Where the Mind Is Without Fear

To be a witness, if not a channel for others’ voices

Kapka Kassabova

Kapka Kassabova

Kapka Kassabova

|

07 Feb, 2019

Kapka Kassabova

|

07 Feb, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/JLF1_1.jpg)

• Ghosts

Few places on earth are more unlike each other than the light-filled Highlands of Scotland where I live and the congested heart of Old Delhi where I came to stay with my partner Tony in a restored haveli-hotel, en route to the Jaipur Literature Festival. I thought I was prepared. As a young writer, I’d visited Delhi for the 2000 Commonwealth Writer’s Prize, and ended staying for two months, travelling across several states. Since then, I’d been to the Kolkata Literary Festival and explored that heartbreak city where the affluent have a court of servants while barefoot men pull rickshaws like oxen. Kolkata was harsh, but still I was unprepared for Old Delhi.

Home to multitudes, yet racked by a singular struggle—the struggle for daily survival—Old Delhi is where the wretched of this earth converge. The stench of desperation permeates the polluted air. Foreign and Indian visitors alike only come for a few hours, with guides and drivers, to see the sights, then escape back to their luxury hotels in New Delhi.

In this city-within-a-city of ghosts, of men and boys from faraway villages whose faces say ‘this is a world without pity’, as you dodge the relentless tooting traffic of muddy streets, you join the scuttling ghosts. Few smile and everyone has a chest infection. Silence only comes with darkness when suddenly, a million people disappear into doorways and only the odd shadow scuttles down a passageway. Some talk of the ‘romance’ of Old Delhi. But there is no romance in urban poverty any more than in war.

Our haveli, an oasis of harmony, gave a taste of Shahjahanabad the way it was before the cleaver of Partition struck. The rarefied comfort of life inside the haveli, complete with soulful qawwali played by musicians, made life outside even bitterer. We longed to peer through the doorways of the many other perilously run-down havelis. Three days before Republic Day, the entire old city was closed off by road blocks, as the Army rehearsed ahead of the parade. It was like a sudden siege. Millions of cars and rickshaws ground to a halt. No signage or warning, no consideration for the residents; drivers and cyclists had to find their own way out of the miasmic labyrinth. But there was no road rage. Just a dull resignation, as in purgatory.

On the rooftops of buildings patched up and layered like tatty quilts, children fly kites barely visible in the smog. Jama Masjid and Lal Qila are wrapped by morning pollution as if by amnesiac fog. Squirrels and pigeons look down on us humans, scurrying rat-like at the bottom of lanes as secretive as ancient wells.

• Bubbles

As soon as we walked through the pink gate of the JLF and into the grounds of Diggi Palace, we were inside a festive bubble. After hours in the cacophonous traffic of Jaipur, it was paradise. True, there are tens of thousands inside the festival grounds, but outside there are millions. Inside, life is suddenly fine again. Scores of school students in uniforms, boys taking selfies, girls queuing up for events and autographs. The atmosphere is carnivalesque. On the first day, a large peepul tree branch fell on lunching delegates, injuring several. That aside, the five-day bonanza of ideas, parties and egos that is the JLF ran smoothly and joyously. In a city where just crossing the road is an ordeal and a country where communicative ambiguity and physical anarchy is a way of life, this is an achievement bordering on the miraculous.

‘Indian magic’ was in fact the theme of one event. While waiting in the queue, a leathery fakir with an artistically unravelling turban approached Tony: “Sir, I am looking for people with magic. Do you have magic?”

We laughed too soon. An actual magician was on stage, who performed impressive sleights of hand.

Easily spotted in the crowd was Sanjoy Roy’s long white hair and twinkly smile. The JLF gives a platform to as many voices and points of views as possible, he said. It’s the way forward. Such platforms are a matter of emergency at this time—when across the world we have become susceptible to forces that try to polarise us along various nationally specific (but universally recognisable) fault lines. This theme defined the festival for me and Tony, and not just because I’m obsessed with borders. There were other, subtler divisions and connections to observe.

The inner circle inside the beautiful Diggi haveli was for the speakers. This is where personalities display themselves, as they do at all glamorous festivals. Some authors complained of being hounded by media. Some quoted from their own books. Some delivered continuous monologues. Yet others were interested and interesting. A journalist from Kerala told us that we must visit that ‘green and red’ state, so different from the rest of the country. He meant verdant and communist. A Rajasthani archaeologist told us that she had 100 cats living with her. I enjoyed conjuring the ghosts of old Delhi with Max Rodenbeck, South Asia bureau chief for The Economist, with whom I was later in conversation about the ghosts of the Balkans.

