‘Vivekananda is unique because he globalises Hinduism’

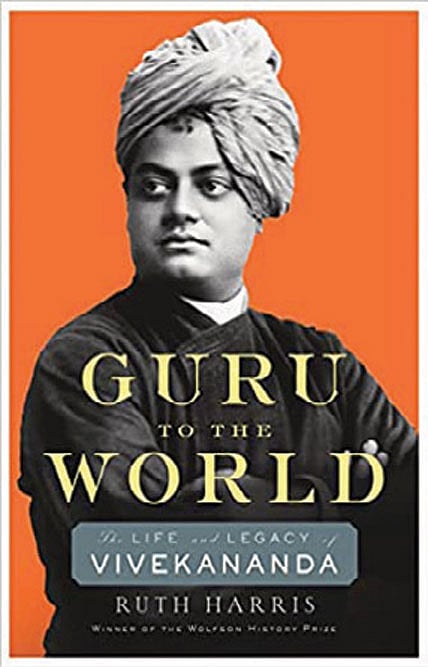

Swami Vivekananda (January 12, 1863-July 4, 1902) emerges onto Indian history like a golden fire—an Agni beset upon the despair-filled forests of late 19th-century India. So incandescent was his presence that nearly 120 years after it ceased to burnish in person the world of religious thought, a careful observer can still glean much from his dimming but luminous halo. But Vivekananda was also a man, a teacher, a member of a colonised society, who was born into a particular moment of Indian history with its own social dynamics, vocabularies of self-understanding, and imaginaries about horizons to aspire for. Historian and academic Ruth Harris’ new biography, Guru to the World: The Life and Legacy of Vivekananda (Belknap Press, 560 pages, ₹799), an imprint of Harvard University Press and imported by HarperCollins, is an effort to excavate the man buried under a century-long mudslide of readings and misreadings. Excerpts from a conversation on Vivekananda, not as a philosopher or theologian but as a life thrown into history.

How must we think of Swami Vivekananda? Is he a 19th-century figure reacting to the first wave of globalisation that arguably began in the 1850s? Is he a 20th-century figure who foreshadowed a revivalist strain in Indian consciousness and has run out of relevance? Or is he a prophetic figure whose speeches and writings will annotate Hindu and religious thought in the decades to come?

The book was premised on the idea that it was about Swami Vivekananda being a late-19th century figure and very much a part of his time. I was trying to understand his life not from our present era, but to place him in the world of the 1893 Parliament, of “mind control”, healing, and Orientalism, as well as the emergence of American Pragmatism, Christian Science and theosophy. To understand what it meant, both for him and those who heard him. And it took a lot of historical imagination because it’s not only Vivekananda whose persona has been overlain with myth and legend. Western women (who were his friends and acolytes) and people like William James (the American philosopher and psychologist) equally had a cliché-ridden vision of the ‘Oriental’ and Indian metaphysician. They were surprised by this man who had read what they had read, and who easily engaged with their concerns, while trying to share his own unaccustomed teachings. I felt that this was my job as a historian to understand him both in his Indian world and in his global context, while also connecting the two. I also wanted to say what he said, because I find people attribute things to him that he really didn’t say.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Freud was born on May 6, 1856; Vivekananda on January 12, 1863; Gandhi on October 2, 1869; and finally Einstein on March 14, 1879. Can we think of these figures as a cohort? If yes, what sort of underlying currents—or to use Raymond Williams’ phrase “the structure of feeling”—were at work by the time Vivekananda appears on the scene?

