Dam Worries

Water is a resource Gujarat would have been flooded with had the Narmada project gone by plan. Instead, the state remains parched and farmers watch helplessly as reserves flow out to sea. It’s a story of alarming apathy

Hartosh Singh Bal

Hartosh Singh Bal

Hartosh Singh Bal

|

02 Jul, 2009

Hartosh Singh Bal

|

02 Jul, 2009

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IGHO0156ST.jpg)

Gujarat would have more water than it needs had the Narmada project gone by plan. Instead, the state is parched

For the past few years, water from the Narmada River has been flowing past Vikram Kanobhai’s custard apple and guava orchards in the village of Chaloda in Ahmedabad district, but he continues to rely on his tube wells for irrigation. He is not the only one. For the vast majority of Gujarat’s farmers, water from the Narmada is worse than a mirage—they can actually see it flowing by, without legally being able to make use of it. In the year of its scheduled completion, work is still to begin on almost the entire network that’s supposed carry water from the main canal to the fields of farmers.

To be exact, 75 per cent of the entire canal network is still to be built. As a result, as much as 93 per cent of Gujarat’s share of the river water stored in the Sardar Sarovar Dam could not be utilised last year. It was allowed to flow out to the sea. Much has been made of Gujarat’s agricultural success over the past few years. But this performance owes everything to a few good monsoons, because regular breaches and infrequent maintenance have meant that the area irrigated by water from the Narmada canal network in Gujarat has actually declined, year by year from 2004-05 onwards.

AQUA AMISS

To understand the extent of this failure, imagine a state that discharges 93 per cent of all electricity it generates into thin air because the subsidiary transmission lines have not been constructed to provide power to residences and factories. Given that the first 25 per cent of the canal network has been over 15 years in the making, it is amply clear that the project will drag on for at least another decade. This makes a mockery of the cost-benefit ratio that was cited to justify the dam in the first place. It is almost as if the state believes that for the vast majority of people, just to see the water flowing in the main canal is achievement enough. The failure to make this water usable is even more galling because the entire rationale for the Narmada project has been its capacity to provide irrigation facilities, power being only a subsidiary benefit of this enterprise.

Canals are crucial. The vast majority of the Rs 40,000 crore—for comparison, the entire National Highway budget for 2008 was Rs 11,450 crore—to be spent by the state on the project is earmarked for these canals. So far, the state has spent Rs 11,753 crore on the dam, the main canal, the powerhouse, rehabilitation of those displaced, and on the environment. Another Rs 11,756 crore has been spent on building one-fourth of the network, while it is claimed the remaining three-fourths will cost another Rs 13,700 crore. This is clearly an underestimate, and the project is badly strapped for cash.

So much so that Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd (SSNNL), the corporation overseeing the entire project in the state, has been forced to take the extreme step of issuing its bondholders a notice, asking for the surrender of its 20-year deep discount bonds—against the payment of Rs 50,000, instead of Rs 1.11 lakh committed. The bonds, priced at Rs 3,600 each, were issued in 1993 with a promise to pay Rs 1.11 lakh on maturity in 2014. A promise unkept.

As it turns out, SSNNL has also cut down on staff. The media has reported, with no denial issued, that staff strength stood at 11,000 in 1993 when work on the main canal was underway. The number was reduced to 8,000 in 2000, a figure further slashed to 3,000 in 2003-04. Since then, there has been no fresh recruitment to augment staff strength. Of the total staff strength of a little over 3,000 personnel, there are only 1,900 engineers left.

The distress cannot be disguised. The state government is now seeking the Centre’s help, but in the meantime, it continues to speak in different voices to keep its failure from becoming apparent; after all, survey after survey has rated the state highly on ‘good governance’, an image presumably worth protecting. But SSNNL is a publicly listed company, and thus subject to performance disclosure norms entailed therein. As part of SSNNL’s listing agreement with the Bombay Stock Exchange, it must put out a quarterly status report; in 2008, it stated that the project would be completed by 2009-10. Asked about this claim, the current SSNNL Chairman NV Patel tells Open, “Financially, no government can expect the project to be completed in the next year or two. It will take at least three to four years more. There is no point expecting miracles. One has to be balanced.”

Pressed further on the fact that this delay was calling into question the entire rationale for the dam, Patel loses his temper. “The Narmada Control Authority [the central body coordinating the project in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Maharashtra] is to blame,” he fumes, “Instead of facilitating [the project], they are delaying [it].” Given the fact that canal construction is entirely Gujarat’s responsibility, an enterprise in which no external agency can interfere, this answer defies all logic. But Patel is clear about where the blame lies, and calls an abrupt halt to the interview at this stage.

