She’s Got the Groove

A GROUP OF plainly- dressed women strut ahead. Behind them, stand the concrete pillars of an empty parking garage. At their centre, a short-haired woman wearing a T-shirt dress of Matisse-like print, sings straight at the camera. There's a swag to her gesticulations and at times, a certain goofiness, too. "Pratidina hosa avakaasha, Kanasu kaanu neenu miti iraade aakaasha," she says, shrugging her shoulders. "Every day there is a new opportunity, Dream higher than the sky."

Siri Narayan (known by her stage name, Siri) raps in both English and Kannada. "People haven't seen a woman rapping, especially in Kannada," she says, "so it catches them by surprise." Between the internet and live gigs, Siri's following is growing. Her single, Live It, a bilingual track, has over 2,00,000 views on YouTube and she has already been signed by a label called Azadi Records.

"Social media is a good way for me to promote my work, figure out what my audiences would like to see," Siri explains. From writing her own lyrics, to creating her own beats, to designing and editing her videos, Siri does nearly everything to make and market her music. When asked if the buzz around the film Gully Boy had brought her work attention, she was dismissive. "Gully Boy is mostly about rap from Mumbai…It doesn't resonate with me."

Last IPL season, Siri had been approached by Star Sports Kannada to create a video in support of Royal Challengers Bangalore. The timelines they had proposed were too tight, so the project fell through. This IPL season, Siri decided to continue with what she had written, and self-produced a rousing, predominantly Kannada track in support of the team. Titled RCB Anthem 646, the video was released in early April. Although it has drawn some attention, the response hasn't been ideal, Siri says. "People keep comparing it to my other work even though it isn't my single…it began with a commercial project," she laments, "And it would help if RCB were playing better!"

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Negotiating commercial and commissioned tracks with ones that are more aligned with a personal artistic vision can be a challenge, especially for women rappers. "It is a male-dominated art," Siri says, "We usually come into the picture when someone requires feminism. Honestly, I'd rather not be called a female rapper. Just a rapper."

But Siri believes she has it easier than others as she is one of the few women rappers to be signed by a label. Although she has yet to release a single with the label, she ekes a living through her music. Being asked to rap about topical issues with pre-written lyrics or to sell products through rap seems to be a trend among women rappers. Sofia Ashraf, who has gained attention for her rap take-downs of Dow Chemical and Unilever, says that women rappers constantly have to make choices between commercial, financially lucrative projects and their own politics. "Brands have realised that women are consumers. And brands are trying to sell a product. So they try to leverage what you stand for… I have turned so many projects down," she says.

"I rap so that I can touch people with something that's right in front of them. But now they can see it from a different perspective," says Dee MC

Ashraf, however, doesn't see herself as a rapper exclusively. "Writing has been my first love and first profession. I see myself as a communicator," she stresses. "I create art that is a manifestation of my writing. Rap is one manifestation'. Ashraf, now 32, chanced upon rap in her teen years, when she began writing and rapping lyrics to express herself within the orthodox Muslim environment in which she lived. A devout Muslim back then, she rapped about Islam in a post- 9/11 world, among other issues. After performing in a burqa at a copy-left, anti- establishment event in Chennai called Justice Rocks, she quickly shot to fame as the Burqa Rapper, a moniker that seems to have followed her long after her own ideas and persona changed. But Justice Rocks was a pivotal moment also because it shaped the kind of content Ashraf would address. When Justice Rocks asked her to write about Bhopal, it marked a new direction in her music.

"It was my first tryst with something beyond myself," she says, "It was liberating, enlightening." Since then, Ashraf has rapped on a number of environmental, human rights, and gender issues. "I do believe in art for art's sake," she says, "but there are moments when you wonder what is your role as an artist? And if it can make a difference in people's lives."

With tracks such as Kodaikanal Won't (about Unilever's dumping of mercury in Kodaikanal), I Can't Do Sexy (about female body expectations), and 24 Seconds Breathless Rap (about air pollution), Ashraf is often hailed as an activist rapper. But she insists that isn't the agenda. "I rap about things that mean something to me. Rap is for me almost cathartic…It is as enjoyable for me as it is for the audience…I do have songs in which I explain my story but you can't separate the personal from the political. These are my politics. And for people, it's the political that sticks".

Although Ashraf creates a lot of music and video content for YouTube (including her comic feminist videos under Sista from the South), she performs live too, but at intimate venues. She prefers smaller, rapt audiences. She says she has avoided signing with a label so she can have more freedom to choose projects that she can truly stand behind. "I don't want other people's salaries to be dependent on my choices," she says.

Despite her prominent feminist image, Ashraf consciously shies away from all-women gigs and women's conferences. She felt these were becoming "echo chambers" for her work, so in the last year, she has instead chosen to perform at colleges to engage with a younger audience. Just as she was uncomfortable being typecast as the "burqa rapper", she also finds that big all- women platforms run the risk of tokenism. To be identified as a female rapper rather than simply a "rapper" doesn't sit easy. She released a track Kaam Se Matlab Rakh, which talks of women being identified as female versions of their professions. Yet, she is careful to point out the complexity of these politics. "That track was targeted at an educated middle- class audience. In a place like Mumbai you can say 'kaam se matlab rakh'," she explains. "If I performed in Chandigarh or Chennai, I would happily call myself a female something. I went to an all- women Muslim college, where we didn't see women do anything. We need to give time in these contexts."

"You can't separate the personal from the political. These are my politics. And for people, it's the political that sticks," says Sofia Ashraf

DEEPA UNNIKRISHNAN (or Dee MC), known as the "female rapper in Gully Boy," shares a similar view. "The tokenism does annoy me but I have also gotten used to it. When people call me a 'femcee', I correct them. But if people call me a female rapper, I don't take much offence because it's true—there are so many rappers but only three or four of us are women. I pick my battles." Until two years ago, Dee had to rely on work beyond her music to earn a living. Now, she is able to manage through her several live gigs and commissions.

"I got into hip-hop music through dance," Dee recalls, "But it began to take a toll on my back so I had to stop." Having written poetry since her school years, Dee then gravitated towards the rhythm and music of hip-hop and began rapping in 2012. "The storytelling side of hip-hop made me want to do it. I rap so that I can touch people with something that's right in front of them. But now they can see it from a different perspective." Dee, who raps in English and Hindi, has a distinct style in which she intersperses rapping with singing. She feels that audiences often lose attention with a barrage of words, so she tries to create songs that they can also groove to.

Tracks like Bulletproof and Chaar Logo Ki Baatein nudge at the difficulties of being a female rapper, from social expectations to sexist audience responses. But Dee says it took time for her to feel comfortable rapping about feminist topics. "In the beginning, I didn't want to do it for the sake of trends. But then I realised that I did want to talk about those things…try to challenge set rules and superstitions about women."

"I do have a lot of leverage," Dee confesses, "There are not many female artists so people want you". Unlike Siri and Sofia, Dee has found that she is able to negotiate her own vision with that of commercial projects. "Brands approach me for female-centric things but that's not a negative thing. I am able to earn while talking about the things I want to talk about. When they come in with a script, I rework it in my own way."

But while Dee is commercially successful, she admits that it is tough trying to work as an independent artist. "It's tedious. I need a manager!" she says with a laugh. She doesn't like to dwell on the difficulties of her early career any longer but says that success isn't smooth either. "People know me now but the numbers don't reflect. Write a stupid song and you get so many views. Write something sensible, and hardly anyone sees it."

