Pakistan As A Distraction

Few will disagree that putting India on a path of sustained high economic growth is New Delhi's most important policy objective. Economic growth is the best known method to extract millions out of poverty and put them on the march to prosperity. This is what we learn from Europe, the United States, East Asia and China over the last 300 years. This is also what we know from our own— albeit reluctant, apologetic and meandering—experience of the past two decades.

A compelling explanation for Narendra Modi's remarkable ride to power in the 2014 General Election is the promise that his government will deliver on Middle India's aspirations for growth, prosperity and transformation. More than efficiency improvements, limiting high-level corruption and big government programmes to spur investment and employment, the economic growth imperative demands that the direction of the ship of state be set towards greater liberalisation and deregulation: from fixing the banking system, to divesting moribund public sector enterprises, to liberalising education, health, labour and land.

One would presume that the favourable global economy, with low prices of commodities and capital, would lead the Modi Government to use it as an opportunity to launch the biggest reforms the country has ever seen. This has not happened thus far, but there is time yet.

None of this has much to do with Pakistan.

Our troubled neighbour is, at worst, a risk that needs to be managed. Indeed, one of the best ways to manage the risk Pakistan poses is to grow the economy quickly. A richer India will have a lot more resources, capabilities and friends, which will make it progressively easier to handle the trouble Pakistan can make.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

India's most powerful Pakistan policy would be 8 per cent economic growth. Regardless of the pious homilies from 'South Asian' solidarists, as of now, it will take at least two decades before we reach a point that our neighbourhood policy will begin to place constraints on India's growth and prosperity.

This is not an argument for isolationism. Rather, it is a pragmatic case for prioritising foreign policy towards countries and issues where there is maximum return on effort. Today this means we must engage the United States, Europe, China, East Asia and the Middle East. Given the limited number of diplomats and civil servants, it makes sense to allocate policy bandwidth to those areas which afford us the strongest chances of achieving our geo-economic goals.

It is therefore nothing short of baffling that the four most recent Indian prime ministers—including the current one—feel compelled to get embroiled in Pakistan policy. It's almost as if the Prime Minister's Office is infected by a Pakistan Peace Process Virus (PPPV) which afflicts the incumbent, no matter how strong, how level-headed he is. It is equally baffling that the lessons from the previous incumbent's tenure are forgotten or set aside by some of the most intelligent strategic thinkers in government. Unfortunately, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has become the latest Indian Prime Minister to suffer the inevitable political consequences of a foray into Pakistan. The problem is not with Modi (or Manmohan Singh, or AB Vajpayee before him). The problem is with Pakistan.

From a geopolitical perspective, there are two Pakistans. The first, represented by Nawaz Sharif, is the putative Islamic Republic of Pakistan. It has all the trappings of a sovereign state—a constitution, a flag, a president, parliament, ministers, a civil service, police, military and so on. Some of these work to some extent. In theory at least, the Pakistani state can, if its survival and security demands, co-exist with the Republic of India.

The second Pakistan, represented by General Raheel Sharif, Hafiz Saeed and a galaxy of unsavoury characters, is what can be described as the military-jihadi complex. It is sometimes referred to as a 'state within a state' or the 'Deep State'. It is better described as a military-jihadi complex because it includes the large parts of the formal military establishment, civil bureaucracy, Islamist organisations, jihadi groups, organised crime syndicates and legitimate businesses. Held together by common interests and common ideology, the military-jihadi complex needs enmity with India to justify its own existence and perpetuate itself.

Between the two, it is the military-jihadi complex that is the more important geopolitical player because it controls strategically salient territory, possesses a nuclear arsenal and operates terrorist infrastructure with international reach. Raheel is the more important Sharif because he is the more dangerous of the two. Nawaz, on the other hand, is a very clever politician who has managed to simultaneously persuade the army, the Islamists, Washington and New Delhi that he can deliver what they each want. He is primarily concerned with his own survival, which requires him to stay in or on the right side of power.

