The Afterlives of Stitches

Celebrating the relationship between Adip Dutta and late artist Meera Mukherjee

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

12 Feb, 2021

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

12 Feb, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Afterlife1.jpg)

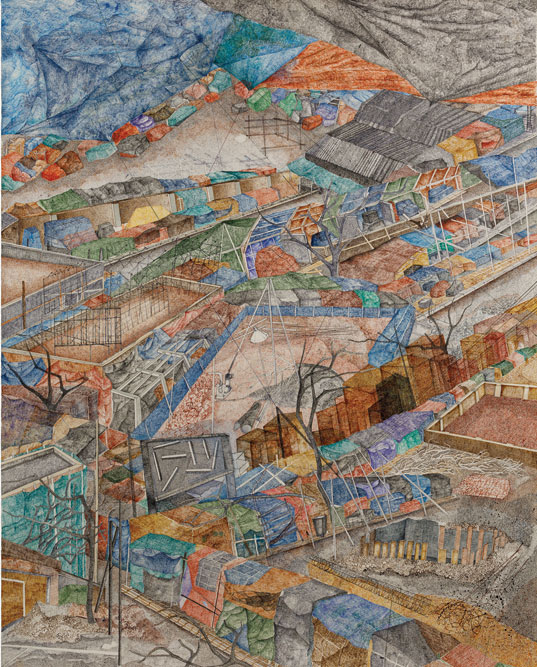

Topographic Specimens

AS I WAS gleaning the rich metaphorical connotations inherent in the titular ‘Nestled’, an ongoing staged conversation between Adip Dutta’s meticulous sculptures and ink drawings and Meera Mukherjee’s visionary exploration of Kantha, I felt confronted by its audacity. Experimenter, the host gallery, was offering viewers a context within which to re-locate the artistic practice of Dutta—one of its star artists. The dialogic nature of the show seemed not only obvious, but its logic was also beyond reproach. For anybody who knows the 1970-born Dutta—a member of the Faculty of Visual Arts at Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata—is undoubtedly aware of how influenced he remains by Mukherjee, who was born in 1923 and died in 1998.

This ‘influence’ is unconventional and non-institutional. The most animated proof of it is anecdotal. I can testify to my own engagements with Dutta over a four-year period of conversations through my visits to his Kolkata-based studio. There isn’t a single transcript in which he hasn’t mentioned Mukherjee either as a point of reference or departure. I have often even envied the tenderness with which he speaks about her life, frequently reminding me of how ‘remarkable’ she was, and how foundational their friendship had been to the evolution of his artistic self and identity, to the extent that I have wondered if she had come to be an extension of him; as if he was privileged with being able to access not only his own artistic subjectivity, but hers, too. “What happens with people who you’ve lost is you create some kind of window in that person’s absence… from time to time you open it to communicate… it’s an imaginary conversation,” Dutta tells me over a phone call. Even though we are currently separated by continents and aren’t using video, I have little difficulty imagining his face aglow as he reminisces, always seeming slightly frustrated by his inarticulacy. One can perceive how his memories of Mukherjee are seamless. “Everybody knows that she was such a remarkable person. There’s so much I remember instantly when I start talking about her.”

When he does begin he usually struggles to coherently frame the intellectual and artistic intimacy that marked their relationship. I find myself frequently so invested in the anecdotal onslaught, I struggle to anchor the narrative. Dutta met with Mukherjee on an almost daily basis for over 17 years. He vividly remembers her beautiful two-room flat with its gleaming red floor in a colonial building with cast iron railings. He has repeatedly told me how he was in his formative years, and that he was among very few people with whom she interacted so regularly. She generally reserved only one day a week—Saturday—for social engagements. When he was around 14 or 15, Dutta began to frequent the workshop of the same traditional idol maker Mukherjee would visit. “She would come from time to time and we exchanged glances,” he tells me.

Eventually, they exchanged views, too. Some of the members of the craftsman’s team assisted Mukherjee in casting her sculptures at her own workshop in Elaichi in Narendrapur. Later, a mutual friend took Dutta to Mukherjee’s studio. “I don’t know if she realised… now when I look back I think in these terms… I had also gone with my idiosyncrasies. As a child there was a self which was neither accepted by others in one way, and a self which was also not ready to accept the self… What I’m trying to say is that there was a state of confusion, of rejection… I’d gone to her at that point,” Dutta tells me. “Later, from the little stories I heard from her, about her, from her eldest sister, from Nirmal Babu, then the nephew, with whom I connected later… I felt that there was a sense of torture that she, too, experienced. It was not easy for a middle-class Bengali woman in the ’40s to come out of her family. She was driven out of the house, she claimed… It was such a beautiful place for me to visit, and I would spend hours, from 4.30PM onwards, and I’d be back in the evening when I should have been doing my homework and I’d get scolded at home.”

MUKHERJEE FORMALLY studied art in leading institutions in Kolkata, New Delhi and Munich. However, the core of her practice seems to have been formed extra-institutionally. In her diary she has recounted learning to make dolls from her grandmother, and inheriting from her mother a flair for Alpana, a Bengali version of floor patterning. After returning from Munich, she set out on a quest to study indigenous crafts and wrote a moving and laboured thesis on metal casting in India, thanks to a grant from the Archaeological Survey of India. The 470-plus-page dissertation, the culmination of her travels in the mid-1960s, reveals her deep immersion in recording the caste and tribal lineages of the metal craftspeople, how they came to be initiated into the trade through family legacies, accompanied by a profound investigation into their techniques, complete with illustrations. In her introduction she enumerates some of the challenges she encountered, like lack of transportation. ‘Large distances had to be covered on foot in hilly jungle contries (sic) not served by any form of public transportation. Mud flats during the monsoons and sandy wastes has to be crossed on bullock carts: time wasted in reaching a place, which promised useful and interesting information, cut into daylight hours, and where there was no place whatsoever for a night halt, interviews had to be snappy, observation brief.’

