A Day at the Karachi Litfest

I so look forward to the day when cultural activities in Pakistan can be judged on merit rather than the apparently astonishing fact that they exist to begin with.

I so look forward to the day when cultural activities in Pakistan can be judged on merit rather than the apparently astonishing fact that they exist to begin with.

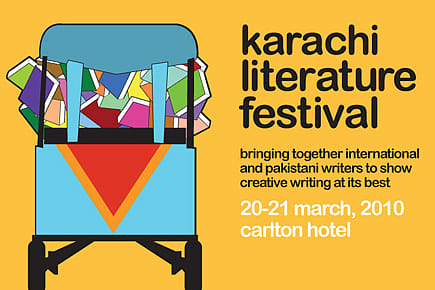

The first Karachi Literature Festival served various purposes, not least of which was providing a calming oasis in the Karachi papers between the headlines 'Bodies Found in Gunny Bags' and 'Man Booked for Wife's Murder'. Held at the distinctly seedy and fairly remote Carlton Hotel, (a place to take note of if one is planning to conduct an adulterous affair with one's secretary), preceded by only three days of modest publicity, it is a testament to the gameliness and enthusiasm of Karachi's reading public that this gathering was fairly well-attended, with some of the bigger names, such as Mohsin Hamid and Mohammed Hanif, filling out the halls.

Organised principally by the Oxford University Press under the aegis of the British Council Pakistan, the two-day event brought together some of Pakistan's best known authors writing in Urdu and English, along with a few Britons of Pakistani origin, NDTV's Sunil Sethi and British biographer Victoria Schofield representing international voices. Most conspicuous by their absence were literary agents and publishers. Pakistani fiction in English may have become sexy abroad but still isn't published domestically. While it's true that the KLF was held at a time when public spaces are steadily receding, it would still have been nice to read more local coverage of it that didn't lean so heavily on the tiresome and increasingly inevitable framework of 'it's a triumph that anything other than terrorism takes place in Pakistan'. I so look forward to the day when cultural activities in Pakistan can be judged on merit rather than the apparently astonishing fact that they exist to begin with.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The weaker sessions were those where the moderators attempted to put words in the authors' mouths, insisting for example, on one occasion, that the act of writing was by necessity a political issue whereas the writer had merely wanted to put out a good yarn. While it's true that the role of literature is far greater than mere entertainment, cultural dialogue in Pakistan quite often squeezes out the role of pleasure entirely, reducing the art of literature to a glorified picket, with fairly essential matters such as writing style left languishing by the wayside.

A session that survived its moderator was called 'Literature and Humour' and featured Sarfraz Manzoor, British Asian columnist, documentarian and author of memoir Greetings from Bury Park: Race, Religion and Rock & Roll. After reading some fairly amusing excerpts from his book, he mentioned a programme he'd made on the topic of comedy in the Muslim world, posing the question why Muslims aren't funny when our mothers are at least as neurotic as those of the Jews. He hypothesised that this was related to a culture that placed great stock in saving face, along with levels of touchiness that didn't encourage humour. This is partly true, and truest when it comes to the enormous sore spot that is religion, which a zealously cultivated hypersensitivity has rendered no laughing matter. The Islamic world, as it stands now, is never going to produce Woody Allen ("Not only is there no God, try finding a plumber on a Sunday") or Groucho Marx, who, during the Crucifixion scene in Jesus Christ Superstar, shouted out, "Well, that's bound to offend the Jews".

That aside, Pakistan at least has a long and accomplished record of comedic writing in the vernacular, and increasingly in writing and performances in English. That this fact hasn't reached Manzoor in England is partly due to the limited amount available in English and crucially, the limited amount that translates well outside of the cultural parameters from which it sprung. Added to this is the sad fact that while the British themselves are known for their dry wit, their appetite for comedy from their immigrant populations hasn't evolved all that much over the years. British Asian comics, Muslims in particular, still cater very much to stereotypes involving second generation British Asians coping with the backwardness of hick parents rooted in the old country. The terribly clever sketch show Goodness Gracious Me pulled it off with great aplomb. Others have not handled this material as well. Attempts at breaking out of this one shtick have proved difficult while the weakest shots at it (portrayals of Asian shopkeepers with funny accents, not to mention the horribly heavy-handed gags that formed the representation of the Bengali community in Zadie Smith's White Teeth) have gone down a storm. The social structure has grown more sophisticated but this clapped out comic formula has failed to do so. The reason for this, I fear, is that by and large the British public are perfectly happy being entertained by their minority communities as long as they're still laughing at them.