Behemoths at the Gate

ELEPHANTS ARE taking to the streets across the country. In Mumbai, a hundred and one gaudily painted works of art, each the size of a tubby pachyderm calf, have taken the city by storm. Very soon, larger, more audacious elephant representations will be walking the evergreen forests of Kerala, the tea gardens of Assam and the Doon valley of Uttarakhand. Come August, and the capital of India will be besieged by elephants. Not live ones, but creations of the human mind and hands, representing their cause. What is drawing these elephants into town? Why are the behemoths gathering in full strength and what trunk call are they playing out? The answer lies in a migration of elephants perhaps three- and-a-half million years ago. That was approximately when the first elephant appeared in India. Having originated in the Al Fayyum swamps of Egypt some seven million years ago, the ancestor of the Asian elephant was pushed out of its homeland by the evolution of the African elephant. That elephantoid, much like early man, wandered the steppes of Central Asia, one line exploring primeval Europe as the mammoth and the other exploring the New World as the mastodon. Some 10,000 years ago, both the mastodon and the mammoth went extinct as climate change and newer evolutionary forms rendered them redundant. Much before that, around three million years ago, one population that had migrated to Central Asia crossed the Khyber and found its way into India. The Indian forms at that time were possibly animals called Elephas planifrons and Elephas hydrusicus. About 250,000 years ago, before the evolution of Homo sapiens had happened in Africa, this branch of elephantoids produced yet another version—with a high-domed forehead, tusks only adorning males, a slightly shorter, stockier disposition and an inclination to form matriarchal herds of highly social, kin-bonded family units. This, Elephas maximus, the Indian Gajah, Haathi or Yaanai has remained relatively unchanged to this day as the Asian elephant, ranging from the Shivalik hills of north-western India to Vietnam in the east and Sumatra in the South.

In India, the elephant turned out to be a holy beast. In Matanga Lila of Nilakantha, an ancient Hindu treatise on elephant sport (could range from over two hundred years old to perhaps even a thousand years), the 'creation of elephants was holy, and for the profit of sacrifice to the gods, and especially for the welfare of kings. Therefore it is clear elephants must be zealously tended. The (Cosmic) egg from which the creation of the sun took place—the Unborn (Creator) took solemnly in his two hands, the two gleaming half shells of that egg, exhibited (to him) by the Brahmanical sages, and chanted seven samans at once. Thereupon (from one shell) the elephant Airavata was born, and seven (other) noble elephants (i.e. the eight elephants of the quarters or regions) were severally born through the chanting'. While the elephant itself was given such holy origins, the elephant-headed god Ganesha was a creation of the Gupta period. Born out of Vinayaka, Vighna Karta or the 'creator of obstacles' (the supposedly malevolent ganas of Lord Shiva, according to one account), Ganesha started being worshipped as Vighna Harta or the 'remover of obstacles'. Was the elephant an obstacle to primeval man, and just as fire and lightning and water were feared and worshipped, was the elephant an early wildlife conflict species worshipped out of fear? Was the single-tusked Vighna Harta himself the obstacle to early man such as to inspire fear and cause the beginnings of holiness? Was this then transformed into the pot-bellied benevolent remover of obstacles when caught and tamed by ancient kings? To understand the concept of Ganesha, one has to understand the biology of the species.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

An elephant can be defined by four simple words; Big, Intelligent, Social, Nomad. They are Big and are so classified biologically as Mega-herbivores. They are Intelligent, with a brain capacity that rivals great apes and cetaceans and attributes of memory, consciousness and cognition that have caused many scientists to compare them to humans. If our arrogance as a super species did not intervene or the physical attributes of a trunk did not befuddle, we could have granted them personhood. I, personally, call them near-persons; so close are they to us in so many mental attributes. They are extremely Social and matriarchal to boot. And because of being Big, they are also Nomads. If they were not, they would quickly eat themselves out of a home. This is the sad reality in much of southern Africa where elephants confined to national parks are eating themselves out of a sustainable home. Then wildlife managers are called in to cull the animals as there are 'too many elephants'. But the problem has been caused not by the elephants themselves but largely by man. By enclosing them in small spaces either by fencing them in, as in southern Africa, or hemming them in with large human populations, as in South Asia, we have stopped the traditional migratory paths of history's greatest nomad. When the British first visited India, elephant paths provided them with the most stable gradient in the hills to cut their roads. A brilliant engineering feat, no doubt, but a death knell for the elephants. As the years rolled by, elephants have been dispossessed of most of their way of reaching other habitats from the one they have fed on, so that they get access to further feeding areas while the ones they leave behind regenerate. With this happening, conflict with man has reached epic proportions. While conflict has been documented from historical times, never has it reached a stage where more than 400 people and 200 elephants are dying annually in the carnage. Never have tar balls of fire been thrown so callously at elephants, once revered as near-gods. Never have so many spear and gunshot injuries been treated at rescue centres across the country. And never has public sentiment turned so against the animals that a young wastrel could scrawl in chalk on the carcass of a poached elephant, 'Paddy Thief! Osama Bin Laden!' The conversion of Vighneswara to Ganesha had taken centuries. It now has taken only a few years for Ganesha to be transformed into Osama, bringing the National Heritage Animal to its knees. Now is the time to act.

