Weaving a Legacy

"GANDHI ONCE SAID that the history of India may well be written with textiles as its leading motif," said Martand Singh (1947- 2017), or Mapu as he was affectionately known, in a fascinating interview with fashion stylist Prasad Bidapa. The hour-long interview, in many ways, sets the tone for the exhibition commemorating Mapu, arguably India's best-known textile revivalist and expert on traditional and contemporary textiles and fashion who also designed the landmark Vishwakarma Master Weavers exhibitions for the Festivals of India in the 1980s and 1990s.

It's also a fascinating thought. After all, India became the forerunner in dyeing and printing techniques as far back as the Indus Valley Civilisation, since blue dye could only be generated from indigo plants; and the knowledge of extracting blue colour from the green leaves of indigo plants was closely guarded within families and passed on to the next generation. When the British landed on the Indian mainland in 1608, the most sought after commodity was indigo. From the mid-17th century onwards, Indian textiles were sought after by Europeans to the extent that, between 1670 and 1760, the East India Company imported an average of 15 million yards of Indian cotton cloth annually, till, in an attempt to protect the interest of European woollen, linen and silk manufacturers, a series of acts first limited and then banned the trade and consumption of Indian cotton cloth. Cotton mills in Manchester were set up, using Indian expertise and knowledge, at the expense of the Indian textile industry. The great Bengal famine in 1943 was a result of colonial mismanagement and farmers being forced to grow more indigo since the British now profited handsomely from its sales.

In this light, it's astonishing that handloom fabrics have survived at all. A big part of the credit goes to Gandhi's insistence on making khadi a symbol of national pride, and the politicians and freedom fighters of that age who wore it dedicatedly. The Beatles, in their Indian kurtas, also helped the cause.

From the 1950s onwards, India's cultural tsarinas Pupul Jayakar and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay were at the vanguard of the revival. Chattopadhyay set up the Central Cottage Industries Emporium and the Crafts Council of India and Jayakar set up the 28 Weavers Service Centres in the 1950s where some of India's greatest artists of the time were employed. Mapu, a scion of the royal family of Kapurthala, worked with Jayakar in the Handlooms & Handicrafts Export Corporation of India in the 70s. He was the director of the Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmadabad when Jayakar asked him to put together the Master Weaver's exhibition for the Festival of India. Mapu travelled to the Weaver's Service Centres across the country where notable artists like Gautam Waghela, KG Subramanian and Manu Parekh had been quietly documenting Indian cloth to create a coherent record of textiles and weaves across the country.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

In 1981, the Vishwakarma Exhibition that went to Britain as part of the Festival of India brought together these efforts from almost every state capital. Mapu's chutzpah and eye for quality made Vishwakarma a rallying point to reintroduce amazing creations like the patola, kanjeevarams and gharcholas. The subsequent exhibitions travelled to the United States, Japan, China, Sweden, Italy, France and Russia, and for the first time systematically showcased India's glorious textile heritage.

But Mapu's real strength lay in building teams. He's still doing it posthumously.

About a month after Mapu passed away, art historian and author Shobita Punja, textile designer Rakesh Thakore, art historian Rahul Jain, author and design developer Rta Kapur Chishti, and the founder of the Devi Art Foundation Lekha Poddar decided to organise a commemorative display on Mapu and the Vishwakarma exhibitions. The Crafts Museum seemed the fitting venue since a substantial number of the Vishwakarma textiles were housed there.

This means that the exhibition, in its current state, contains 36 pieces—mostly the ones that were housed in Delhi. But even if they provide only a hint of what was shown at the Vishwakarma exhibitions, it's a grand and glorious clue. On the afternoon I went, attendees from Tokyo and California were being shown around by some of India's best known textile experts.

The show itself focuses on five of India's traditional textile techniques, including pigment-painting (for example kalamkari and pichvais), dye-painting (block printing), resist-dyeing (patola), printing (ikat) and weaving (Banarsis). It's divided into two galleries. The first gallery showcases textiles that were intended to project a strong classical/ traditional sensibility. Mapu took the textures, colours and patterns from museum-quality historical pieces and references and worked with weavers to create textiles that discarded decorative elements that were out of harmony. He trimmed decorative excess, eliminated strongly contextual images and symbols, and reformatted design layouts, to create a 'new but classical' genre of textiles that could fit comfortably into contemporary homes and public spaces.

He believed that textiles with ritual significance couldn't be taken out of context and if removed, the content imagery had to change. For example, a beautiful Padma Pichhavai created by Vithal Dasji from Nathdwara for the first Vishwakarma show in 1981 shows lotuses in various stages of bloom, surrounded by small birds, bees and butterflies. While the symbolism conveys the meaning of a traditional pichhavai, Mapu eliminated the gods and goddesses that make a pichhavai a temple hanging. "The lotuses symbolise the Godhead (Vishnu)," explains noted textile designer Rajiv Sethi, who was also visiting the exhibition with friends. "The bees are the devotees who know that if they go into the lotus in the night and it shuts, they will die, but still can't stay away." The Morkuti Pichhavai next to it derives its name from a small village near Vraj where Krishna is said to have danced like a peacock to court Radha. It shows 12 peacocks dancing for the attention of a flock of peahens in staggered rows. The traditional rasa mandala temple-hanging would have shown a dancing Krishna encircled by dancing gopis, and the peacock plume remains one of Krishna's best-loved symbols.

