She and the City

The alleged encounter killing of the four accused in the rape and murder of a veterinarian in Hyderabad may have made heroes of the police. But at the same time, officers in plainclothes are making the city safer for women

/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SheandtheCity1.jpg)

Hyderabad Commissioner of Police Anjani Kumar (centre) with SHE Teams and officers associated with them

A FORTNIGHT AFTER THE NATION erupted with rage at the rape and murder of a 27-year-old veterinarian on the outskirts of Hyderabad, VC Sajjanar, Commissioner of Police, Cyberabad, dialled into a conference call with DCP (Women and Child Safety Wing) C Anasuya and a handful of police officers. Eight days after the incident, in a controversial turn of events that had vigilante justice written all over it, Cyberabad police had gunned down, supposedly in self-defence, the four accused in the case. The encounter may have brought a sense of closure to the family of the victim referred to as Disha, but for Sajjanar, the face of the operation, and his team, the chapter was far from resolved. Not only because they were facing a probe into an alleged extrajudicial execution but because in the endless pursuit to keep the modern metropolis free of marauders, there are many surprises.

The 40-minute conference call was about pushing past society’s baseline expectations from police and finding ways to make women feel safer—not by dangling punishment as a deterrent against crime but by using an array of less formal techniques to keep urban spaces orderly and safe. As many as 228 dark spots had been identified in Cyberabad and the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation was being asked to light them up, ventured an inspector listening in to the meeting even as she counselled a distraught newlywed and her parents who had allegedly been beaten up by the groom’s family. Patrol teams would be held accountable for every minute they spent on the streets, another officer noted. Abandoned buildings and vehicles parked in no-parking zones would be monitored closely. Staff at filling stations would be sensitised to report suspicious activities. Finally, the ‘Zero FIR’ policy—under which a police station cannot refuse to register complaints that fall under the jurisdiction of another—would be implemented without exception. To my surprise, much of the conversation was about keeping peace rather than the far more dashing proposition of fighting crime.

Lost in the noise around the alleged encounter killings that have made overnight heroes out of the Cyberabad police is a thoughtful programme to boost the safety of women in public spaces in the city. The SHE (Security for Her Ensured) Teams began five years ago as a low-profile endeavour of the Telangana Police to encourage women to report crimes against them without the fear of being judged. But there was a hitch. Few women knew what constituted a crime or how to report one. In a country where women put up with being stalked, threatened and groped on buses and trains, it is not easy to break the silences surrounding violence and aggression. It is harder still to convince them not to cede public spaces to men in pliant self-preservation. Working in groups of three or four, the SHE Teams began infiltrating areas where women were most susceptible to harassment—bus stops, train stations, outside colleges and schools, crowded markets, festive gatherings. They would don civilian clothing, blend into the crowd at these ‘hotspots’ and watch out for perpetrators who whistled at, touched, propositioned, followed or otherwise harassed a woman. The act would be recorded discreetly on camera and they would be apprehended and taken to a SHE Teams centre—it also acts as a friendly interface where women who don’t feel like approaching a police station can walk in and report crimes—where their parents, spouses or children would be summoned and notified of their reprehensible activities. First-time offenders would be let off with a warning and put through a counselling programme, or booked suo motu under Section 70 (c) of the Hyderabad City Police Act and Section 190 of the Indian Penal Code (causing public nuisance). More serious offences would be booked under sections in the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, including IPC 354A (sexual harassment).

In India, even as our collective conscience is roiled by horrific crimes against women, convictions under the updated anti-rape laws continue to be few and far between

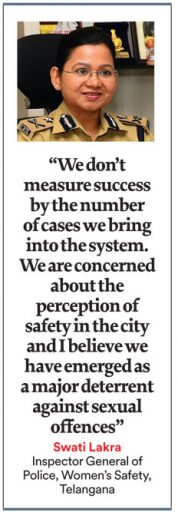

Between 2014 and 2019, the SHE Teams in Hyderabad booked 5,608 petty cases, warned and let off 10,161, registered 2,587 FIRs and counselled and monitored 12,188. According to an internal survey by the Telangana Police, 76 per cent of people in Hyderabad are aware of SHE Teams and most of them (85 per cent) reported feeling safe and secure. “We don’t measure success by the number of cases we bring into the system. We are concerned about the perception of safety in the city and I believe we have emerged as a major deterrent against sexual offences,” says Swati Lakra, Inspector General of Police, Women’s Safety, Telangana. “Until the Disha case, Hyderabad had the reputation of being a safe city for women,” says Lakra, a founding member of the SHE Teams. Five years ago, when policing was more about incarcerating for the tenth offence, a rape or a murder, the SHE Teams started working with the community to address delinquency among minors and the youth—unprecedented for the police, who are conditioned to see themselves as the thin blue line guarding civilised society from the forces of evil. “In the beginning, over 70 per cent of the offenders were minors. That number is down to 20 per cent now. That we have been able to positively influence a generation about their attitude towards women is an achievement that is its own reward,” Lakra says.