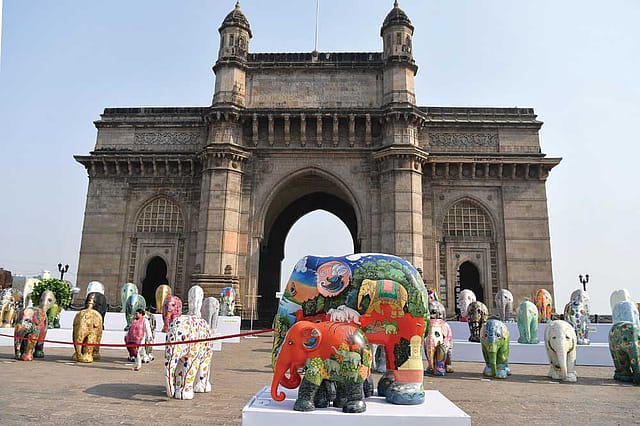

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO, realising the plight of elephants, I launched what has come to be known as the Right of Passage project to secure elephant corridors. A starting point was to win back the hearts of people. Thus was Gaj Yatra born, a tour-de- triomphe of the pachyderms touring India along traditional corridors to spread a message of elephantine love. The tour conceptualised elephant-sized art pieces that would assemble at massive public events in every state that has elephants and then in a massive Gaj Mahotsav in Delhi in August. In a lead up to this, the UK charity Elephant Family, presided over by Prince Charles and Camilla, also had a massive Elephant Parade in Mumbai. Using 101 identical white elephant bases painted by artists as varied as Christian Louboutin to Rohit Bal, from Sabyasachi to Anita Dongre, it took the city by storm earlier this year. Even Amitabh Bachchan and Shah Rukh Khan put finishing touches to some elephants. Vasundhara Raje, the Chief Minister of Rajasthan, lent her name to an elephant. The glitterati of Mumbai turned up and bid for the elephants. The money raised in the auctions would contribute to securing elephant corridors.

The Gaj Yatra meanwhile started up in Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh in tribal festivals. One elephant was created out of used TV screens (an ode to e-waste), another made of bronze, a third out of banana leaves. Indian artisans at their talented best were creating elephants across the country. Renowned art curator Alka Pande is masterminding this effort. Another art aficionado and lover of elephants, Ina Puri, has been curating two dozen eminent painters to depict the National Heritage Animal on canvas. Children were gathering in large numbers and creating clay elephants taken from the very mud the elephants were demanding for passage rights. Spearheaded by Wildlife Trust of India, Ministry of Environment and Forests, the UN Environment Programme and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, this Indian march of the elephants will reach its zenith between the International Elephant Day on August 12th and Independence Day on the 15th in Delhi.

What remains to be seen is whether the cry of the elephants reaches—through the art, music and pantomime— the ears of those who have the power to relieve the animal of its shackles. The Railway Ministry recently stopped a rail line from cutting across an elephant corridor. The Environment Ministry has sent out a notification requiring new infrastructure projects to build in measures like overpasses or underpasses for elephants and other wildlife to pass through. A Supreme Court order was recently implemented in Assam to demolish a wall that was impairing elephant movement. Is this the beginning of change for elephants? Only time will tell. Meanwhile, as celebrated by Kalidasa in Abhijnana shakuntalam, the bull elephant still stalks the edges of human civilisation, himself terrified and impeded but also in turn terrifying and impeding.

One tusk is splintered by a cruel blow

Against a blocking tree; his gait is slow,

For countless fettering vines impede and cling;

He puts the deer to flight; some evil thing

He seems, that comes our peaceful life to mar

Fleeing in terror from the royal car.