Is there a collective noun for authors—as in a school of dolphins, a murder of crows? Tony and I wonder, and come up with ‘a vanity of writers’. Dressed in fine fabrics and wearing our world-weary, global faces, we waft past lesser beings, such as the child-like cleaner girl who sits under the stairs when she isn’t cleaning our marbled literary toilet. One writer thought to talk to her, in Hindi. The cleaner was married at 12, gave birth nine months later, and has made it far enough to clean Diggi Palace. The reason she is child-like is malnourishment. She was enjoying herself though, and certainly not complaining. She had her eyes and ears open.

A leathery fakir with an artistically unravelling turban approached Tony: “Sir, I am looking for people with magic. Do you have magic?”

Who will write her story? Or are we all trapped inside our bubbles of expertise and self-regard? Are we here to learn, or display our plumage?

With the fresh eyes of someone who doesn’t often hang out at festivals, Tony noted something: “The actual writers among the writers are few.” Have writers become a minority at literary festivals, and what is an actual writer? Someone who lives a writer’s life, perhaps. Someone for whom writing is not a vanity but a necessity. Being a writer or an artist is a metaphysical and sometimes medical condition—not a career. Seen from the inside, it is more like being a nun than like being a public figure. It takes sacrifice, Tony said. He should know, he works with artists.

It does seem that within my lifetime, the writer who lives a writer’s life has become a quixotic curiosity. The era of the Creative Writing MFA and professorship has usefully coincided with the era of the materially struggling writer. The professorship is new, the struggle is old (the only affluent poets have always been court poets). But we are, I think, softer than our predecessors, perhaps more materialistic too. We don’t like sacrifice. Result: the majority of speakers at book festivals now are academics, politicians, public figures, celebrities—who have written a book, maybe even a good book. But the experiential, free-roaming writer on a shoestring is being ousted by the sedentary, institutionalised writer on a Sabbatical. All of this raises questions about where literature comes from and which stories get told. Questions about deep (not just skin-deep) diversity, originality and heterodoxy. Questions about how to nurture a humanist multi-culture in a global but fracturing world.

The JLF recognises the sometimes invisible inter-connectedness of things, and tries hard to bring together disparate elements and people. A festival can be a crucible of positive change, and the JLF celebrates this. There was glorious live music every night. The old groovers of Indian Ocean with their emotionally charged Music of Hope were a high point for us. Something of the festival’s affirming civilisational vibe will percolate into each private bubble, I am certain. It was enough that one teenager approached me who had already written her first novel and was working her second. She did not ask how to be published. She just said she wanted to be a real writer, and of course she already was.

The most memorable events we saw were with journalists and war correspondents: people who had witnessed important events at great personal cost, or who dared to speak uncomfortable truths on behalf of the rest. They had the look of people surrounded by the ghosts of the world’s dead, long after the news has faded in public memory.

“The world did less than nothing to help Rwanda,” Sam Kiley reminded us, and Jon Lee Anderson posed the rhetorical question that has troubled him over the years: “What is the purpose of being present at tragedies that cannot be prevented?” A question I asked myself while journeying for my book Border. All those people I wanted to help, but couldn’t. The purpose is to be a witness, if not a channel for others’ voices.

“We are aware of how the public imagination can be manipulated, as we are seeing in buffoonish and mendacious leaders,” said Jon Lee Anderson. “Resist these guys’ silent call to violence.”

In a hard-hitting conversation between Rajdeep Sardesai and Madhu Trehan, India’s many ills, old and new, were discussed, including how politicians ‘astutely play’ on people’s entrapment in identity politics, the ‘insipient threat of violence’ behind current political rhetoric, and how, thanks to social media, everyone is ‘inside their echo chamber’.

The cleaner was married at 12, gave birth nine months later, and has made it far enough to clean Diggi Palace

For Tony and me, everything that was laid bare about India had a wider resonance. It was also about Brexit, the phobia against emigrants. It was about the worldwide crisis that manifests as politically polarised nations, societies and families. It was about the need for healing rifts, not turning them into war trenches. India’s problems are unique and also universal (the fomenting of intolerance, the loss of faith in political elites).

“Hinduism’s greatness is in the inclusivity of its philosophy,” Sardesai said—a statement that may once have been obvious, but is once again urgent, “We must reject all radicalism, all violence.”