"I do give ugly emotions out even if the beat is polite. My lyrics present why they are in that groove," says MC Kaur

Gully Boy, she says, has helped bring attention to the field, as well as opportunities for her. "But where were you before the movie?" she asks. The film, she says, has validated the independent hip-hop scene (which has traditionally been under the shadow of Bollywood music) but people are still unwilling to pay for independent music. "I just hope this doesn't become a trend that disappears after Bollywood picked it up… I guess it's up to us how we take it from here."

MANMEET KAUR (MC Kaur), a rapper from Punjab now based in Goa, is more sceptical of the effects of the film. "People were releasing their albums at the same time as the film but weren't really getting noticed," she says. "What troubled me though was the ads. People suddenly thought of me, even though I have been rapping for a long time."

Rolling Stone described Kaur as 'one of the most outspoken hip-hop artists in India,' in 2015. Her first album, Hip Hop Bahu, subverts the trope of the docile Indian daughter in-law. Blending rap lyrics and blues-like melodies, it places the bahu in transgressive positions that are at times comical. In Another Old Monk Day, the wife is caught drinking by her husband. In I Made Love to J. Dilla That Night, she has an orgasmic experience listening to hip-hop. Kaur's new album, Neophilia, has a quirkier sound palette that one doesn't immediately associate with rap. Impressions of funk and fleeting snatches often carry esoteric lyrics. Still, the incisive commentary on gender and capital come through in songs like Liberal Slavery.

When asked about her unusual sound (as compared to more mainstream rap), Kaur says, "I do give ugly emotions out even if the beat is polite. My lyrics present why they are in that groove. I don't want to be categorised."

Kaur left the Mumbai circuit to work in Goa. Performing in a tourist hub allowed her to meet artists from different parts of the world, which in turn led to a Europe tour. But this, too, was an independent and largely self-funded venture. Kaur wrote emails to venues around Europe, some of whom promised her a little money. Performing at arts spaces, cafes and festival abroad, she reached new audiences. "It's not a fan base," she clarifies, "but I got to socialise a little, let people know about my music."

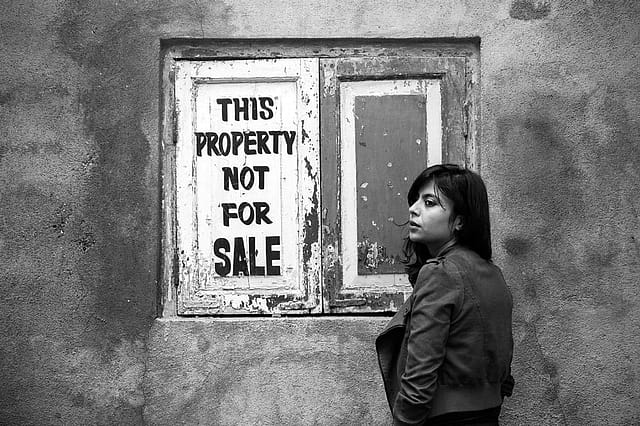

"Honestly, I'd rather not be called a female rapper. Just a rapper," says Siri

While Kaur chooses to work in a fiercely independent manner, she reveals that it is difficult. For instance, she shot a video in Brussels but doesn't have the funds to edit it and publish it on YouTube—one of the best ways to promote one's music these days. But she seems sure of where she has positioned herself. "I know what I don't want to do with my music," she says. "I have to ask, what's my participation when all the attention goes to singer-songwriters? So much of your own money can go into platforms of mass distribution, like Spotify, which eventually don't give back to the artist. I don't want to work with those. That's why people think I am unprofitable."

Kaur is also working with artists from other styles in the independent scene. Her latest collaboration is with electronic/ experimental composer, Pulpy Shilpy, best known for her trippy Tamil track, Kaadal Mannan. Together they are part of a collective called Orbs Cure Labs, which brings together the 'underground female producers and composers of South Asia.' Kaur says the collective is a gesture towards solidarity between independent women artists. "Solidarity can intimidate others. Sometimes we are kept away from each other because of our own insecurities, but also by men. The collective is about a togetherness we want to see at an artistic level."