Do We Really Need a Capital?

The idea of a national capital is not any more meaningful than the idea of national sports and birds.

The idea of a national capital is not any more meaningful than the idea of national sports and birds.

To sit in the backseat of a car and go somewhere with a diagonally distant man called driver, I always thought, was a sign of affluence. But as the newest migrant to Delhi from Bombay, I figure even the austere travel this way almost every day—first mutter the name of the destination in one word to a man who is subdued because it is not his car, and sit isolated from the city and its weather and everything else. It befits the most defining quality of Delhi, which is isolation.

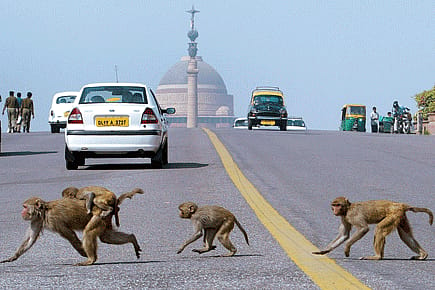

The perfect Delhi moment is when you are sitting in the backseat of a car and passing through an almost endless high wall of an invisible building with an inscrutable purpose, whose name board begins with the words 'Centre for…'. Delhi is a giant archipelago of private islands, both of physical spaces and of those overrated things called ideologies. And if you are not from Delhi, your home seems farthest when you are here. But the question why such a city deserves to be the capital of India is not as meaningful as the question, why do we need a capital in the first place? A capital is a medieval invention.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

There was a time when children used to memorise the national sports of various nations. Argentina's national sport is something called Pato, in which a seeming dog catcher rides on a horse. France's national sport, at least I remember vividly though I cannot find an affirmation on the net, was car racing. But football, which is not the official sport of any country probably because of it being a British invention, has made the entire list of national sports look absurd. Similarly, the natural forces of modernity are increasingly challenging the idea of a capital.

Delhi has an enfeebled hold over the politics of most regions of the country today. Local issues dominate campaigns even in the general elections. An MLA is being seen as more powerful than an MP. Newspapers reflect this reality, and if television news has to cease to look stupid to those outside Delhi, its studios have to accept the truth that people are not interested in what Delhi thinks is news. Also, businesses today do not have to look towards the capital as often as before. But still, what is so wrong in having a capital?

The concentration of power in Delhi generously funds its mediocre. What separates some think tanks in Delhi from fraud is a matter of language. Dim academics and networked activists thrive because they live in Delhi.

Also, the Indian publishing industry, which often asks itself how it can make Indians read more books, should first ask if there is a good reason why it is based in Delhi, and why it publishes so many from Delhi (because they are acquaintances of the commissioning editors), and why the rest of the country should read some eggheads sitting in Delhi. It is also important to ask why a Tamilian in Chennai never writes a book about his quest for something called Indiannness, while an NRI who lands in Delhi is most likely to do just that. That is what Delhi does, it gives its writers the delusion that they are at the centre of a civilisation, and they believe they have to write something important, a dreary story with a giant theme.

The Hindi film industry, which is concentrated in Bombay, exhibits a similar character. It rewards its no-talent insiders. Old stars cohabit and make new stars, who will in turn make more stars. Ancient Punjabi families flog the same stories, someone called Sameer writes every song, then everybody out there wonders why most of the films flop. If we are lucky, a time will soon come when what is called Bollywood collapses and Hindi cinema is made in several cities of the country. But it is foolish to expect the death of the capital anytime soon. So, sadly, a time will never come when a national newsmagazine would be headquartered in Goa.