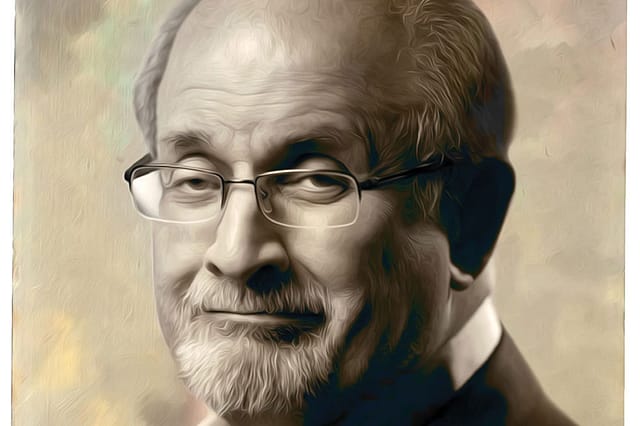

Salman Rushdie: “It’s the first time I’ve allowed myself to write a self-conscious fiction about the making of a fiction”

SOME NOVELISTS ARE great explainers, interventionists in their own story, demystifying the hidden anagrams and casual allusions that we missed in their art. As they go along, the stories themselves become a meditation on storytelling—a tribute, a temptation or a tantalising pause in the text.

Milan Kundera, to cite an obvious example, wrote three books on the art of the novel itself—the art of his literary genealogy. They are memorial services and re-readings, reflections on what he owes and the burden of his indebtedness. In the second, Testaments Betrayed, he writes about how the homeland of the novel, Europe, has let its art down, and how it has taken refuge in the tropics, in the novels of writers like Salman Rushdie. Rabelais doesn't laugh from Europe any longer.

Rushdie may not have written books on the art of the novel, but, lately, the art of his novels carries within it the sighs and ecstasies of a writer. The writer becomes the story; the story, a perpetual movement of freedom. For writers who had the misfortune of living within the horrors of exile—a place where time rusts—the story is what makes displacement bearable, the metaphor is what defeats the lies of the state. Today you don't need an Ayatollah, or the book burners of Bradford, to threaten the Imagination. The Book is not the only custodian of the Truth. The politics of alternative realities have gone mainstream, and it's as if you have been condemned to the vulgarity of reality television. The story is under pressure to seek its own realities. The story is breaking out of the old deceptions of allegories and pastiches to become intimate, urgent and direct. And Rushdie is one writer who never gets tired of telling his indebtedness to the story, to the journey.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It began with Cervantes, who could not keep himself out of his story of fiction's first and last knight, Don Quixote of La Mancha. Cervantes, a war-scarred playwright of moderate success, was rewriting the novel itself, with overwhelming self-consciousness. He was debunker as well as rebuilder of an art form, challenging its cosy assumptions and silly adornments. In telling the story of "the most chaste lover and most valiant knight" and his squire in whom he has "summarised all the squirely wit and charm scattered throughout the great mass of inane books of chivalry," he had placed himself in the imagined world as explainer, participant and the only reliable remnant of reality. He had done so on behalf of the future writer.

When Rushdie names his fourteenth novel Quichotte—another pronunciation of Quixote—it doesn't require much of an explanation. The modern novelist's indebtedness to Cervantes needs no acknowledgement. It's there for us to read and reread, certainly in the formidable oeuvre of Rushdie, a master of cross-cultural picaresque. In Quichotte ('Rushdie's Quest', August 30th, 2019), the adventure of another lover and his squire shows that the picaresque remains the same even as the backdrop shifts. In my telephone conversation with Rushdie last week, he tells me that the indebtedness to the father of the modern novel is obvious: "All writers owe him a lot. We owe him complexity, digressions, stories within stories, and the metamorphic possibilities of the novel as a journey. We also owe him modernity. He got there four centuries ago." Rushdie read Don Quixote when he was 20, as a student at Cambridge.

Three years ago, he was a speaker at the celebrations of the great Spaniard's four hundredth anniversary. Still, the provenance of Quichotte is less fictional. "The novel was born as a non-fiction idea," he tells me, "a real road trip across America I might make with one of my sons. But it quickly transformed into make-believe."

Does it happen often, the story changing the form?

Improvisations along the way?

