Kapoor’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978) faced criticism for its bold portrayal of female sexuality, and Zeenat Aman’s character’s physicality. Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth (1982) delved into themes of extramarital affairs and a woman’s journey towards self-discovery and independence, challenging societal norms about marriage and fidelity.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Indian cinema took a more explicit approach to erotic themes. Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) was one of the first mainstream Indian films to explicitly depict a lesbian relationship. Despite facing severe backlash and protests, it sparked crucial conversations about LGBTQ+ rights in India. In recent years, films have continued to challenge societal norms. Margarita with a Straw (2015) stars Kalki Koechlin as a woman with cerebral palsy exploring her sexuality, including a same-sex relationship, and was praised for its sensitive portrayal of disability and bisexuality. Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016), directed by Alankrita Shrivastava, tells the stories of four women seeking freedom and sexual liberation, faced censorship issues but garnered praise for its bold storytelling and candid depiction of female desire.

The movie Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020) tackles same-sex relationships within a conservative Indian society, with Ayushmann Khurrana’s character fighting for the acceptance of his romantic relationship with another man, challenging traditional norms and advocating for the right to love freely regardless of gender. The film’s portrayal of a gay couple in mainstream Bollywood played a crucial role in normalising LGBTQ relationships and promoting societal acceptance. Similarly, Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui (2021) sees Khurrana’s character fall in love with a transgender woman, played by Vaani Kapoor. The film explores themes of gender identity and acceptance, and advocates for the right to love beyond conventional gender norms. It promotes empathy and understanding of transgender issues, contributing significantly to the conversation about gender identity and sexual freedom in Indian cinema.

Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) was one of the first mainstream Indian films to explicitly depict a lesbian relationship. Despite facing severe backlash and protests, it sparked crucial conversations about LGBTQ+ rights in India

Badhaai Do (2022) features Rajkummar Rao as a gay police officer in a lavender marriage with a lesbian woman, highlighting LGBTQ struggles in India. Similarly, Ek Ladki ko Dekha toh Aisa Laga (2019) stars Sonam Kapoor as a woman grappling with her sexuality and her family’s expectations. The film emphasises self-acceptance and the right to love freely. All these recent films contribute greatly to the dialogue on sexual freedom in India, challenging societal norms, promoting acceptance, and advocating for the rights of LGBTQ individuals to love and live openly. While the West and the Scandinavian societies post-1960s acquired a great deal of sexual freedom, in India the picture is completely different. Caste, class, rural, and urban settings play an important role in the access to sexual freedoms.

It is only with the millennials and that too in urban metropolitan cities that women have finally got their agency. Due to travel, education and economic empowerment, they are taking the lead and choosing their sexual partners.

The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) regulates the content of films in India. Scenes depicting sexual acts, nudity, or even passionate kissing are often cut or heavily edited. This censorship extends to other forms of media, including television and online content.

Society tends to normalise male sexual exploration but harshly judges women for expressing similar desires, reinforcing gender inequalities and limiting women’s freedom. Women are frequently judged on their virginity and sexual history, with notions of ‘purity’ and ‘chastity’ affecting their perceived value and marriage prospects.

A character that stood out to me from the ancient texts was Kunti, the mother of Pandavas, who had the boon to bear children and yet retain her chastity and virginity. The emphasis on chastity and virginity restricts women’s bodily autonomy, imposing strict control and surveillance. This cultural pressure causes significant psychological stress, including anxiety and depression, for those who deviate from norms. Additionally, the double standards in sexual behaviour, where men face less scrutiny, perpetuates gender inequality and reinforces patriarchal norms. Women’s educational and career opportunities are also hindered by early marriage and the expectation to prioritise chastity and family honour over personal ambitions, further limits their potential and contributes to ongoing gender disparities.

In an indigenous society, I find a well thought out system. In the ‘Ghotuls’ (tribal hut) in Bastar, Madhya Pradesh, boys and girls can cohabit together for a week till they decide to make their cohabitation permanent. There is complete sexual equality, and the community has its own inbuilt structure, which has its own checks and balances. Only the young who intend to form long-term relationships are allowed into the Ghotuls. It is not a free space for wild orgies.

The other example is the Ho tribe from Jharkhand, where no such limitations on sexuality exist. In this tribe, homosexual men are called “Kothi Panthis,” and homosexuality has been acceptable for years with no stigma attached to it. Ho tribe is one of the major tribes of the state, but Jharkhand still has no welfare board to implement policies for the LGBTQ community.

Patriarchy in India controls women’s choices, including their sexual and reproductive rights, through practices like early marriage and restrictions on movement. Cultural narratives promote modesty and submissiveness in women, deeming assertive expressions of female sexuality inappropriate. This societal framework fosters shame and stigma, with sex rarely discussed openly, perpetuating ignorance and myths about sexuality and health. Such stigma can lead to mental health issues, especially for women who feel unable to express their desires and identities. Additionally, the prevalence of sexual violence including harassment, assault, and rape— significantly deters women’s freedom of sexual expression.

Despite existing laws, weak enforcement and victim stigmatisation discourage women from asserting their rights. Furthermore, sex education is often either non-existent or inadequately covered in Indian schools, focusing on abstinence rather than comprehensive information about contraception, consent, and sexual health. Efforts to improve sex education face resistance from various societal sectors concerned with potential moral decline. Honour killings are still practised in Rajasthan, Haryana, parts of Uttar Pradesh and even West Bengal, where the zamindari culture is still evident, and the status of many women is still abysmal.

At one level, women are worshipped, but most women still do not have agency. Manusmriti also known as the Manava dharmasastra is a highly contested document that offers an inconsistent and internally conflicting perspective on women’s rights, says Flavia Agnes, a Mumbai-based women’s rights lawyer.

Two specific shlokas from Manusmriti present the status of Indian women:

“Where women are honoured, divinity blossoms there, and wherever women are dishonoured, all action no matter how noble it may be, remains unfruitful.”

And in the same breath, Manusmriti also states that “as a girl, she should obey and seek the protection of her father, as a young woman her husband, and as a widow her son; and that a woman as a wife should be considered as a goddess.”

This contrarian approach is symptomatic of the present status of sexual freedom which confronts the women of India.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

Gukesh’s Win Over Carlsen Has the Fandom Spinning V Shoba

Mothers and Monsters Kaveree Bamzai

Nimrat Returns to Spyland Kaveree Bamzai