Beginnings and Alternative Ends

WEHN DOES A pandemic really begin? Was it when the Chinese first realised in a hospital that there was a new virus and kept the knowledge hidden in the hope of containing it in secret? Is it when the world realises with curious interest that there is a ripple in the disease universe thousands of kilometres away? Is it the mild alarm of a first case on home shores? Or is it when, finally, a lockdown is first announced which suddenly turns the spread and danger real and makes everyone a participant in its containment? Even up to a few days before Narendra Modi's announcement of a three-week lockdown, the token Janata curfew was considered by most people as a day of celebration. The beginning of house arrest could count as the psychological beginning of the pandemic. And what then would be the end? Would there be a real end when the virus itself is eliminated? Or the threat of the virus from causing any damage even if it is present, leading to a cosy co-existence, like the common cold or the flu virus, that is the best of both worlds for all species concerned? Will the end also be a psychological event and not a medical one?

In early May, a New York Times article argued that would be the case because for most people the question they are asking when they ask about the pandemic's end is when the fear will end. The article quoted historians who seemed to say what many epidemiologists too have been saying—the end is when mankind learns to live with the virus—as exemplified by this extract: "'When people ask, 'When will this end?,' they are asking about the social ending," said Jeremy Greene, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins. In other words, an end can occur not because a disease has been vanquished but because people grow tired of panic mode and learn to live with a disease. Allan Brandt, a Harvard historian, said something similar was happening with Covid-19: "As we have seen in the debate about opening the economy, many questions about the so-called end are determined not by medical and public health data but by sociopolitical processes." Endings "are very, very messy", said Dora Vargha, a historian at the University of Exeter. "Looking back, we have a weak narrative. For whom does the epidemic end, and who gets to say?"

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

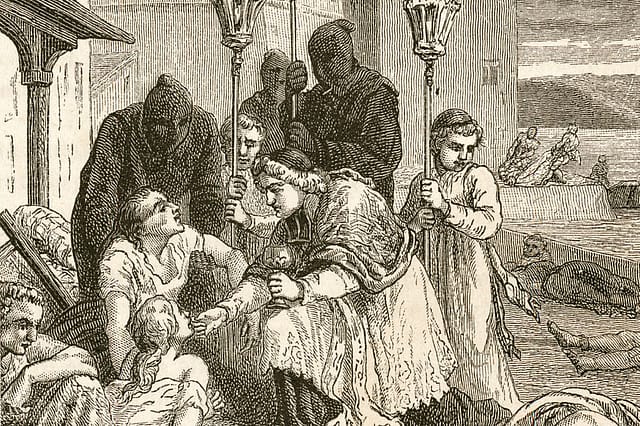

One must always be suspicious when anyone answers a question with a question but the last quote above is a valid point if you look at a disease that changed the course of history more than anything else in the last 1,000 years. The bubonic plague decimated the population of Europe by at least one-third after it first appeared there in 1347, thought to be its starting point from Western history's point of view. The outbreak actually began a couple of decades earlier in China but for most of the world for many centuries, it was irrelevant information. And the end of that particular outbreak—more would follow in later centuries—which lasted for about 50 years has also for long been seen only from the European point of view because all of history was from the lens of their civilisation. One of the plague's fallout is thought to be European domination of the world and the answer of 'who gets to say' is the ones whose memories travel the most.