Yoginder K Alagh, director, Institute for Rural Management, Ahmedabad (Irma), and former minister for power at the Centre, has been one of the key proponents of the dam, and was involved in the conception and design of the project from the very beginning.

He likens the failure to utilise water from the reservoir to putting lots of money into a bank and not putting the balance to any use. “The more the delays, the fewer the benefits,” he says, “and the returns from the dam become very low. This is a real economic loss because there is a huge amount of investment locked up.”

MAKING DO

Farmers who don’t have access to groundwater, meanwhile, have had no choice but to pump water out of the canals flowing past their parched fields. Diesel pumps with pipes stretching for thousands of metres into neighbouring fields are a common sight along the canal network.

Digvijay Singh Jhala has 50 bighas of land close monsoonto the Vallabhipur Sub-Branch Canal in the village of Motatradia in Surendranagar district of Gujarat. He has two 6 horsepower pumps working to irrigate his brinjal crop. He has been drawing water from the canal for the past three years, but has problems galore. “We don’t know when the water comes and goes,” he says, “we live in fear.” There is no system to this supply of water, and that makes it impossible to plan anything. One year, he was charged Rs 350 for each pump. Other years, no one came around to check.

He also complains about the state of the canal. It is truly in bad shape. Even before completion, the network is already falling apart. Along stretches of the Vallabhipur canal, we find ourselves driving past a horror story—reeds growing head high, silt accumulations at several places, and crumbling canal linings. Breaches in the canal are a frequent problem. The SSNNL chairman admitted as much before losing his cool—“The lining of the canals is only 4 inches thick, it is like pappad. We’ll just have to learn to live with breaches.”

It’s an apathy that filters down the management hierarchy, it seems. While Jhala points out portions of the canal where the lining has given way entirely, the deputy executive engineer in charge of this stretch of the canal, AB Patel, drives up. “What can I do?” he asks, “The canal supplies drinking water further ahead, so supply cannot be stopped even for routine maintenance. Parts of the canal have not been lined, others are decaying. In a few years, all of it may have to be done again.” He is half right; the flow cannot be stopped, but this is because the Gujarat Water Supply Department has failed to construct water storage tanks that could allow the canal to be shut for a few months.

Patel admits that there is no solution in sight: “We have planned out the land acquisition, a survey has been carried out, but you know how complex the procedure is. On the ground, there is no clarity between, say, three brothers as to who owns which piece of land. And then there is the revenue department… who knows how much time they will take? The sub-canals will take at least three years to conceive and build.”

LIMITS OF APATHY

At the very source of the canal where it draws water from the Saurashtra Branch Canal, a glaring breach has been in existence for a year. A recent media report quoted a senior engineer as saying, ‘Vallabhipur Branch Canal has capacity of 2,400 cusec of water, but effectively, it cannot carry even 1,000 cusec because design is very poor and civil work is very shoddy. That would cause breach in the canal. In many canals, even trees and grass have grown, and gates which are meant to regulate the water flow are almost defunct. In fact, most of the canals… cannot carry water as per their prescribed capacity as all of them are heavily silted and have structural deficiencies.’

The irony is heightened by the fact that the Saurashtra Branch Canal is carrying water against the gradient to Saurashtra—five pumping houses are being built to transport this water by using over 250 MW of electricity. As a result, according to Patel, the water going waste at the breach and the water Digvijay Singh Jhala is using to water his brinjals, costs the state litre-for-litre “as much as mineral water”.

As Alagh points out, “The water for Saurashtra and North Gujarat was not part of the original scheme. We had carefully calculated the water available through the project. Once the system is in place, we will find that there is not enough water to provide for this part of the scheme. The water is simply not there, and this will ensure the benefits of the scheme will go down.” At other places, the state has diverted the water flowing in the main canal into rivers such as the Sabarmati. But this is just another way of letting the water flow out to the sea.

The simple truth is that Gujarat is in a bind. The water in the absence of minor canals cannot be released into the network, yet drinking water has to continue to flow. The canal network continues to decay without expanding, and in many places the water farmers are pumping out is meant for drinking purposes downstream. The state government simply does not know how to respond to this scenario.

