A Turmoil Called Trump

America is in the grip of a historic drama of disruptions

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

|

11 Oct, 2019

|

11 Oct, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/TurmoilTrump.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

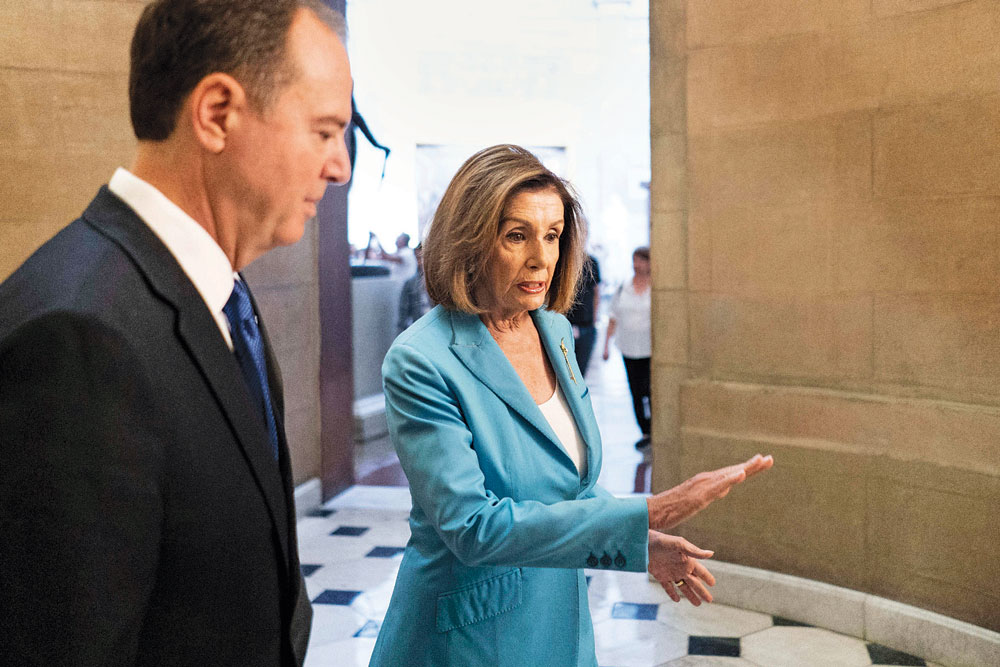

NOBODY COULD ACCUSE Nancy Pelosi of taking the decision to impeach the president lightly. Ever since she resumed as Speaker of the House of Representatives in January, the veteran Democrat had been resisting demands from some in her party to put Donald Trump on trial for his job in the Senate. Even after the president was implicitly accused of obstructing justice—the crime that did for Richard Nixon and triggered the failed impeachment of Bill Clinton—by Special Counsel Robert Mueller in July, Pelosi held firm.

Though the Democratic-controlled House might win a vote to issue articles of impeachment against Trump, she argued, the Republican-controlled Senate would not vote to convict him. And a failed impeachment could potentially be a vote-winner for Trump, just as, arguably, it was for Clinton’s party in the late 1990s. Moreover, Pelosi would add, the president was just ‘not worth’ taking any sort of political risk for. An inveterate rule-breaker, whose behaviour has grown predictably more egregious during his tenure in the White House, she argued, no one should waste time being surprised or outraged by him. Trump and his abuses were a known quantity. He is what he is. Better by far, then, for Democrats to pour their energies into removing Trump by the more reliable means of the ballot box.

Then why did Pelosi so dramatically change tack two weeks ago? After all, most of her aforementioned reasons for resisting the pressure from the pro-impeachment left of her party probably still hold good. A president who once boasted he could stand in the middle of Manhattan and shoot someone without losing a vote, such is his hold on his supporters, is still unlikely to be abandoned and disgraced by Republican Senators. A failed impeachment still risks handing him re-election—and perhaps control of the House back to the Republicans—at next year’s general election. And yet, last month Pelosi launched an impeachment investigation into Trump that is now almost certain to lead to the House passing the ‘articles of impeachment’ that would put him on trial in the Senate. There are two reasons for this change.

The latest allegations against Trump are so grave that Pelosi felt she had little choice but to press for his removal. Not to have done so would have called into question what purpose Congress’ constitutional powers of impeachment serve. And, for much the same reason, Pelosi would have faced huge opposition from within the ranks of her own party if she had continued to desist.

