The House of Jaswant Singh

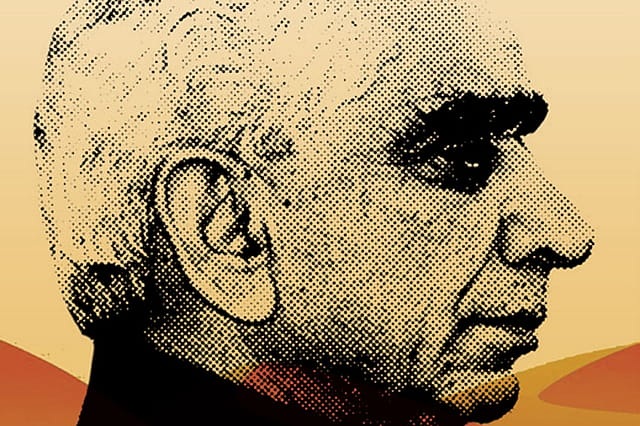

HONOUR IS THE word that recurs in the self-expressions of Jaswant Singh. A Call to Honour—a nod to his idol Charles de Gaulle—is what he calls his memoirs, in which a dutiful nationalist strikes a fine balance between ancestral morality and territorial affinity. It was "a call that had to be honoured", whether it was the formation of India's first right-wing government headed by Atal Bihari Vajpayee or managing the aftermath of the Pokhran nuclear tests of 1998 or breaking out of the behavioural traps of Third Worldism and anti-Americanism. He served as a "caravaneer"—he could not resist a resonant archaism borrowed from the desert—of a moment in India's life that required "re-routing from the unrealistic idealism of a past that was long gone to the needed realism of a new, demanding and an impatient age, between the fixities of a handed-down wisdom and the needed dualism of our times." When I met him in his office in South Block in 2000, he was the foreign minister who loved to quote the Gita to explain the nature of his job. It is rooted in smriti, he told me, the meaning of which can't be fully captured by the English word 'memory', and, in the Gita, it appears in the first canto when Krishna counsels Arjuna. Seventeen cantos later, Arjuna tells Krishna that he has regained his smriti. "It is the function of foreign policy to enable the nation to regain its national smriti," he said in that measured baritone. It was a call that had to be honoured.

Reading him, one realises that he had the first intimations of that call when he grew up in the House—that is what he calls it, always with a Capital H—in the Rajasthani village of Jasol, in Mallani, today's Barmer. He failed to represent Barmer in Lok Sabha and the defeat would remain a bitter aftertaste in his political life that began as a national calling and ended as a personal humiliation. He would never recover. The House from where he inherited the moral grammar of Mallani was "built by time". The House, a work in progress, signified "age and ancientness", always echoing "a stone-mason's hammer and chisel". Keep moving, keep building—that was the House ethos. "And wherever we went, there was just one injunction that accompanied us, as a task and responsibility: 'It is the name of this House…Remember!'" Lest-I-forget—and it alone determined the pace of the remarkable journey of an officer, a gentleman, an administrator, and, in the end, a lone man whose sighs and sorrows went unnoticed in the other House that shaped his political life.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The inflection points in the journey were exhilarating as well as demoralising; they were also a nationalist's hard choices. It was exhilarating when he was Prime Minister Vajpayee's chosen man to bring India from the residual fog of the Cold War to the sunset of anti-Americanism. As India's interlocutor in a transformative period, he enjoyed every moment of it, making a few American friends along the way. As our uber diplomat JN Dixit once told me, he was "India's first public-school educated, anglicised foreign minister after Nehru." The refinement helped when India needed a language freed from ideology. Then there was Kandahar—the hijacking of Indian Airlines flight IC-814 and the hostage exchange. It was painful pragmatism that took him to Kandahar. For some, it was surrender to terror. He was the man in the sordid picture, and the picture never revealed what raged within him.

And then came the misread book, Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence, which angered some nationalists because he argued that "Jinnah did not so much win Pakistan as the Congress leaders Nehru and Patel finally conceded Pakistan to Jinnah, with the British acting as an ever helpful midwife." The Patel part was blasphemy. He did not exonerate Jinnah. The book traced the evolution of a man who began as a national constitutionalist, peaked as a Muslim separatist and ended up as the creator of Pakistan and a rhetorical secularist who would be defeated by his own creation. Singh was the second Hindu nationalist haunted by the Quaid-i-Azam. He would be banished for thought crime. He was not for recanting; honour didn't allow him. Public life for him did not mean compromising on the moral inheritance from the House in Jasol. He would return to the House in his own metaphorical ways, most memorably as a writer, and even as a solitary soldier who hoped his party would indulge him for once. The battles never ended.

I remember that evening in Jaisalmer many summers ago. Relaxing after a hard day's campaigning, he pointed to the sandy vastness and reminisced about a childhood enriched by the mystic desert. Maybe that howling expansiveness of freedom prepared him for the harsher realisations of

a life far from the House of Jasol.