There was indeed a cohort, and they all sought to encompass relativism within universalism. And these men, including Einstein, were all interested in the ethical ramifications of their thought and believed they were seeking “Truth”. And yet, all, also, hoped that this Truth somehow would encompass many truths, and especially the relativism that came out of their experiences, investigations, and experiments. I think that Vivekananda is especially important because he’s the one who most often and very early speaks repeatedly about unity and diversity and the possibility of their interchangeability. They are all interested also in the relationship between consciousness and cosmic consciousness. Freud is also interested in the unconscious of the individual and how it links to universal mythologies, as much as he wants to link them both to lower levels of reaction and instinct. And that’s certainly true of Jung. All were interested in the interrelations between philosophy, the natural sciences, and spirituality. And it’s certainly true of Vivekananda as he deals with ideas emerging about the “unconscious” and then translates the emerging psychological discourse into a discussion about what he called “‘superconsciousness”. How you deal with what’s deeper within individuals and in cultures and then try to go beyond individuals and cultures. They’re all preoccupied with these issues.

Arguably, after 1902 when Vivekananda dies, without Sister Nivedita’s efforts, perhaps he might have faded away from the emergent Indian middle class’ mind. Her reifying of Vivekananda’s persona in the public imagination has such a huge part in creating our collective memory of him.

It is for this reason that I include so much about Sister Nivedita, for it is almost impossible for us to separate Vivekananda from her vision of him. One of the problems again is: How do we approach the relationship of his key ideas to his own doubts? And that’s the thing. There are so many doubts in him about whether he’s taking the right path—which makes part of your question [to come later] about why he so often pulled people to the middle way. What I do find so interesting about Vivekananda is that, like Gandhi, like Freud, they all had very socially conservative views of women. I know less about Einstein, but the others were very disturbed by female sexuality. And that’s very evident in their writings. But at the same time they are remarkable for the way they take women seriously. So we have to come to grips with men who hold views of women that we might now find discomfiting but who nonetheless took women very seriously, both as idealisations in their thought but also as practical helpers in their rise and legacy. They can’t do it alone. They certainly cannot.

In the West, he called for tolerance of worldviews—that is, asking Protestant Evangelism to see the world and its diversities. And in India, he asked his brother-monks to allow “public women” (sex workers) to worship Ramakrishna as their guru. Here, in a sense, like the Buddha, he spoke different truths to different audiences—all in hopes of improving welfare.

I thought that was an extraordinary insight you had. Mostly when people write about Vivekananda and the Buddha—they have Indological concerns and hence are preoccupied with tracing metaphysical and spiritual connections. But in asking your question about the Buddha, you may be onto something. In addressing different audiences in different ways, he seemed to employ the Buddha’s method of skilful speech and to draw people away from extremes.

Upāyakaushala…

That’s the first thing. But the second thing is the impact of the middle way of Buddhism in his thinking—it is stronger perhaps than we ever realised. Because of this in the West, he’s been seen as a counter-preacher [against Protestant Christianity], against materialism, violence, and fanaticism. But in India, he preached against what he saw as weakness, timidity, and imitation. I would add though that there is an important difference between a counter-preacher and a “skilful speaker”. The latter suggests adeptness and compassion and the other adversarial speech. He constantly sought to straddle the two techniques by both encouraging and scolding and, like a ‘good’ guru, prescribing different disciplines for different people.

In Vivekananda’s story, nobody is more singular than Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. His mystical ways included excesses, abandonments, ambiguous ideas on sexuality and gender identities, claims that he was menstruating and so on—and amid all this is clearly a profound religiosity unlike any we see. But before we go farther, historically speaking, is Ramakrishna a singular persona in modern Indian religious histories? Or was he merely a spiritual-savant of the kind that appear periodically and attempt to break down every barrier—social, emotional, and cognitive—that there is?

I think it’s the latter. For a person who’s a novice, like me, to encounter Ramakrishna was remarkable. Many may think of him as strange, but I think he’s remarkable. Of course, he’s also disturbing because of the stories of his life-defying spiritual trials. And he may even offend contemporary sensibilities. But I would say that Ramakrishna is rare but he is not unique. There are other famous Hindu mystics, hence so many who saw him during his trials thought he was like Chaitanya. There are precedents in Hindu tradition to Ramakrishna, even if he crafted his message in his own way. Ramakrishna may seem strange to us today, above all, because of his insistence on being a baby. But the way he became a baby spoke a kind of all-inclusive truth. He emphasised babyhood precisely because it was a universal human state—before religion, culture, and hierarchy imposed their transformations and created diversity. This understanding or intuition—whatever you want to call it—was extraordinary. And yet it’s integral to many ‘Hindu traditions’ both in its openness to other paths and in the way it sought to envelop and encompass those traditions.