The scope and extent of this undertaking must have indelibly impacted her practice, as did her informal training as an apprentice for traditional Dhokra sculptors of Bastar in Chhattisgarh. From them she had learned first-hand how to manipulate the lost wax technique of bronze casting. Dutta points out that what many sometimes invalidate as decorative elements in her sculptures are actually her innovations with using rolled wax to create surface textures that are tangibly manifest in the final bronze outcome, offering the suggestion of tactility and organic form.

Everybody knows that Meera Mukherjee was such a remarkable person. There’s so much I remember instantly when I start talking about her, says Adip Dutta

This observation by Dutta about Mukherjee’s practice finds firm footing in Nestled. It serves as the technical metaphor that grounds both their practice. Dutta had witnessed first-hand Mukherjee’s deliberations with the surfaces of her sculptures, her dedication to making visible the constituting elements; like weld marks, or wax rolls. He interprets them as sutures, of sorts, part of the same language she had been evolving through her sculptural engagement with the medium of Kantha, grounded in the same spirit of community-centric art-making that distinguished her artistic practice from many of her contemporaries. Nandini Ghosh elaborates on this sensibility that Mukherjee internalised from her life-long collaborations with indigenous Indian craftspeople. ‘In Meera Mukherjee’s opinion, an artist primarily aspires for recognition and status as an ‘artist; an artisan aspires to link life and art into one inseparable entity; this distinction was an essential and integral part of Meera Mukherjee’s vision, and form the basis of her conviction,’ she has written in a monograph on Mukherjee published by Mapin.

In Nestled, we are presented with the legacy of Mukherjee’s prescient collaborations with Kantha embroiderers and their children. As a way of offering a possible income for young women in Elaichigram and Nolgarhat, the site of her workshop where she cast her sculptures, Mukherjee began to serve as a mediator, encouraging the children to make drawings, which their mothers then converted into Kanthas, mostly single-layered and made for decorative purposes, without functionality as the premise. Mukherjee commissioned the piece, paid the women, sold the works, and offered the earnings to the women, who eventually formed a cooperative with a bank account. In a way she initiated an informal non-institutional educational framework that was matrilineally perpetuated. Many of these Kantha works currently exist as a significant part of important private collections. Dutta had received a few from Mukherjee, which are part of the display at the ongoing show. This entire project initiated by Mukherjee and sustained over years was part of his dissertation, titled ‘From Child Art to Stitched Painting—A Creative Journey,’ which attests to the service Dutta performed in bringing this non-institution-based learning methodology within the purview of institutional memory.

Some of the pieces were made into carpets by Abu Taher, a carpet weaver from North Bengal, one excellent instance of which is also on display.

This tendency to make visible structures and connections that often remain outside the purview of art historical discourse and that form the basis of artisanal subjectivity is one of many proclivities Dutta inherited from Mukherjee. Nestled celebrates the spirit of this heritage. Mukherjee’s interventions with Kantha through her mediations with the women who created them and the children who made the art that formed the foreground made of it a playful, imaginative, and collective enterprise, while tapping into its proudly decorative core and evolving an economic system that helped empower the makers.

Adip Dutta points out that what many sometimes invalidate as decorative elements in Meera Mukhjerjee’s sculptures are actually her innovations

Dutta’s own work is never eclipsed by Mukherjee’s excerpted contributions. In fact, Nestled is so tenderly put together, using clever modes of display, like the open-ended wooden shelf-like structure, that it allows room for the visual conversation to transpire and percolate. The Kantha stitches resonate in Dutta’s ink drawings through his elaborate and painstaking brush strokes. The centrepiece is Vestige, his bronze study of a fallen tree, a work that was being processed during my studio visit in February 2020, when Dutta, along with his sculptor-assistants were encasing the dis-membered plaster cast’s interior with red wax. I observed the hollow interior of Dutta’s study of an uprooted tree being layered with hot wax as it was readied for the final casting to be made in bronze. It felt like a visual metaphor for the osmotic nature of Dutta’s relationship with Mukherjee. Nestled makes public some of the vestiges of their conversations, and reveals the many afterlives of Mukherjee’s artisanal legacy. It feels like a triumphant celebration of the brazenly non-canonical. The iconic nature of the ‘nest’ as safe space and playground is evolved through the evocative Kantha stitches, through Dutta’s scrupulous mark-making, through the patinas he arrives at in his Topographical Specimens and his bronze works that are odes to the compositional elegance of collapsible street shops in Kolkata, and his private investigation into tracing erosions and making visible the tension of bound things in Marks. The show delights in the literal and metaphorical equivalence between the intuitive, resourceful gathering integral to nest-making and the practised frugality, inherited intelligences, and nurturing potential of craft traditions. As a feminist viewer, it feels satisfyingly audacious to see a male artist embrace a legacy so avowedly non-canonical, so lovingly indebted to artisanal grace.

(Nestled by Adip Dutta & Meera Mukherjee runs till March 31st, 2021 at Experimenter, Hindustan Road, Kolkata)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Puri Marks Sixth Major Stampede of The Year Open

Under the sunlit skies, in the city of Copernicus Sabin Iqbal

EC uploads Bihar’s 2003 electoral roll to ease document submission Open