On a Sunday afternoon, the SHE Teams office near the Public Gardens in the heart of the city is quiet but for a group huddled over a desk. Bhavya Bandla, 30, is the youngest member of the team led by Inspector Ramlal Amgoth. “On weekends, we patrol public parks, malls and theatres,” says the constable, smoothing down her crisp salwar-suit. “On other days, the focus is on spots at SR Nagar, due to the number of women’s hostels there, Ameerpet Metro station, the University College for Women in Koti and other places of study or work where women emerge in large numbers at certain times of the day. Offenders wait at these spots for an opportunity,” says Bandla. “Our job is to give them none.” It is 4 pm when a battered SUV drops us off at the vegetable market adjoining Mehdipatnam bus stop. Bandla takes up a corner perch, her earphones plugged in and her game face on. I Radha, 42, lumbers towards a sallow middle-aged woman and makes small talk. P Rakesh, a 38-year-old constable, appears engrossed in a video on his phone. Amgoth makes a convincing commuter, anxiously scanning bus numbers and pacing up and down the platforms. Fifteen minutes later, the team has doubled down on a suspect in a black t-shirt and discreetly positioned themselves around him. Over the next few minutes, they shoot videos from different vantages of the man sidling up to a young woman in a <burkha>. The moment she is left sitting alone on a platform bench, he swoops into the seat next to her and tries to strike up a conversation even as she moves away. The SHE Team has seen enough. They close in on the perpetrator, who at first feigns outrage but begs to be pardoned as soon as they produce the evidence and the young woman confirms that he foisted himself on her. Onlookers who by now have put two and two together cast knowing glances at the team as they make a quiet exit, taking the offender with them. Back at the SHE Teams office, Rakesh clicks a picture of him and fills in a form. The 36-year-old, an engineer from the Old City who claims to run a pesticides business, admits to his “mistake”, strategically lapsing into English. Rakesh is not impressed. He rings his wife and his brother and tells them the man is up to no good. “Come and take him. We are located at Metro pillar 1239, opposite the Traffic Control Room,” he tells them. The team is yet to decide if they will charge him formally, or simply put him on their watchlist. “Following up with offenders and their families every fortnight for the first six months, and less frequently thereafter, seems to work in most cases. The number of repeat offences is negligible,” Amgoth says.

What made the team suspect the man even before he made a move? “His body language,” Amgoth says. He had seemed in no hurry to board a bus and stood on a platform casting sidelong glances at women and dangling his motorbike keys. “Had he stopped short of making unsolicited conversation, we would have let him go with a warning. Much as we would like to confront any man who makes women uncomfortable in public, we have neither the resources nor the sanction of the law to do so. We act only when we are able to gather conclusive evidence—and this is why the conviction rate in suo motu cases registered by the SHE Teams is close to 100 per cent,” says the inspector.

THE NUMBER OF SHE TEAMS watching the city is a closely guarded secret, but their impact has been significant enough for other states like Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh to adopt the model. “The SHE Teams are practically a zero-budget initiative. We pick up and train a small number of police personnel who serve on SHE Teams for a year or two and then return to assume regular policing duties,” says Lakra, stressing the importance of picking the right people. While empty-holster assignments normally tend to be seen as punishments, a stint with a SHE Team is now a matter of prestige, especially for men in the police, multiple sources said. “The SHE Teams is a model initiative in many ways, but most importantly for introducing the element of approachability that was missing from policing,” says Shikha Goel, Additional Commissioner of Crimes, Hyderabad. A WhatsApp number, a smartphone app and ‘Bharosa’ support centres employing medical and mental health professionals to counsel women and child victims have further bolstered the image of SHE Teams as a friendly redress forum for women. “More women are walking through our doors now than ever before. And if this results in an uptick in the number of crimes reported, so be it. It represents a paradigm shift in the attitude of women towards their aggressors,” says Lakra.