So when New Delhi engages Pakistan, it is like one batsman against two bowlers bowling simultaneously. Just when you think you've played a great shot—a solid defensive one or a flashy hit over the bowler's head—you realise that you've been bowled by the other bowler before you've finished your follow- through. The doppelgänger is always there, even if you declare you aren't going to face him. Even if you ignore him. Even if, as it turns out, you accept that he is a part of the bowling team.

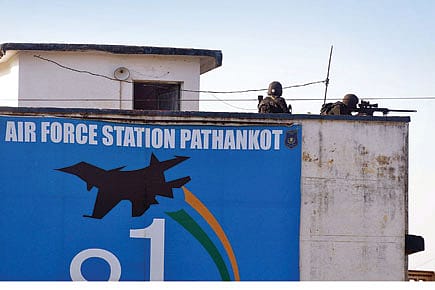

So whenever an Indian prime minister makes a grand political gesture to Pakistan, we receive a stinging attack in reciprocation. The most famous example of this, of course, is Kargil, when General Pervez Musharraf destroyed Vajpayee's outreach to a younger Nawaz Sharif. Those with older memories will recall how Rajiv Gandhi's breakthroughs with Benazir Bhutto were frustrated by the ISI. Similarly, Manmohan Singh's attempts to deal with Musharraf and Asif Zardari were undermined by several subsequent terrorist attacks, with 26/11 being only the most spectacular one. The Indian consulate in Herat was attacked after Modi's grand gesture of inviting Nawaz Sharif to his swearing-in ceremony. The Pathankot attack came after the Prime Minister's unprecedented visit to Lahore to attend Sharif's granddaughter's wedding.

Like in the case of his predecessors, the Lahore trip has left Modi with the unfortunate choice of escalating the tension (and digressing from his more important agenda) or swallowing the blow (and suffering the political consequences).

Shouldn't the knowledge that the Pakistani army might be on board Nawaz Sharif's approach towards India change old calculations? After all, Lieutenant-General Nasir Khan Janjua, Nawaz Sharif's national security advisor, is General Raheel Sharif's man. His meeting with Ajit Doval, his Indian counterpart, in Bangkok cleared the decks for the 'comprehensive bilateral dialogue' between the two countries. Although General Janjua was not present in Lahore when Modi dropped in, it is inconceivable that General Sharif was not kept in the loop by his putative boss. Reading between the lines of some media reports, it is possible that Washington might have signalled to the Indian side that General Raheel will acquiesce in the latest dialogue process. So, wasn't it different this time?

Well, sort of. A decade ago, as his foreign minister and others have attested, General Musharraf, then both president and army chief, was close to signing off on a deal with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Then at the peak of his power, even he was pulled down by other elements in the military-jihadi complex. Similarly, even if—let's give him the benefit of doubt—General Raheel Sharif personally supported the new dialogue with India, the vested interests of the military-jihadi complex weigh against any attempt to improve political ties with India.

It is abundantly clear that political overtures to Pakistan will result in terrorist attacks. It does not matter who is in power. It does not even matter if both the prime minister and army chief back dialogue initiatives. As long as the military-jihadi complex exists, it will be dominant. As long as it is dominant, it will not permit political rapprochement. Even if India were to concede all of Pakistan's territorial claims, the military-jihadi complex will invent new causes to keep the pot boiling.

In other words, the Pakistani military-jihadi complex's interests make it an irreconcilable adversary. Ergo, it ought to be India's goal to weaken, contain and ultimately destroy it. Such an objective is a tall order. Unfortunately, it is unclear if the wisest strategists in New Delhi have adopted this as a long-term national strategy. Going by the wild policy swings from overtures to standoffs, from dossiers-and-lawsuits to periodic ice-breakers, it appears that New Delhi's Pakistan policy is a series of ad hoc, seat-of-the-pants moves driven by events often accompanied by compulsions of Western pressure.

Dialogue is not an end in itself. Unlike with other, normal countries, it is also not merely an instrument to try and resolve outstanding disputes. In the case of Pakistan, the content and pace of dialogue should be part of the overall strategy to rid the planet of the military-jihadi complex, in partnership with countries that have similar interests, and indeed even with right-thinking Pakistanis who seek a better future. Proceeding with dialogue without a consensus on what India's policy objectives are is to put the cart before the bullock.