"Lately, maybe. I have become more and more willing to allow the work to be discovered in the act of creation. One has to be first something like a jazz musician improvising the music into being, and then one's own sternest critic to see if what you have written should be kept or not."

A novel about the art of the novel itself?

"It's the first time I've allowed myself to write a self-conscious fiction about the making of a fiction. The two storylines, the story of the creator and the thing created, are designed to illuminate each other and, slowly, to merge."

Quichotte is a cross-pollination of imagination. The eponymous hero is imagined by a spy novelist of moderate success in his bid to reinvent himself, and who in turn is born out of someone else's imagination. And Sancho, the perfect squire and the son unborn, is a half-imagined being, and whose lover, 'the Beautiful in Beautiful', is a figment of…What's going on here, everyone is imagining the other?

"Yes, it's what we all do: we use our imaginations to understand one another."

It seems a novelist can't trust reality; he has to create his own.

"Reality has become so contested, fragmented and politicised that maybe only the imagined world can be coherent."

In Quichotte, the real, and the most coherent, is the quest, as eventful and as tragi-comic as the one undertaken by Cervantes' knight. The quest is primordial. As Rushdie tells me, "The quest as a theme predates the novel, going all the way back to Fariduddin Attar, John Bunyan and Homer. Quichotte's quest is not only for the love that he says is his Grail, but also to become worthy of that Grail. This quest involves learning, testing, growing."

For Sancho, the quest is both poignant and phantasmagorical. Rushdie tells me that some early readers of the novel too found Sancho precious. Even in the original, as Harold Bloom writes in his introduction to the brilliant new translation by Edith Grossman, Sancho gets great admirers like Kafka, 'a pupil of Cervantes'. In Bloom's words, 'To Kafka, Don Quixote was Sancho Panza's daemon or genius, projected by the shrewd Sancho into a book of adventure unto death. [According to Kafka], the authentic object of the Knight's quest is Sancho Panza himself.' Rushdie too is a fan. He tells me: "I became immensely fond of Sancho, of his obstreperousness, his aggressive adolescence, and at the same time his immense desire to be, to become: like Pinocchio, to become a real, live boy. He is the character most wedded to the beauty of life itself."

The reality Sancho and his knight confront in America is hardly beautiful. What they face is the street theatre of hate. In this America, a White lady asks them, "where are your turbans and beards?" Not just America, England too has changed. "For so long thought to be the most pragmatic and commonsensical of peoples," the English are "presently torn asunder by a wild, nostalgic decision about their future," as the narrator of Quichotte says. India is also a different place; he still holds on to the sepia version from memory. All three are places integral to his evolution as a writer, who now lives in New York. Is he disappointed by the change? "They are all in love with fantasies of the past, and that illusory love greatly damages the present," Rushdie tells me. In Quichotte, fantasy pervades the present too. We are introduced to Italian-speaking crickets and guns with a conscience, not to speak of those mastodons. In Quichotte, the real draws its magic from spy novels and science fiction. What's at work here? "For a long time," Rushdie tells me, "when I was a teenager and devouring fantasy and science fiction, I wanted to be a sci-fi writer. Later, I thought I might be a spy novelist. In this, I have been able to gratify both urges." He reduces the distance between autofiction and metafiction in the process. Lest I missed some private jokes and self-references in the stories within stories, he tells me that Miss Salma R, the Indian-American television star Quichotte seeks, is a play on Salman Rushdie—and that "spacious apartment above a restaurant" in Notting Hill in West London is the apartment where Rushdie lived. In the novel, the Author's sister lives there. Did I miss anything else? "I told you most."

A Rushdie novel is a big tent. It can accommodate everything, everyone—and every argument. He is closer to the classical Russian novel—of the big, shapeless novel of whirling ideas and crazy characters—than to bespoke fiction shaped by creative writing classes.

(He is aware that some reviewers don't review his books. "They review me." They review Rushdie the famous public figure. "And they are people who have no idea about the life I live.") Quichotte too swells, faster than before, doesn't it? "Well, I've written panoramic books before, but what I'm happy about in Quichotte is the 'lightness' and 'swiftness', to quote Italo Calvino's recommended literary virtues, with which the tale is told, a thousand pages of story told in just 400." Shall I say a tale about the end of the world itself? "Yes, as madmen cry on the streets of our cities, the end of the world is nigh, prepare to meet thy doom."