The design of an unforgettable Nagabandha Ikat Sari emerged from conversations with one of the master craftsmen from Sonepur and was created by Weavers Service Centre, Bhubaneshwar, for the 1981 show. This textile depicts, in weft ikat, a series of bandhas (cryptic poems) composed by the Oriya poet Upendra Bhanja. These textual and diagrammatic poems, if properly deciphered, apparently reveal secret messages between lovers. The diagrammatic ones such as those represented by coiled serpents, lotuses or fish ponds, can only be decoded if their beej (key) is identified.

The bandha text and patterns of this sari, which typically took over a year a weave, make it a challenge to tie. But this isn't all. Fish and rudraksh motifs are woven on the side borders by means of a supplementary warp.

Mapu mentions in the filmed interview with Prasad Bidapa that when these saris were on sale in India, Indira Gandhi found herself fighting over one with another lady who said, "This is mine." Later realising whom she was speaking to, the lady offered Mrs Gandhi the piece, but she politely refused.

"He brought in a new vocabulary, a new language," says Rakesh Thakore, one of the show's curators. Every village where Mapu went in Andhra Pradesh when he was preparing for the first Vishwakarma, he was told that a certain student from National Institute of Design (NID) had been there before him. He went back to Ahmedabad and asked the director of NID about this student. Since Thakore—the student in question—had finished his studies, he started working with Mapu. "The aim of the Vishwakarma exhibitions was to create a revival of textile techniques and a directory of techniques like patola, ikat, etcetera, as well as a contemporary language of textiles. Catalogues were produced so that people had direct access to the people at the centres. Of course, the force behind the Weavers Centres was Mrs Jayakar, and thanks to her, a lot of the work for the festival was done at the Centres."

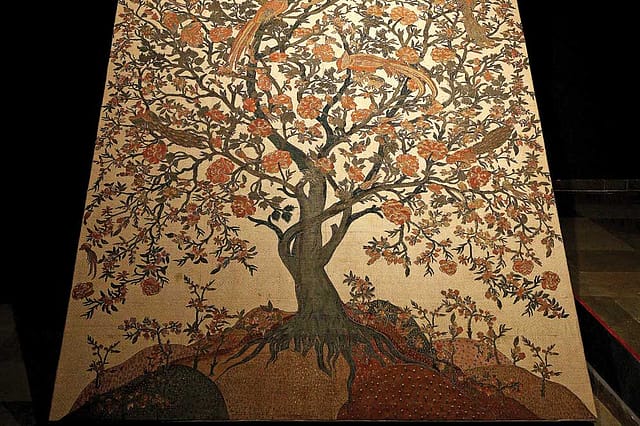

Thakore's favourite piece in the show is a Kodali Karuppur sari created by B Kanniah and P Sivaraman in Hyderabad and Chennai and shown in the 1981 and 1986 exhibitions. "This is a great example of the dialogue between the brocade weaver, the hand painter and the hand block printer," he says. His WhatsApp profile has him standing in front of an extraordinary Kalamkari Tree of Life created by M Kailasam, R Sundarrajan and JK Reddiya in Hyderabad for the 1981 show, which is also Rta Kapur Chisti's favourite piece. In its use of directly-applied indigo, the textile represents a milestone in contemporary dyeing, but it still doesn't manage to achieve a clear white ground fabric after the dye-painting processes, which means that its natural dyes are not nearly as brilliant as in the historical examples. It's breathtaking all the same.

Lekha Poddar's favourite piece lies in the second gallery. This gallery is devoted to visionary textiles that were designed to create new conversations and a future for textile arts. The 30 by 15 foot piece was resist-printed panel and dyed in Chennai for the 1991 exhibition. It's covered with birds and animals in motion. No two the same. "How did the weaver move the shuttle over such a large area? It's a single piece without joints," she exclaims of the piece. New blocks must certainly have had to be created for this piece. The fauna is extraordinary and the cloth has a soft, rich luster.

The second gallery also houses textiles that are printed by master block- makers of Pethapur, Gujarat. There are more than 100 designs on one fabric. There are similar pieces from Bagru and Sanganer—treasure troves that could help any designer studying the design history of India. Even the text on the walls is taken from books that are no longer in print. And the thought that constantly goes through my mind is that these are just 36 one-of-a-kind heirloom pieces. The rest, as Chishti mentions, were not in good condition or not fully representative of the five directions of the show.

But Vishwakarma is in the past. This show helps us teach the young about textile design possibilities in India, assess what has survived the 20 odd years since Vishwakarma ended, and remind fashion and textile houses in India and abroad of the richness of our textiles and designs.

But what is the ground reality now? The Weaver Service Centres, without great artists at the helm and deep governmental pockets to lend support, are no longer equipped to produce this quality of material.

'You need a patron," Poddar muses. "Earlier it used to be royalty and nobility. Post independence, the state stepped in. Mrs Jayakar impressed Mrs Gandhi with the need for state intervention. Post economic liberalisation, people were interested in creating their own status, and heritage was forgotten. What was created was pop culture. Now there's not much money and the weavers are dying. We hope that this will inspire people in India. We are the last country left with this tradition of textile making. Where else can you ask a weaver to spin and weave five metres of cloth? But the weavers, even the few remaining ones from the last Festival of India, need design inputs. The same designs are being bandied around. They have the skills but not the design. They also need people to engage with. I don't know if we can even produce the same things we produced in the 1980s. The soil, water and climate have changed since then. Effort needs to be put in to take this forward. Even if private people adopt two or three weavers and even if the master weaver creates two pieces, let it be for a different market and not the mass one. I pray and hope the next generation looks at it as an asset. There is still time to nurture excellence."

(A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions runs at the Crafts Museum, Delhi, till March 31)