The Viral Success of Online Parody Artists

YouTube could kill TV and movie stars in upper class India, if that hasn't happened already

How can you tell somebody's an IITian within the first ten minutes of meeting him? He tells you so. Arunabh Kumar went to IIT Kharagpur. After failing his first attempt at the Joint Entrance Exam, he took a year off in Kota— the national capital of IIT aspirants—before he got in, and picked up an engineering degree.

At least among smokers outside Toto's bar in Bandra (Mumbai) where we're hanging out, Kumar doesn't need to play the IIT card. He is a filmmaker. Practically everyone around here has seen his latest film, which I'm sure cannot be said for most of the new Hollywood/Bollywood releases. I don't know if he has groupies, but I can see he gets a lot of female attention when he mentions he's the guy who makes the 'Qtiyapa' videos that play on YouTube. He's a rockstar of sorts. He's currently sporting a slight beard, preparing to play Prabhudheva in a forthcoming parody.

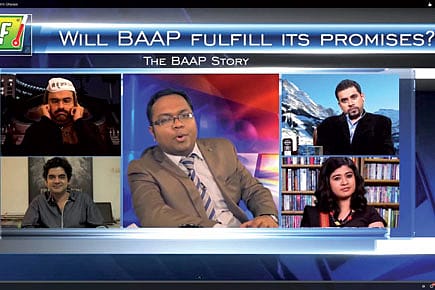

Kumar's last film was called Nation Wants To Know—a spoof on the hyperbolic political drama that takes place every night on prime time television while the nation probably wants to know if we really should be watching TV news on the radio instead. Going by the ratings, these prime time panel discussions on major events of the day are well liked or at least well watched, even as they cost so little to produce: no crew needs to travel too far to gather exclusive footage, reportage isn't necessary, editors can stay home, reporters have to do even less legwork for top ratings.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Roughly the same set of politicians—party spokespersons— appearing on channel after channel couldn't possibly be so impassioned about defending the indefensible every night. Eventually, they begin to sound slightly fake. A new outrage gets manufactured at 9 pm. The performances are first-rate. That's what cameras tend to do—turn us all into posers and actors first. Entertainment is complete. No one I know unfortunately watches these shows for the substance.

Kumar's spoof video is centred on the peppy and hugely popular Arnab Goswami's Times Now show The Newshour, which has more opinion than news, and lasts for much longer than an hour. The original Arnab would be flattered by his imitation on Kumar's send-up. As would Arvind Kejriwal. The smartly-written comic sketch, brilliantly enacted, draws striking parallels between Bollywood and Indian politics.

Kumar had first approached MTV to produce his Bollywood parodies. The gatekeepers at the channel didn't greenlight the concept. Qtiyapa's channel The Viral Fever Videos now has a much stronger subscriber base on YouTube than MTV India or Channel [V]—the original curators of desi cool from almost two decades ago. Qtiyapa videos usually get over half a million views. Nation Wants To Know at 16-minutes-plus became the longest video to go viral in India. I suppose Kumar didn't expect this.

Nobody knows what goes viral on the web. Certainly not Alok Nath, who wakes up one morning to find himself more famous than the sum of his work because someone randomly tweeted a joke on him, which led to more jokes, memes and a viral video. An FMCG company asked me to host a web-based chat show, where its execs wondered if I could make the celebrity guests do something—'Say something, I don't know, make them dance, sing, take their clothes off'—so the interview could go viral. I don't think you can plan this in a boardroom. The pressure is unnecessary. Last checked, there were 60 hours of footage being uploaded every minute on YouTube. I have no idea why a toddler saying "Charlie bit my finger again" has had over 6.6 billion views.

Nation Wants To Know had over 2 million hits in less than a week. The figure is astounding even if you compare it to mainstream media, which is run by major conglomerates, and whose reach is calculated through surveys with relatively low sample sizes—200,000 plus readers for newspapers; about 8,000 homes for television. The results are extrapolated to arrive at numbers that run into millions. You don't guesstimate viewership on the internet. It's a genuine census. I hear corporates can make anything trend, which is such a waste. Everybody can tell the difference between what's really popular and what's a plant.

There are very few people I know who are 35 and under who do any kind of appointment viewing on TV, nobody I know under 30 reads a physical newspaper. The demographic I speak of comprises upper middle-class consumers. Yet, almost all advertising spends go to print and television. Even The Guardian in London, which has most aggressively embraced the internet, gets 75 per cent of its revenues from the printed newspaper. This could be because most decision makers for ad spends are still immigrants to the web, unable to appreciate how the young natives have totally immersed themselves online.

The problem with the internet is also the reason for its global appeal: it is practically free. This shows up in the quality. The bulk of it is piss-poor. The majority of popular stuff is a takeoff on mainstream media. But the access is instant. You don't have to order a copy from a vendor, go to the mall, or sit around with family to watch a show. It's on your cellphone, and chiefly on the office computer, which is where, I'm told, most of the consumption takes place during breaks at work. There is the added pleasure of making a discovery. This has finally begun to create 'new media' stars, whose fame could rival those from television and even blockbuster films.

Kumar's main competitors are a group of comedians who call their YouTube channel All India Bakchod. I used to see them do free stand-up shows at 'Open Mic Nights' in Bandra. They are now celebrities in their own right. From anecdotal evidence, the most popular film review in India could well be the blog Vigil Idiot—that spoofs latest Bollywood releases with stick figure doodles—and KRK, a rabid maverick, and Deshdrohi actor, who trashes big budget flicks on YouTube. Technically, they are not film critics. But then, since we're on technicalities, some of the films they refer to aren't films either. Miss Malini is the go-to person for gossip, and News Laundry the ideal platform to discuss mainstream news. Songs like Mere gand mein danda and Mein kaatil sardar are a much bigger rage than we realise. These are homegrown creations of the internet. Twitter has its own range of celebrities.

Pardon the shameless immodesty, but in over a decade of writing for popular publications, being a guest on news programmes and hosting film-based shows on various national TV stations, over the past week or so, I haven't been to a party or a random bar where someone or the other hasn't given me a confused but knowing stare. Before they can finish murmuring, "I think I've seen you somewhere…," I warmly help them out, "Yeah, I'm the same guy who did that 10 second cameo in that Qtiyapa Aurnob video." So be it. I just didn't know it. That's the power of YouTube, I guess.