Its response seems to betray the same paranoia that saw the chairman of the SSNNL blame the NCA for his own failures. In an internal government note on 27 January 2009, the company’s Joint Managing Director RK Tripathy accused ‘certain officials of the SSNNL for working hand-in-glove with Madhya Pradesh by allowing the state’s share to be diverted to the neighbouring state… Instead of providing water to the state’s farmers, the government sent state reserve police (SRP) to Malia, Banaskantha and Mehsana, purportedly to confiscate motors being used by water thieving farmers this year… I believe that the decision not to allow water to be used by farmers, and going so far as to send SRP to confiscate pumps, or not providing drinking water, is against people’s interests. I also think that all this is being done to indirectly help Madhya Pradesh.’

In other words, as the above-quoted letter suggests, Gujarat’s state reserve police has been deployed in the interests of Madhya Pradesh. These are damning words. Yet, Tripathy was subsequently made managing director of SSNNL, a post he currently holds.

The story gets even more complicated. Now that Tripathy has given the go-ahead for farmers to pump out water, the government has again changed its mind—in a meeting last week chaired by BN Nawalawala, advisor on water resources to the chief minister. It has decided to confiscate diesel pumps installed ‘illegally’ by farmers along the Narmada Main Canal and its branches across the state.

In reality, the government will not be able to clamp down on farmers everywhere. To do so will only earn their ire, a far cry from the initial conception of the dam, by which farmers and villages were to be partners in the distribution of water. The idea was that kissan samitis (farmer’s committees) would be set up in villages that stand to gain from the project. According to Alagh, who had helped plan the proposal, “A lot of study had gone into it. For the first time, actual farmer behaviour was used to design a farmer-managed irrigation system. Something went wrong.”

MAZE OF DENIAL

The original idea was that water would be released in the area under each samiti four to five times a season, depending on requirement and the crops that farmers had agreed to grow. Charges would be levied on this basis. The existence of these committees formed the very rationale for the entire network. These were expected to ensure the feasibility of the dhorias (the final links that lead out of sub-canals) that would carry water to the fields of farmers.

As of now, the committees exist only on paper. Asked about this, the chairman of the SSNNL reacted in typical fashion: “Some associations are working well, some are not doing their job well.” On being asked to name one village of his choice in all of Gujarat where one could see the work of such an association, his response was evasive. “Don’t bother me with such things, go ask any of my engineers—they will tell you.”

We go looking for some villages on our own. In the village of Khaingari in Ahmedabad district, water from Narmada has started to flow. Laxmanbhai Bharwar, a Maldhari (tribe of cattle herders), declares himself content with the state of affairs. “The whole village is changing,” he says, “We used to take only one crop, now everyone is planting wheat and rice. In this village we were landowners, but in the neighbouring villages, our tribesmen would travel huge distances with their cattle in search of grazing opportunities…now no one goes anywhere. Everyone here is happy with the government.”

Rajubhai Wagchi has planted 10 bigahs of paddy on his fields. It is a crop no one ever harvested here. He has only one worry—since no association of farmers exists in the village, no one knows when the water will flow, if at all it does. Paddy has been planted close together, awaiting transplantation, but the water stopped flowing three days before we reach the village. He has a small bore well to tide over his immediate crisis, but Meenaben Patel, who owns barely two bighas, has far more to worry about. She and her family have been carrying pots of water from a nearby tank to keep the crop alive. She thinks we are officials and starts pleading with us, “Please get the water started, the crop won’t last much longer.”

FOR SOME RELIEF

It is undeniable that the presence of water in this otherwise arid landscape is nothing short of a miracle. Alagh cannot keep the awe out of his voice when he talks about it. “Have you seen the main canal?” he asks, “It is beautiful. It is the largest irrigation canal in the world, like a river in high flood. No other irrigation canal in the world is even half the size. Never has so much water been available in the entire history of civilisation in Gujarat.”

And never has so much water been allowed to flow waste. The idea was never that this canal would be just another alternate route for water to flow out to the sea. I would say Alagh is right—never have I seen anything quite as beautiful as the clear flow of sweet blue water in this parched landscape. Or quite so tragic.

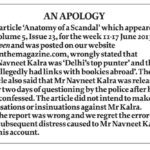

/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Cover-Openomics.jpg)

More Columns

Seven common myths and misconceptions about sleep debunked! Dr. Kriti Soni

Ranveer Allahbadia: Laugh Track or Attack? V Shoba

The Next Moves in Manipur Siddharth Singh