The Politics of Masks

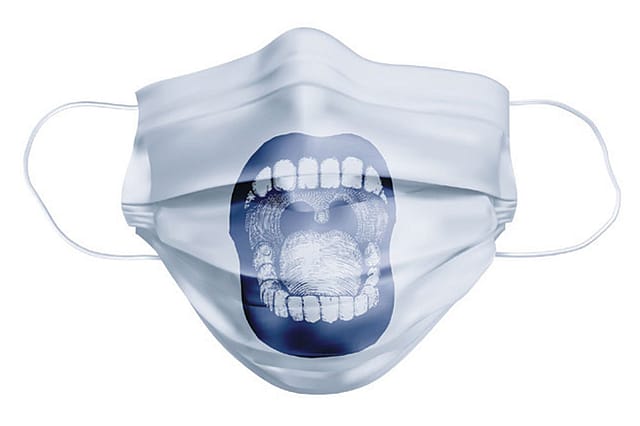

IT'S EVERYTHING NOW. It's what sets you apart. It's the mark of responsible living, and a filtered defence against death. It's a piece of cloth that conveys individual duty and civic solidarity, no matter it has denied us the many givens of social as well as personal intimacies of communication. It's a talismanic sign of our pandemic times.

There is more to the mask.

Elsewhere, it's a political statement. Its absence is a declaration of freedom, and a repudiation of enforcement. Defying science and common sense, the intentionally maskless makes an argument for the autonomy of choice, and intends to trade it for ideological gains.

It's a choice made to subvert consensus, and pandemics, like wars and calamities, create a social order built on fear and expertise. To break it is to put your right, even if it makes a bad choice between life and death, before shared knowledge. It is to be self-consciously stupid instead of being robotically obliging.

Is it the choice of the false libertarian?

The sovereignty of 'me' rejects the all-knowing state, and whose voice usually comes through the bureaucracy of behavioural code. The libertarian is a fundamentalist, a denier comforted by his own faith. The inviolability of his faith is his ultimate security in a world of stifling agents of change. The utilitarianism of change, he believes, asks for a price from the individual. He has been asked to pay with his faith for the promise of security. For health lately, he protests.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

The mask, or the absence of it on faces in a shopping queue or in a political rally, becomes a statement about how ideologies divide a world when it is most vulnerable. When the coronavirus began to spread and kill, some of the freest democracies were reluctant to curtail individual movement—or control it. Even experts were of two minds then—to close or not to close the pub. And no expert was sure about how a mask could minimise the transmission of the virus.

That was a time when the politician was more authoritative than the expert. We saw all the types then, facing up to an inchoate threat. The liberal in the classical mould, now most likely a conservative in a Western democracy, was reluctant to be an alarmist, and averse to fight an illness by retreating from individual freedom. This politician relented only when fear replaced cynicism.

There was another type: the authoritarian who saw in the viral adversity a political opportunity. Already the sole arbiter of freedom, he now rearmed himself as the saviour with all the knowledge—and demanded more from the people. When science was uncertain, politics knew what exactly was it seeking. It feasted on fear.

Then there was the one who realised that leadership did not mean the bravado of denials or an exploitation of fear. This one respected science and expertise, and to a greater extent succeeded in containing the virus. Between the freedom that was certain to increase deaths and the control that only strengthened the strongman further, this was the option based on the decencies and responsibilities of governance.

Any of these three versions of leadership has not fully contained the virus, but their politics decided the degree of containment. The wisest of them did not get trapped in the rhetorical choice between saving lives and saving livelihoods. It was an alliterating falsity that came handy to the Left and the Right. It made the lockdown a dispute between the compassionate Left—let's remain indoors till the virus goes away; and the realistic Right—let's get on with life. Today, the dispute is over opening schools and bars. The dispute is political because it subordinates freedom to ideology. It seeks expertise only for political ends.

When the pandemic peaked, the most conspicuous talisman of the times became an incendiary political item. The world's most powerful politician refused to wear a mask because he thought it was a nuisance perpetrated by the scientific establishment. He stood by his personal choice, as a defiant bad example. When he began to acknowledge its usefulness, he regained a bit of his lost humanity in the eyes of his critics; and when he finally wore one, it was a global headline of how he became a human for a day.

It is as if the mask defines the man, but it doesn't conceal or control the transmission of the ideological virus. Once the word denoted the unspecified, even the unreal. It kept truth out of sight. One evening in the neighbourhood, we may all look like escapees from a comic book. The odd man out, maskless and dangerous, is the last bad example of freedom, and still, somewhere, someone is ready with an argument that makes him a necessary political symbol. It is a paradox of the pandemic that it takes a mask to reveal our intentions—political or individual.