But Vivekananda is unique because he globalises Hinduism. And whether that’s good or bad is open, and remains open, to debate. At the time, of course, the orthodox hated what he was doing—the whole idea that one would engage in the world in the way he suggested was a terrible transgression, especially for a sannyasin. He seems at intervals to be almost worldly in the way he institutionalises, and yet his vision was often radical, and its articulation unprecedented.

But then there’s a deeper, or harder, question that I have thought about which is not about the external aspects of Ramakrishna and all that he did in the world. It is about the deep and profound love and compassion that Ramakrishna shows towards the world and instructs Vivekananda to see as well. There is that episode about Vivekananda mentioning kirtan music having no rhythm but Ramakrishna corrects him, helps him see something deeper, emotional. He says, “What are you saying! There is such feeling of compassion in them—that's why people like them.” It is as if he wants to remove from Vivekananda the burden of Reason when he says, “As long as there is reasoning, one cannot attain God. You were reasoning. I didn’t like it.” This is very far from the world of the Brahmo Samaj or colonial Christianity or middle-class Bengali life. Was this ability to demonstrate the ‘radicalism’ of love itself—a self-devouring sublimation, if you will—that ultimately brought young Narendranath Dutta (and later Vivekananda) to Ramakrishna?

Yes, absolutely. And I really believe that it’s hard as a historian to talk about these passions and relationships and yet it is central to my account. Historians often think such questions are outside their purview—they would say that “love” cannot be the centre of historical enquiry. They might feel that “It’s so airy, fairy, it’s so touchy, feely.” But in talking of Ramakrishna’s love for Vivekananda, I am only reiterating what Vivekananda said himself: [paraphrase] “no one loved me like this not even my parents.” He constantly remarks how this love changed his life. And you know, you feel the sincerity of this. So there’s that. There’s also the responsibility. Ramakrishna is a baby and he says, you must take care of me. There is a filial connection that inverts the guru-disciple relationship and confirms it at the same time. Vivekananda came to believe that Brahmoism and its sedate rationality simply could not offer such transcendent experience. Brahmoism also evoked in him a sense of terrible loss—because Indians had to give up so much, including family traditions and images. He acknowledged that without that, without Ramakrishna, he would have been a Brahmo in Kolkata, and he would have been smart (and successful in life). But you know he wanted more than that. He really did. And I do think spiritual ambition plays an important role in his life course. Spiritual ambition is powerful. We must imagine it.

Can we talk briefly about the debates between Vivekananda and William James, the great American psychologist and philosopher of Pragmatism?

The debate with William James is, in my view, very interesting. James does not write the preface for [Vivekananda’s] Raja Yoga, even though he said he would. But Vivekananda does not think that James “gets” Hinduism. Vivekananda rejected James’ notion (written later) that Hinduism is grounded in a “sumptuousity of security”, that Hindus can’t face reality, that Hindus don’t really have the character to deal with darkness because they are looking for transcendental realisation and liberation from the illusion of temporality. Vivekananda is saying the opposite: it is Christians who are deluded because they separate good and bad. And what Vivekananda says is that you have to see God in the Terrible, hence the devotion to Kali, which he keeps slightly veiled in the West. When he talks to his acolytes, he insists that if you have a bowl of milk and there’s a cork in it, you need to have the cork to float to the top to be able to distinguish between pollution and purity. But you can’t push the “Terrible” into the devil’s domain and deny it. He argues that this separation makes Christians [of 19th century America] unrealistic and unable to accept criticism because they deny their own “badness”. It’s a very extraordinary set of lessons. And although he doesn’t make a big fuss about it, it’s quite a riposte to James who, if you’ve read him, is a wonderful and lively thinker.