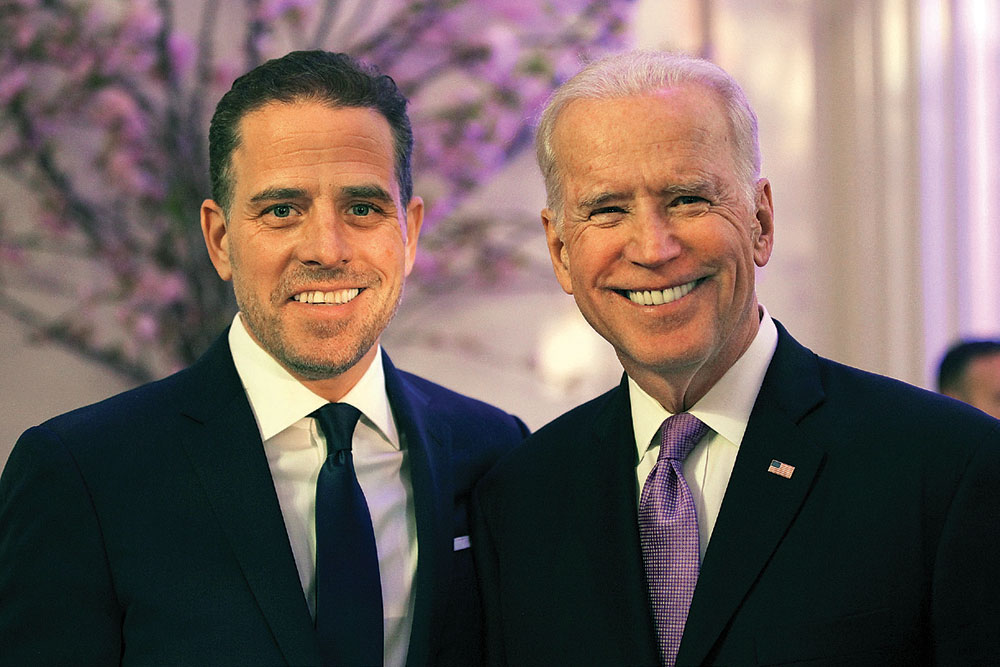

The president was accused by a CIA whistleblower last month of trying to pressure Ukraine’s President Volodomyr Zelensky to launch an investigation into his most feared Democratic rival, Joe Biden. Biden, Barack Obama’s former vice president, is running for the Democratic ticket to challenge Trump in next year’s general election. There is otherwise no credible reason why Trump would be so anxious to have the Ukrainians investigate him. Trump and some of his acolytes have suggested that Biden’s lobbyist son, Hunter Biden, was engaged in corrupt business in Ukraine and that Biden intervened to protect him from exposure. But there is no evidence for this claim. Hunter Biden appears to have cashed in on his father’s name in a way that was unsavoury, probably inappropriate, and run-of-the-mill in Washington DC. But there is no reason to suspect him of corruption in Ukraine or Biden of protecting him there. At the same time, Trump has a long history of inventing and spreading malicious conspiracy theories about his political rivals (that Barack Obama was born in Africa, for example, Hillary Clinton guilty of gross corruption). The pressure he applied on Zelensky therefore looks like a straightforward effort by Trump to direct American foreign policy to persecuting one of his domestic rivals for his own political ends.

It already seems all but certain that Trump will become the third US president impeached by Congress. Once the Judiciary Committee has drafted its charge-sheet, House Democrats are expected to vote more or less unanimously to send it up to the Senate. What happens after that may well define Trump’s presidency; or, seal his hopes of winning re-election

‘If these allegations are true,’ wrote a group of moderate Democratic members of Congress in a joint op-ed in The Washington Post, ‘We believe these actions represent an impeachable offense.’ That verdict—from a group that had hitherto been as reluctant to push the impeachment button as Pelosi—was instrumental in the Democratic Speaker’s dramatic about-face. It suggested she faced a possible mutiny within the Democratic ranks if she did not launch the impeachment inquiry she had previously resisted. But what genie has her change of plan let loose?

