The Fault in Their Stars

ONE OF THE favourite sports journalistic tropes is the setting up of a player, preferably a great, in the larger context of the aspirations of the country. The idea that you begin with the simple-enough story of the rise of this genius, and you keep pulling on that thread and before long you have the entire social tapestry. Kids growing up in the 90s anywhere in India would later be told how Sachin Tendulkar came to symbolise their generation; that of post- liberalisation India. It does make for good copy, whether or not the assertion is true. It is the kind of story you would want to believe in, lending as it does a respectable sheen to more complicated feelings about identity and nationalism.

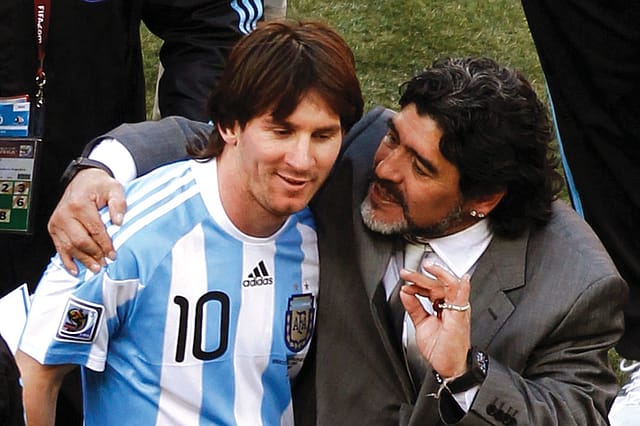

With Lionel Messi, on the first signs of a tug, what (or, rather who) tumbles out in conversations is Diego Armando Maradona. ('Complicated Tango' is the New York Times description of the association.) It seems you cannot mention Messi without bringing up Maradona, and after the pleasantries ('Yes, they are both great players'), there is always the lingering feeling that, with Messi, despite his tremendous success at the club level, there is a debt that remains unpaid to the country. Another NYT article runs with the uncompromising headline of 'In Argentina, Messi is not as loved as Maradona'.

Argentine writer Eduardo Sacheri, in his article No Es Tu Culpa (It Is Not Your Fault), makes a point about how this need to build narratives around heroes gets in the way of appreciating someone like Messi as he is, or deserves to be. Sacheri is the author of the book on which was made The Secret in Their Eyes (2009), which remains only the second Argentine movie to win an Oscar. The author also collaborated on its script. A particularly memorable sequence is pictured in the stadium of club side Racing. An aerial shot tracks a passage of play in which the ball pings off the crossbar and into the crowd, and seamlessly, we are with the hero Ricardo Darin and his side-kick, on the lookout for a suspect in the crowd. Though he left Argentina at the age of 13 and has practically lived in Spain since, it is said that Messi retains the accent of his native Rosario and counts Darin as his favourite actor.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Riffing on the 'It is not your fault' scene from Goodwill Hunting, Sacheri in No Es Tu Culpa plays the shrink to Argentina's obsession with Messi, or more exactly, Messi leading Argentina to World Cup glory and matching Maradona. He insists it's not Messi's fault that the country isn't coming out of a dictatorship or a disastrous war, as was the case with Maradona in 1986, it is not his fault that the two had different personalities—within the same conversation, people mention Messi as a role model for youngsters while simultaneously yearning for the spirit of Maradona, his viveza creollo, the street- smartness and disregard for rules, to take hold of the national side (for anyone familiar with fandom, this holding of contradictory beliefs will not come across as a surprise), and that it is a disservice to compare a player whose career was done and over with that of someone who still had plenty left to give (the article was written when Messi was in his early 20s).

La Nacion, one of Argentina's leading dailies, runs a grim info graphic under the headline: 'World Cups and crisis, the constants that mark Argentina's history', listing World Cup years with the corresponding domestic catastrophe: 1974 and the death of General Juan Perón, 1978 and the military dictatorship, 1982 and the war over the disputed Malvinas/Falkland Islands, 1990 and hyperinflation, 2002 and the sovereign default and economic crisis that plunged millions of middle-class Argentines into poverty.

In May 2018, Argentina went back to seeking IMF assistance after the peso fell by more than 20 per cent. The decision of Argentina's President Mauricio Macri to seek IMF help to restructure the country's external debt (which was becoming more difficult to pay back after the devaluation) and calm the financial markets has been met with a lot of scepticism. The IMF and its conditionalities are believed by many to have exacerbated the economic woes of the country, leading to the default, the crisis and corralito (the freezing of bank accounts) of 2001. The failure to pay creditors back locked Argentina out of the international debt market. Unsurprisingly, a TV commentator uses a football analogy to make his point. "The referee blows for a penalty. Even if you don't agree, you concede the goal and play on. You don't walk out of the World Cup in protest." To further complicate things, inflation in 2018 is expected to be over 30 per cent. In 2017, it was 24 per cent. In 2016, it was above 40 per cent. The years before that, inflation was so high that the country's then government simply decided not to publish the data, it is said.

The weakening peso and complicated history with the IMF brought several thousand protestors on to the streets. An Argentine sports journalist remarks wryly that Messi just needs to win the World Cup, and a report he has filed opens with an Earl Warren quote ("I always turn to the sports pages first, which records people's accomplishments. The front page has nothing but man's failures").

