Balakot and the Backstory of Jihad

On the morning of May 6th, 1831, one of the most decisive battles in India's history took place at Balakot, the very site in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa which became a household name after the Indian Air Force destroyed terrorist training camps between 3 am and 3.21 am in the early hours of February 26th. They were not the first fidayeen to be routed in Balakot.

In 1831, an army of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, under the command of his son Sher Singh, destroyed a great force led by Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi before it could enter Punjab on its way to Delhi. Barelvi, the self-styled Sayyid Badshah, had launched a jihad for the restoration of Muslim power, but this time in an Islamist manifestation.

Barelvi was born in 1786 in Rae Bareli, now more famous as a parliamentary constituency. He became an ideological heir of Shah Waliullah, whose theories for Muslim revival after Mughal decline resembled the thinking of his Arabian contemporary, Muhammad bin Abdul Wahab, founder of the Wahabi movement. Waliullah's most famous prescription was what might be called the 'theory of distance' in which he advised Muslims to live so far from Hindus that the former could not see the smoke of the latter's household fires. This was the only way they could avoid falling under Hindu cultural and doctrinaire influence. Once Muslims returned to 'pure' Islam, he said, they would also return to 'pure' power. Those who did not were condemned as apostates, guilty of shirq.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

In 1818, Barelvi proclaimed his manifesto, Sirat ul Mustaqim , or 'The Straight Path', which claimed that Indian Islam had been 'polluted' by both Hinduism and by the syncretism of Sufis. This was why it had lost to the British, who now had the effective control of Delhi, although a feeble Mughal pseudo-emperor still sat on a wobbly throne, reduced to begging for a pension. Muslims had become sinful, commemorating the death anniversaries of Sufi saints in an urs, or singing and dancing at weddings. They could be cleansed only by the heavenly rain of jihad.

Barelvi first went on Hajj, reaching Mecca in May 1822, where his manifesto was translated into Arabic. On his return in 1824, he declared that Hindustan had become a 'House of War', and mobilised a group of some 600 followers, the martial core of which he described as a Muhammadi Order. They left Rae Bareli on January 17th, 1826, and took the long route, via Sind, to the Frontier regions in the north-west, where he hoped to get the support of tribes for his jihad. On January 11th, 1826, he declared himself an Imam and Khalifa. Coins were struck in his name, with the title of Ahmad the Just, 'the glitter of whose sword scatters destruction among infidels'. Such was his success that his army swelled to around 80,000.

The British watched, waited and gave the holy warriors a nickname: Crescentaders. As it turned out, they were slightly less holy than they pretended to be, and achieved a reputation for assault and loot that did not add to their religious lustre. And the tribes did not want to hear instructions that interfered with their local customs, like bathing naked in the river or marrying daughters to the person offering the most dower. Barelvi's attempts to impose an Islamic nizam, or rule, also met resistance in tribes where the chief ruled by traditional consensus.

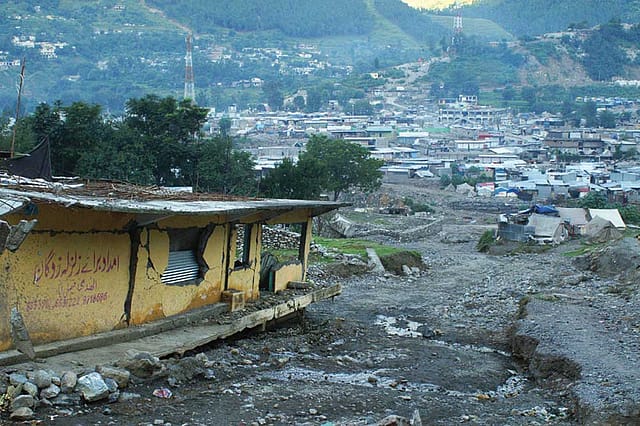

Barelvi chose Balakot as his base because as a hilltop difficult to access, it was considered impregnable. I cannot say whether the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammad jihadis set up their training centres at the same spot, or for the same reasons; for we do not know such specific details as yet. But logic suggests that this might well be true. It was certainly a major strategic consideration for the Sikh army which suddenly appeared at Balakot that May 1831 morning. They had to take a winding uphill route to Barelvi's encampment, which was done under cover of darkness.

One-hundred-and-eighty-eight years later, surprise and the cover of darkness still remain integral to success.

No one saw Barelvi being killed in battle, and, as so often happens, stories began to float; inevitably some of his followers thought he had disappeared and would re-appear. But his head and body were found in different places and are, apparently, buried in Garhi Habibullah and Telhatta. These graves became shrines, attracting religious tourism till today. Those who believe in a jihad for Delhi have a saying: the blood of Balakot runs in their veins.

In 2019, as in 1831, it would be a mistake that the challenge has been extinguished. In the 19th century, the jihad continued till the 1880s.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has thought through his response to Pulwama with careful precision, patience and a measured plan for how to deal with the international reaction. The brilliant pre-dawn strike itself was clean, quick, credible and safe. All aircraft returned safely because of the element of surprise. While terrorists and their mentors, still limited by conventional wisdom, waited for action on the ground, they quite forgot that the air was available for surgery as well.

India's foreign secretary Vijay Gokhale used very clear and concise language to define the chosen parameters to prove that this action was limited to terrorists, and did not extend to the Pakistan military, and there was certainly no overflow into civilian casualties. The operation was "intelligence-led" and that this was a "non-military pre-emptive action". Chatter from the target areas picked by our equipment indicated that Yusuf Azhar, a close relative of the notorious head of Jaish, Maulana Masood Azhar, was on location. Pakistan has repeatedly done nothing about these camps, although they cannot function without the knowledge of sections of the establishment. Our intelligence agencies also learnt that the training for hundreds of suicide bombers would end by mid-April.

This fits into the political calendar of the terrorists as well. It can be surmised that they intended to launch a series of attacks in the middle of India's election process. The political objective of that would be to weaken the image of Prime Minister Modi when the voter goes to the polling booth. Terrorists do not want a strong government in Delhi; and certainly not Modi as Prime Minister. But what they want is not what they will get.

February 26th will go down as a memorable day in the narrative of the long campaign against terrorism. But the war is not over. We can be certain of one thing, though: with Narendra Modi as Prime Minister, Delhi will not be complacent.

Also Read