First, consider the practicalities. Though Pelosi has formally committed only to investigating Trump with a view to a possible impeachment charge, there is already little doubt that a charge will ensue—thus making him only the third president to suffer that disgrace. It also seems likely that the expected articles of impeachment, which will be drafted by the House Judiciary Committee, will focus quite narrowly on the Ukraine scandal. While some Democrats would prefer to see a longer list of charges—to include Trump’s alleged abuse of office, efforts to profit from his office, and so forth—Pelosi believes that might seem to corroborate Trump’s claim to be a victim of a left-wing witch-hunt. There are also signs that the Ukraine plot is more likely to cause public disquiet—especially among moderate Republicans and conservative-minded independents, Trump’s flakiest supporters. Though Americans are starkly divided on the impeachment question on partisan lines, opinion polls nonetheless suggest a modest uptick in support for impeaching Trump since Pelosi launched her investigation.

Bizarrely, Trump has done nothing to reassure his doubters. Nixon and Clinton both denied the allegations levelled against them; an oddity of Trump’s defence is that it appears to involve admitting, tacitly or otherwise, most of what he stands accused of. In response to being accused of leaning on Zelensky to investigate the Bidens, for example, Trump essentially said: “Damn, right I did!” He maintains that the Bidens are guilty of serious corruption in Ukraine, and that it is well within the ambit of his presidential powers to use foreign policy to go after a domestic rival in such circumstances. The White House therefore released—uncompelled—a record of a phone conversation between the two presidents on July 25th that provided the evidence of Trump’s scheme in black-and-white. “There is a lot of talk about Biden’s son, that Biden stopped the prosecution, and a lot of people want to find out about that,” Trump is recorded as saying to Zelensky. (Again, for the avoidance of any possible doubt, there is no such talk about Hunter Biden, there was no prosecution, and the only people who say otherwise are the president and his lackeys).

Trump and some of his acolytes have suggested that Hunter Biden was engaged in corrupt business in Ukraine and that Joe Biden intervened to protect him. But there is no evidence for this claim. Hunter appears to have cashed in on his father’s name in a way that was unsavoury and run-of-the-mill in Washington DC. But there is no reason to suspect him of corruption

The transcript even appeared to give credence to the most serious of the allegations against Trump: that he was not merely leaning on Zelensky to intervene in American electoral politics, but also offering the Ukrainian a quid pro quo. After Zelensky expressed an interest in buying American military kit, Trump is shown to have replied: “I would like you to do us a favour though…” before proceeding to outline his political demands. The president then assured Zelensky that his attorney-general, Bill Barr, would follow up on the details.

IT IS SO HARD to think how the administration could have considered this record exculpatory that some suspect Trump of setting a cunning trap. He must want to be impeached, they argue. He must have concluded, with Pelosi, that such a course would be bound to fail, probably to his and his party’s advantage. The extent to which Trump has continued to worsen his already dire predicament is indeed astonishing. Asked by reporters last week what exactly he had wanted of Zelensky, he replied, “a major investigation of the Bidens”. Then he added that China, for some weird and unexamined reason, should also investigate the former vice president: “Likewise, China should start an investigation into the Bidens because what happened in China is just about as bad as what happened with Ukraine.” (A Chinese spokesman, throwing shade in Trump’s direction rather magnificently, responded by suggesting that China saw no reason to involve itself in America’s domestic politics.)

Such oddities aside, it only takes half a minute perusing the president’s Twitter account to conclude that there is nothing terribly cunning or trap-like about his behaviour. The crazy invective he is firing off at his ‘treasonous’ Democratic accusers, often in the early hours, does not point to a man in control of his emotions, much less to tactical nous. It points, as so much of Trump’s behaviour does, to an intemperate narcissist with a sketchy idea of the limits of presidential power and no interest in educating himself. Making matters worse for Trump’s fragile state of mind, he is said to be keenly aware of the stain Bill Clinton’s impeachment attached to his presidency, albeit that it did not curtail it. Far from welcoming his looming impeachment, Trump is plainly horrified by the prospect.

Even so, the president’s weirdly self-incriminating behaviour, wittingly or otherwise, could conceivably work to his advantage in a couple of ways. It can be viewed as an effort to shift the boundaries of acceptable presidential behaviour—by admitting everything, but refusing to accept there was anything wrong in it. That may be the only defensive course available to him, given that evidence of his Ukraine scheme would have emerged whether he liked it or not. His administration is as leaky as can be. Moreover, the instant House Democrats launched an impeachment inquiry into him, their subpoenas grew legal teeth. That is already apparent in the high-profile witnesses the Democrats have already successfully summoned to testify on their role in the Ukraine affair.