It is not perhaps the lack of a crisis (or World Cup win) that holds the Messi myth back, but the fact that though still alive, Maradona is primarily remembered while Messi is experienced. Which is to say, in remembrance, Maradona belongs to an era. His later day shenanigans do not really matter. He is relived through the words of writers, through songs and movies. Sacheri, Eduardo Galeano, Roberto Fontanarrosa and Osvaldo Soriano (whose vignette on El Diego remains my favourite), to name a few, have written and spoken about Maradona extensively.

Soriano's story goes like this. The author runs into Maradona in a bar in Rome and feigns indifference to the star's stardom. It works, and Maradona places an orange on his head and in a few seconds makes it dance and bounce over every curve of his body without dropping it once. He turns around and asks the writer how many times the orange touched his hand. "Never," shouts Soriano. "No, once," replies Maradona with a grin. "But there is no referee in the world quick enough for me." The anecdote is prominently fixed in the Soriano universe. It may well be true. There is no way to find out.

THE WIKIPEDIA ENTRY on Maradona lists 11 songs and three movies in his honour among plenty more. I have met people who recalled verbatim the frantic, hallucinatory commentary of the Uruguayan Victor Hugo Moralez who happened to be on air the day Maradona scored the double against England in the 1986 World Cup. The English translation, inadequate and soul-killing, as Moralez calls it on air during the second of the two goals, widely considered 'the goal of the century', runs:

"There he has the ball, Maradona. There are two marking him. He steps on the ball. He sets off to the right, the genius of world football. He can pass it to Burruchaga, but Maradona forever! Genius, genius, genius, tá, tá, tá, gol, goool goooooooool! I want to cry, dear God, long live football! Golazoo! Diegol! Maradona! This is to cry for, so pardon me. Maradona, on a memorable run, in a play for all time. The cosmic kite, which planet did you come from? To leave in your wake so many Englishmen, so that the land is a clenched fist, screaming for Argentina! Argentina 2, England 0. Diegol, Diegol. Diego Armando Maradona. Thank you God, for football, for Maradona, for these tears."

In contrast, in the must-win World Cup qualifier this year against Ecuador, as Messi dragged Argentina into the lead after having conceded in the first minute, the commentator on national television finds his world shrink. "Mesiiiii, gol, gol gol! Messi, Messi, Messi, fútbol, fútbol, fútbol." With Maradona, the joy of watching him play was more or less restricted to experiencing it live or through radio or TV, and later, if lucky, to catching a few of the more memorable moments on VHS tape. The rest was down to recollections, shared memories and the produce of culture, both high-brow and popular. In Messi's case, videos of each of his goals, each feint and swivel are easily available on the internet. The over saturated coverage requires little or no additional commentary.

Messi, of course, is a relatively constant presence on TV, especially during the World Cup season. Beyond the ads for a range of products, from cars to chips (in which he appears comfortable with the camera on), Messi is a part of popular culture in unexpected ways. The morning news speaks of 'Nenes bien' or good kids, used ironically to refer to a band of 20-somethings who held day jobs (one of them even worked for the city government), but on weekends broke into unoccupied houses in the richer suburbs of the city. To break through, they use what the band referred to as 'la gran Messi', their crowbar. A restaurant chef in a cook-off proffers his best offering, a hamburger, as "nuestra ganador, nuestra Messi" (our winner, our Messi). A friend remarks that Messi is not so much seen or experienced as he is consumed.

After the friendly win against Haiti, powered once more by a Messi hattrick, the Argentine squad is ready to leave for Spain (where they would train, travel to have an audience with the Pope ) before travelling to Russia. It is also the day the Upper House is to pass a resolution to cut back on sky- rocketing utility prices (gas and light bills, heavily subsidised earlier, have gone up by 10-15 times over two years, comfortably above the rate of inflation or increase in wages in the period). President Macri promises to veto the resolution as the law threatens the government's fiscal consolidation plans.

News coverage (typically, all TV shows on football are high on the passion-meter—five to eight experts disagreeing with each other for the length of the show, mimicking each other as a form of put down) alternates between footage of the Congress and scenes at the Ezeiza international airport in greater Buenos Aires. HD cameras zoom in on Whatsapp conversations of a Congressman readying for the vote ('Lucila threatens to abstain. I think I convinced her,' says a message. 'She is scheming,' comes the reply). At Ezeiza are gathered fans with banners ('Messi, bring us the Cup'), celebrating, chanting. The newscaster announces that the president, even as the Congress was getting ready to vote, would find time to meet the players before they leave the country. Can Messi save the government? So asks the ticker. And then a panellist says not what many would say in Argentina, let alone on national television.

"What is football today? It is a business. They use it to launder black money," says the anchor. "What if Messi wins the World Cup for us? We are where we are and we come back to the same mess." The programme ends, giving way to a broadcast of the lottery results of the province of Buenos Aires. Numbers flash as Black Strobe's Madonna and Me is pumped out in the bacwkground. The scenes at the airport, fans with Messi banners, continue to appear on a screen within the screen.

No Es Tu Culpa, Messi. It is not your fault.

Also Read