According to the United Nations, over a third of women are affected by violence at some point in their lives. A World Mental Health Survey conducted by the World Health Organisation among 68,894 people across 24 countries has found that of 29 traumas the respondents had experienced in their lives, the risk of post-traumatic stress and its persistence were highest in the case of rape (13.1 per cent) and other sexual assault (15.1 per cent). The unexpected death of a loved one came in third at 11.6 per cent, ahead of being stalked (9.8 per cent). In India, even as our collective conscience is roiled by horrific crimes against women, convictions under the updated anti-rape laws continue to be few and far between. Consider the fact that while 32,559 rapes were reported in India in the year 2017, courts pronounced judgment on only about 18,300 cases related to rape that year, leaving over 1,27,800 cases pending. “We have been working on improving our conviction rate but there is little we can do when victims turn hostile,” says an officer at the police headquarters in Cyberabad, one of the three commissionerates sharing jurisdiction over Hyderabad city and its expanding suburbs. “The encounter in the Disha case will not only serve to restore the people’s faith in the police’s efforts to secure justice, it will also drive the fear of God into rapists. They now know that should they be caught—and they will be because we have 10 lakh CCTV cameras watching the city—they can no longer hide in the nooks and crannies of the criminal justice system,” he says. The TV in the room is tuned to a Telugu news channel running the story of the serial murders of minor girls in Hajipur, Nalgonda district, where residents are now demanding the suspect, M Srinivas Reddy, be “encountered”. The trial began in October before a local fast-track court in Nalgonda and a verdict is expected soon.

Last year, 17 men were charged in Chennai with repeatedly raping a 12-year-old girl over a seven-month period, sedating her and taking her to vacant apartments in a residential society in Ayanavaram to assault her. The POCSO court in Chennai has reserved judgment in the case and the prosecution is hopeful of an exemplary verdict. In another eagerly awaited verdict, all the 20 accused in the case of sexual and physical assault of several minor girls in a shelter home in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur are expected to be incarcerated.

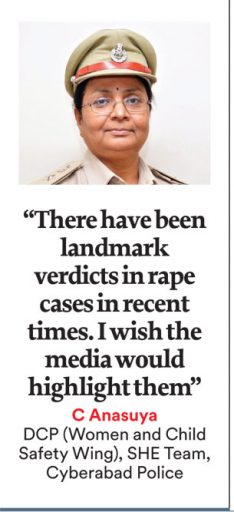

“There have been landmark verdicts in rape cases in recent times. I wish the media would highlight them,” says DCP C Anasuya. Her team recently secured life sentences in two POCSO Act cases—for all the four accused of the rape of a minor girl in 2013 in Balanagar, and for Eppili Krishna, who had kidnapped, raped and impregnated a Class 7 student in a case registered in Kukatpally in 2016. The law does take its time, however, despite fast-track court hearings, and defence proceedings often resort to character assassination of the survivor, echoing the insidious subculture that allows and apologises for rape.

Coming at a time when we await justice for the young woman who accused Uttar Pradesh lawmaker Kuldeep Singh Sengar of raping her in 2017 and mourn for the 23-year-old victim set ablaze by four men, including her alleged rapist, on her way to court to attend a hearing in the case in Unnao, the rape and murder of Disha, a young doctor from Hyderabad with a bright future ahead of her, has smacked us in the face with the uncanny truth that it could just as well have happened to our sisters and daughters. In the aftermath of the tragedy, it is not the death of her alleged aggressors that inspires confidence, but the fact that the police and civil society are reimagining safety as an urban reclamation project. The SHE Teams, which work on the guiding principle that a rapist is a power-drunk man who has never been apprehended before and therefore feels emboldened to act upon his lust, have contributed to taking an active policing approach to women’s security. In Hyderabad, as in other metros, safety has until now been largely addressed in terms of surveillance and technology, making the city more investigatable but not necessarily more women-friendly.

Cyberabad, where a burgeoning IT industry has brought a large number of urban, educated women, is a conspicuous ‘hotspot’ attracting not only men from the villages who are on the lookout for ‘easy’ women, but also educated youth from small towns who are resentful of their success. Add to this cultural malaise the unpredictable disconnects in urban infrastructure, and the odds against the women who work in the IT corridor stack up pretty high. Cyberabad presents unique challenges for various reasons, says Anant Maringanti, director of the Hyderabad Urban Lab, a multi-disciplinary urban research centre. “It is the woman who cannot afford to hail a cab, who must board an empty bus in the night, who has no choice but to seek the help of a bystander to fix her scooter, who becomes susceptible. She falls through the cracks of an urban infrastructure that favours private vehicles over pedestians and public transport,” he says.

In 2013, two men in a Volvo car were charged with the abduction, rape and criminal intimidation of a 23-year-old software engineer who had been waiting for transport at a junction near Inorbit Mall in Madhapur late in the evening. Exploiting the situation, the duo had offered her a ride for Rs 40 but what ensued was a six-hour-long ordeal of rape and abuse at the end of which they dropped her off at her hostel, warning her not to report the incident. The victim, whom the police call ‘Abhaya’, almost didn’t. Today, she would likely approach a SHE Team. What hasn’t changed, however, is the fact that she would still have to wait for an affordable ride and take unnecessary risks in her day-to-day life just to get to work and back.

Also Read

Beyond the scapegoat ~ by Nandini Nair

Not in my name ~ by Mehr Tarar

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita

5 Proven Tips To Manage Pre-Diabetes Naturally Dr. Kriti Soni

Keeping Bangladesh at Bay Siddharth Singh