The first of them, Karl Volker, Trump’s erstwhile envoy to Ukraine, provided evidence that the pressure campaign on Zelensky went even deeper than had been suspected. He supplied his Democratic interrogators with a series of text-messages—which they promptly made public—detailing the efforts that he and other American diplomats went to, to persuade Zelensky to launch the investigation into Biden that Trump had demanded. The texts also provide clearer evidence that Ukraine—as had been made clear to Zelensky—stood to gain or lose standing with America according to its willingness to play ball. For example, they make clear that there was an understanding in both countries that the Oval Office meeting with Trump that Zelensky had requested would be contingent on his willingness to announce the requisite investigation. And there are likely to be more such revelations; a second whistleblower, with even more direct knowledge of Trump’s Ukraine scheme than the first, is reported to be assisting the Democrats with their investigations.

Though it is early days for Pelosi’s impeachment inquiry, it therefore already seems all but certain that Trump will become the third US president impeached by Congress. Once the Judiciary Committee has drafted its charge-sheet, House Democrats are expected to vote more or less unanimously to send it up to the Senate.

What happens after that may well define Trump’s presidency; or, for that matter, seal his hopes of winning re-election.

The latest allegations against Trump are so grave that Nancy Pelosi felt she had little choice but to press for his removal. Not to have done so would have called into question what purpose Congress’ constitutional powers of impeachment serve. Pelosi would have faced huge opposition from within the ranks of her own party if she had continued to desist

Pelosi’s original calculation, that there is no serious prospect of the Senate mustering the requisite two-thirds majority to convict Trump, probably still holds good. For, this would require 20 Republican Senators to turn against a president who boasts record-high approval ratings among Republican voters. And there is little in the latest opinion polls to suggest the prospect of Trump’s impeachment is making many Republicans question their loyalty to him. Yet, a few of them are looking shaky. Around 12 per cent of self-identified Republicans say they are pro-impeachment. Given that Trump won power in 2016 by the narrowest of margins and that, given his considerable unpopularity, he is unlikely to do much better next year, those Republican naysayers could turn out to be highly significant.

Whether they maintain their opposition to the president, and even grown in number, will probably depend on a few Republican Senators also condemning his behaviour. And again, that looks slightly likelier than it did. Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential candidate in 2012, who is now representing Utah in the Senate, has already suggested he might vote to convict his party leader and president. ‘By all appearances, the president’s brazen and unprecedented appeal to China and to Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden is wrong and appalling,’ he tweeted.

Romney is, to be sure, unusually well-placed among Republicans to dare to offer such criticism. Having been elected to the Senate only last year, he is in no imminent danger of a Trump-engineered primary challenge. And Trump is not all that popular among the high-minded Mormons who dominate politics in Utah. Yet, if Romney holds firm, it is not impossible to imagine one or two other Republican Senators joining him—especially those facing tough re-election fights next year in states where the president is even more unpopular. Susan Collins and Cory Gardner of, respectively, Maine and Colorado—two swing states where Trump’s ratings are under water—could fit that description. Again, that level of Republican dissidence would not lead to Trump’s removal. But it would make it harder for him to rally doubtful Republicans by dismissing his impeachment as a partisan stunt.

Such are the big new uncertainties that Trump’s latest scandal has suddenly injected into American politics. It hardly seems fair to America, and us all, after so many bouts of unseemly and often gratuitous Trump-related scandals and uncertainty, to have this thrust upon us. Millions of Americans—Republican and Democratic alike—have had enough of the turmoil Trump has brought. The world, with more to worry about than the latest Trump-orientate drama, has had enough of it. All the same, a presidential impeachment is no small affair and it would be a mistake to underestimate the potential America is now facing for a truly historic political drama and disruption. Of all Trump’s innumerable scandals, this looks like being the big one.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

India holds the upper hand as end of hostilities with Pakistan announced Open

Ajay Kumar Garg Engineering College (AKGEC), Ghaziabad Open Avenues

Sanskriti University Open Avenues