The selective remembrance can be seen in India itself when it comes to the worst pandemic humanity has ever known—the Spanish flu of 1918. It killed at least 50 million all over the world. The biggest toll was in India: about 18 million could have died. That is every single person who lives in Mumbai today dying off in the space of a year. And yet, who remembers such a calamity even though in families there will often be a memory of someone who died. A few weeks ago, I was speaking to a retired journalist who is in his 70s and he casually mentioned that his grandmother had died after her pregnancy from the Spanish flu. The history of that pandemic was never explored in full here, the oral histories never collated and its horrendous impact remains not even a blip in the collective memory. And it began almost as Covid-19 began, in some far country, with a ship getting the first spreaders into a city and then the virus wreaking havoc in stages. The virus came in three waves. One mild wave in the summer. Then the deadly one that targeted in the northern hemisphere in September; the virus had mutated by then and this was the one responsible for majority of the deaths in the span of just a few months as it went from India's west coast to its east like a Mexican wave. Then finally there was a milder one again in the early months of 1919, but it was now dominant elsewhere in places like European countries. After that it faded away, probably metamorphosing into a benign seasonal flu strain that no one was afraid of any longer. These series of peaks and crests of different intensities are a regular feature of pandemics depending on factors like seasons that affect the transmission or the manner in how people congregate. When a sufficient number of people get it, herd immunity develops and then the pandemic is over. In his book The Rules of Contagion: Why Things Spread—and Why They Stop, Adam Kucharski recounts the work of two scientists, William Kermack and Anderson McKendrick, in the early decades of the last century in finding out how epidemics end and also how the concept of herd immunity was discovered. They did a simulation of an outbreak asking what would happen if a single case began in a population of 10,000. 'The simulated epidemic takes a while to grow because only one person is infectious at the start, but it still peaks within fifty days. And by eighty days, it's all but over. Notice that at the end of the epidemic, there are still some susceptible people left. If everyone had been infected, then all 10,000 people would have eventually ended up in the 'recovered' group. Kermack and McKendrick's model suggests that this doesn't happen: outbreaks can end before everyone picks up the infection. 'An epidemic, in general, comes to an end before the susceptible population has been exhausted,' as they put it.'

In the beginning of the spread, the number of new cases is much more than the number of recoveries. As more and more get infected, the numbers available to get infected start coming down. The pool keeps shrinking, until the recoveries become more than the new cases. Take the results of the serosurvey of Delhi that was just revealed this week. It showed that 23 per cent of the population has been infected. Which means that the virus now has three-fourths of the population to play with. But because there are so many who are already immune, they can't transmit it and are also chainbreakers. Once the idea of herd immunity became known, epidemiologists realised it could be used to manoeuvre the trajectory of the pandemic. Kucharski writes, 'The concept of herd immunity would find popularity several decades later, when people realised it could be a powerful tool for disease control. During an epidemic, people naturally move out of the susceptible group as they become infected. But for many infections, health agencies can move people out of this group deliberately, by vaccinating them. Just as Ross suggested malaria could be controlled without removing every last mosquito, herd immunity makes it possible to control infections without vaccinating the entire population. There are often people who cannot be vaccinated—such as newborn babies or those with compromised immune systems—but herd immunity allows vaccinated people to protect these vulnerable unvaccinated groups as well as themselves. And if diseases can be controlled through vaccination, they can potentially be eliminated from a population. This is why herd immunity has found its way into the heart of epidemic theory. 'The concept has a special aura,' as epidemiologist Paul Fine once put it.' If and when a vaccine for Covid-19 is discovered, it will take months and years to reach all the people on earth, but the principle above will be used to decide on who gets it first. The most vulnerable to its effects, like the elderly, the immunocompromised and health workers, will be first in the line.

Sometimes virus outbreaks end sooner than one expects. Covid-19 is SARS-2 virus. SARS-1 virus also started in China a decade and a half ago and spread to nearby nations and just as the alarm bells went off for a global pandemic, it petered off abruptly. It didn't take Covid-19's scale because it made the infected much more severely ill and so steps could be taken early to contain it from spreading. A Scientific American article said: 'Thanks to aggressive epidemiological tactics such as isolating the sick, quarantining their contacts and implementing social controls, bad outbreaks were limited to a few locations such as Hong Kong and Toronto. This containment was possible because sickness followed infection very quickly and obviously: almost all people with the virus had serious symptoms such as fever and trouble breathing. And they transmitted the virus after getting quite sick, not before. "Most patients with SARS were not that contagious until maybe a week after symptoms appeared," says epidemiologist Benjamin Cowling of the University of Hong Kong. "If they could be identified within that week and put into isolation with good infection control, there wouldn't be onward spread." Containment worked so well there were only 8,098 SARS cases globally and 774 deaths. The world has not seen a case since 2004.'

How will Covid-19 end? It depends on what comes first. If a vaccine works out by end of the year, then give about half a year more for wide enough availability. But even if a vaccine is not found, medicines might make Covid-19 non-lethal, like HIV has become now. And once the fear is over, so is the pandemic. Or there is the third alternative. The virus could mutate to become harmless. Or none of that might happen and over the course of time, enough humans would have been infected for herd immunity to develop all across. Humans will survive and triumph eventually, but time and toll remain the unknowns.