By the time he read Tagore’s celebrated 100-year-old poem, many in the audience had tears in their eyes. We certainly did. For Brexit Britain, for the Balkans and Eastern Europe, for India and Pakistan and Bangladesh, for Tibet and China, for Syria, Egypt and Libya, for Turkey and the US, for Central America and Venezuela. This is how acute things have become, when hearing a simple truth brings collective tears of recognition. And hope.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments

By narrow domestic walls

Where words come out from the depth of truth…

• Borders and Bridges

Borders, walls and bridges were the urgent theme. Novelists discussed modern migration in fiction. Sanjoy Hazarika, an author specialising in the Northeast border states, talked about his latest non-fiction book Strangers in the Mist (which I am now reading, along with his Rites of Passage—and being reminded that border stories contain universal truths and warnings and if we don’t hear them, we shall repeat them). The fear of being swamped by the other has been with us for a long time. And also the capacity for compassion and understanding.

One of the best literary sessions was on translation, with five outstanding practitioners who among them spoke 20 languages including Nepali which is spoken by 3 million in India alone. Literary translation can make you a living in Europe and the US, but not in South Asia (or, I must add, in European languages with small markets). Literary prizes that reward translation from smaller languages, and therefore non-mainstream stories and subjects, are not only an act of symbolic rebalancing—especially when translations into English are much fewer than translations into other languages (making English the most selfish literary language); bringing a brilliant novel written in Tamil, Pashtun or Portuguese to an international audience, they make our shared culture infinitely richer and more heterodox by breaking language barriers. No one reads a book as intimately as the translator, it was said, not even the author. Daniel Hahn described the terrifying responsibility of literary translation as being faced with a blank page but with someone else’s name on it. Translators should be celebrated on a par with authors: they bridge worlds for the benefit of everyone. A vanity of writers perhaps, but a love-labour of translators.

A strong message of unity came from the panel on the future of South Asia.

“When I talk about the future of Pakistan,” one speaker said, “I deliberately talk about the future of South Asia. South Asia has a much better future together.”

“Nepal has always looked to India for a model of a multi-cultural democracy,” another speaker said, “That’s why the rhetoric of saffronisation has been so disturbing for Nepal.”

It surprised me that there was just one Pakistani writer at the festival. The other one who’d been invited couldn’t get a visa. It reminded me of the Iraqi illustrator invited to the Edinburgh Book Festival who was refused a UK visa three consecutive years, for reasons that can only be described as grotesquely void. We may live in a global world, but visible and invisible borders continue to sabotage our lives. The bureaucratic world of passports and visas has all the brutality of a caste system. A reader came up to me after my event and said: “I live in Europe. Europe thinks of itself as borderless, but try living there with an Indian passport.”

Though we didn’t hear any explicit mentions of Partition, or the horror out of which Bangladesh was born in the 1970s, the ghosts of those events were present at the festival—of the millions of souls who, like their distant counterparts in the Balkans only 20 years ago during the Yugoslav Wars, and the rest of Europe during World War II and the Holocaust, had had to pack a cart with their belongings and cross desolate plains, across newly drawn borders. We are all haunted by our collective past. We are all susceptible to the fearful mindset where walls and fences are first manifested, before they are built on the ground.

After the festival came the anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. We found ourselves in rural Rajasthan, a place of silent sunsets. A Scot and a Bulgarian walking up sandy paths, alongside goats and dogs, reflecting on what Gandhi means to us. In India, Gandhi’s peace message may have been temporarily dislodged by bellicose noise, but no political fashions can change the fact that he is one of humanity’s eternal champions. He reminds us that this perpetually darkening world is also a world perpetually full of light. So long as we will not let anyone walk through our minds with their dirty feet. So long as we remember: where there is love, there is life.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

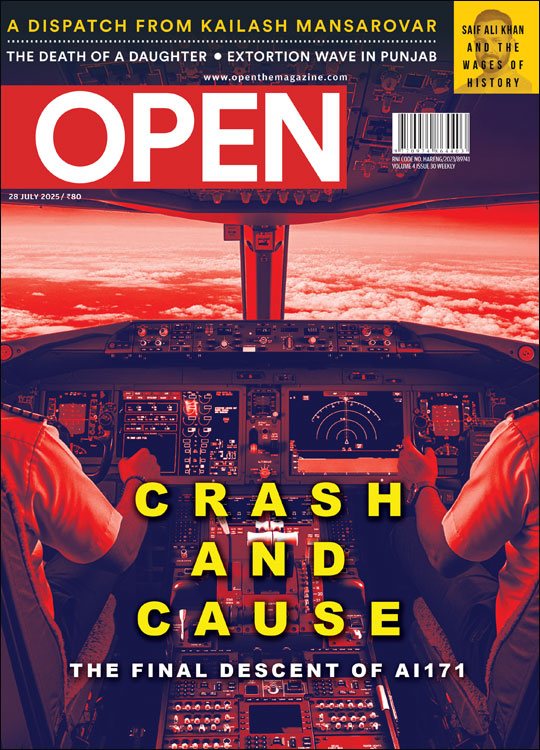

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba