Mind the Gap

Computers can send a man to the moon, but it takes humans to marvel at the truly marvellous.

'Any effectively generated theory capable of expressing elementary arithmetic cannot be both consistent and complete. In particular, for any consistent, effectively generated formal theory that proves certain basic arithmetic truths, there is an arithmetical statement that is true, but not provable in the theory.' That is Austrian-American logician Kurt Godel's First Incompleteness Theorem. What it simply means is that a system cannot know itself completely. To put it even simpler, we can never know ourselves completely. The mind cannot ever know the mind absolutely. The world cannot know the world. This foundational mathematical theorem was proposed in 1931 and has not been disproved.

In fact, it's amazing how so much of science tells us that we cannot know everything. Take Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, one of the core theories of quantum physics. What it says is that it is impossible to determine simultaneously both the position and velocity of an electron or any other particle with any great degree of accuracy or certainty. In fact, the more precisely you know one attribute, the less precisely will you know the other.

In 1989, British physicist Sir Roger Penrose published The Emperor's New Mind, on the connection between fundamental physics and consciousness. He argued that known laws of physics are inadequate to explain the phenomenon of consciousness. He believed the present computer is unable to have intelligence because it is an algorithmically deterministic system. He argues against the viewpoint that the rational processes of the mind are algorithmic and can be duplicated by a sufficiently complex computer. Thought cannot be simulated in the ways we've been programming our computers till now. There's something more to it than pure logic and maths.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

But for decades, computer scientists have railed against this concept. They have argued that, sure, the human brain (and mind) is a damn complex thing, but given sufficient processing power in our computer, we can replicate it artificially. I think this is scientific hubris, but the field of Artificial Intelligence got heavy funding during the 1960s and 1970s, especially from the US Department of Defense. But over the years, it seemed there was no future for this. Computers would not be able to think, forget about feeling emotions. Artificial Intelligence research was revived in the 1990s as 'expert systems', but they are essentially massive data processing algorithms that go through historical information, analyse it through formulae fed into them and throw up 'decisions'. But we are as far away from building intuition in computers as we ever were.

Can human intelligence be broken down to specific sub-systems so that it can all be mapped out? You can feed the machine data, but can you give it experience, the prism through which we process all our data and, okay, make mistakes? Computers (if all the hardware and software are working fine) can't make errors, but we can make mistakes. And we are fortunate for that. On 28 September 1928, a Scottish scientist called Alexander Fleming, in St Mary's Hospital in London, noticed a petri dish containing a plate culture he had mistakenly left open, which was contaminated by blue-green mould, which had formed a visible growth. He grew a pure culture and coined the term 'penicillin' to describe it. The microwave oven was discovered accidentally. Percy Spencer, an American engineer, was working on radars in Raytheon when he noticed that a peanut chocolate bar in his pocket had started to melt. The radar had melted his chocolate bar with microwaves. Many great human advances have happened through mistakes.

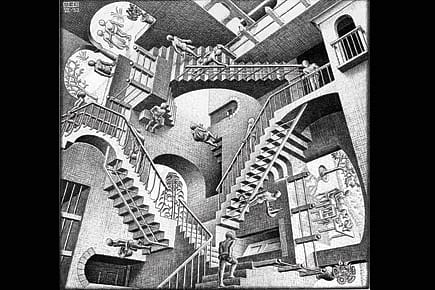

Finally, give the most powerful computer in the world a painting by MC Escher (see above) and wait for it to give you an analysis. My guess is it'll blow a fuse. Computers can send a man to the moon, but that's about it. They can never marvel at things that are impossible. We can. That is what makes us human, different from other animals, and certainly machines.