Reading the book, and now hearing you, and thinking about the emotional turmoil that they experience, it almost feels like your book is a history of the longings of lonely people—refracted through one man’s life. But effectively, everybody is alone in different ways. Ramakrishna, the American disciples, Sister Nivedita, Ma Sarada… They are all finding ways to connect to each other, to touch each other, which happens through Vivekananda.

I actually think that is what the book is about, even if the attempts to connect with one another are sporadic and not always satisfying. It’s part of this global culture, what Leela Gandhi has called “affective communities”. I speak at some length about the disappointments because we all grew up in apparent cosmopolitanism, but the pandemic and the end of globalisation really showed us how wrongheaded we were in our impressions. Globalisation brings as much disruption as it brings connection. That is not to say that I have no conclusions to offer in my book, but I do not think we can tie things up, that we must accept the ratty edges and difficulties. But there’s nothing except this open to us. These kinds of attempts to connect, to love and not to love, to become ‘frenemies’ without violence—that’s all we have—because we can’t expect more. That’s why I am glad that you found the tone of the book “generous”. The longing is so important because it contributes to what they create together both intellectually and spiritually.

In 1902, when Vivekananda died, was there a sense that his life’s work contained something momentous that was to emerge? Or, was he just simply preparing the grounds for Gandhi to emerge in a different form?

Tricky. I mean, what I always wonder is if he hadn’t died at 39, would it have been Vivekananda instead of Gandhi? Would Vivekananda’s views on Islam change? Would he have reacted like Gandhi to Dalits? Or would it have been something different? And I think, all of this is up in the air. And that’s why I think he’s such an enticing but also provocative figure because he pointedly raises all these issues. And then we don’t see what he does with them. He dies. I do think that he was more committed to universalism and harmony than people realise and that these aspects of his thought have now become effaced. He’s a moveable feast—literally—because you can find so much but never pin it all down. And that’s both the magic of him but also why he remains disorientating and provocative. There are times when he seems to presage our views and other times when he seems reactionary. He is simply appalled by what he sees as the inherent violence in Western Civilisation. And that’s a very Gandhian notion. Except, unlike Gandhi, he does not repudiate science, and he does not repudiate technology. And he does not repudiate anything that can bring people up. These differences are important.

Gandhi famously said, “my life is my message”. Vivekananda, in some sense, lived many lifetimes in his four decades of life. If we put aside present-day political fashions that have attached themselves behind the ship of his life, what do you think we should think about more when we think about Vivekananda?

I really think that we shouldn’t pigeonhole him in the category of “Hindu Revivalism”, which only reiterates many clichés and keeps us at a low level of analysis. What we should think about Vivekananda is: How do we have different visions of the Universal in our world today? That is what he was really grappling with and his attempt to straddle these worlds, hence the constant mention of unity and diversity and the need to “embrace different types of Minds and Methods”. Vivekananda raised the question of the relationship between science and religion in new ways. Yet, that is not how people think about him at all. He and Gandhi shared many ideas. Like Gandhi, Vivekananda also spoke against consumerism, on appetites. And yet the difference between Vivekananda and Gandhi was that Gandhi really did try to shut down the appetite. Vivekananda never could. That’s why he is hurt by those people who tell him that he is not a holy person, because he continues to smoke and enjoy food. But that’s precisely the side of Vivekananda that I appreciate because he was not looking to be a Mahatma. He never thought he was at the same level as Ramakrishna. He never thought he was in the same league as Sarada Devi. These are qualities that I admire. His ambitions were more limited and his humanity publicised. But what would have happened if he’d lived through the Swadeshi movement? That’s the mystery here. It is a life that is almost in preparation.