Earlier Pakistan would flatly deny that it harboured terrorist groups that carried out attacks on Indian soil. After 9/11, the world changed and it had to adopt the stance of demanding proof of this while promising action against the guilty. Going by last week's reports, Nawaz Sharif himself called Narendra Modi and agreed to act against the masterminds of the Pathankot attack. The positions might well have shifted over time, but it would be misleading to see this as progress. The Pakistani government is merely taking positions that it can get away with, defusing the immediate pressure before lapsing back to dilatory tactics. Omar Saeed Sheikh is still in prison awaiting the completion of a legal process. The trial of 26/11 conspirators shows no sign of getting anywhere. Hafiz Saeed and Masood Azhar are addressing public rallies in Pakistan, even as the Pakistani army is supposedly engaged in massive anti-terrorist operations across the country.

For Nawaz Sharif, talk is cheap. Action will be very expensive as he found out in the aftermath of Kargil. It is unlikely therefore that his government will arrest jihadi leaders. If he does, it is unlikely that his government will remain in power for long. It is far easier for Pakistani officials to string along New Delhi, Washington and other capitals with hints of contrition and promises of cooperation.

In the face of all this, what should New Delhi do? Patience is an important ingredient here. Our leaders must be prepared to wait as long as it takes for Pakistan to sort itself out. It is a false dichotomy that the alternative to dialogue is war. There are a range of options in the middle that India has not sufficiently explored.

First, New Delhi's primary interlocutors on Pakistan policy are in Washington, Beijing and Riyadh. India should engage the powers that bankroll and bail out Pakistan with more carrots and a few sticks. With high economic growth, we can leverage our economic strength to get these countries to keep the military- jihadi complex in check. India can leverage its status as the world's biggest arms purchaser, one of its biggest oil importers and a key player in multilateral negotiations in trade and environment to work out the quid pro quo.

Second, there is a lot to be said for a more serious approach to the political economy on our borders. From Punjab to Arunachal Pradesh, from the Rann of Kutch to the Palk Strait, our land and water borders are enmeshed in smuggling and other illicit activity. Corruption and complicity of civilian and military personnel on these borders creates pathways that have been used by terrorists and militants to enter Indian territory. We do not need dialogue with Pakistan to put our own house in order.

Third, astute use of the size of the Indian market can be used to make segments of the Pakistani civil and military elite dependent on India. For instance, there is a case for India to unilaterally free up the remaining barriers to imports from Pakistan. At the margin, the risk of jeopardising their financial interests might cause rich and powerful Pakistanis to weigh in on the military-jihadi complex.

Fourth, a low-key dialogue between officials on various bilateral issues can continue. This could even include a more formal conversation between India's national security officials and the Pakistani army. Developing and keeping open lines of communication is sensible, as long as it remains low-key and shorn of high expectations.

Finally, neither the Union Government nor the government of Jammu & Kashmir state seem to be moving purposefully to bridge the affective divide in the Kashmir Valley and its surroundings. This is both fortunately and unfortunately in the realm of our domestic politics. Even so, the more we move towards a modus vivendi in the state, the less relevant Pakistan will be to the issue. The gains that religious chauvinism has made over the past few years will first have to be reversed for this to happen.

The correlation between a grand Indian prime ministerial gesture and a vicious Pakistani terrorist response is strong enough to warrant caution and circumspection. Modi is the first Prime Minister in a long time to bring dynamism and personal attention to foreign policy—unfortunately, he risked it on an issue that he ought not to have. He should have chosen to—and going forward, he must—leave the handling of Pakistan policy to no higher a level than the national security advisor. Whether it is pursuing dialogue or its opposite, limit it to civil servants and diplomats. The less the political capital invested in Pakistan, the better it is.

India needs Modi to use his political capital to launch economic reforms and get us onto the bullet train to prosperity. It will be a pity if he is weakened due to an unnecessary wild-goose chase that went wrong.