VK Krishna Menon: The Man Behind the Mystique

IN THIS BIOGRAPHY of VK Krishna Menon, Jairam Ramesh rightly points out the irony that though Kerala considers Menon a demigod, he was against the idea of redrawing the state on a linguistic basis. Within the state, he is always forgiven for his sins. People did so even when he was alive. The author explains twice in the book that Menon, Nehru’s sounding board and cabinet colleague, went with the flow and backed then Congress president Indira Gandhi’s bid to get the first communist government of unified Kerala dismissed using Article 356 of the Constitution despite Prime Minister Pandit Nehru’s initial reluctance.

Paradoxically, one of the most memorable photographs of the 1971 Lok Sabha elections is the one from Thiruvananthapuram that has Marxist stalwarts AK Gopalan and EMS Namboodiripad standing alongside Menon, flashing winning smiles. Menon bucked a pro-Congress wave and won as an independent candidate that year with the support of those who were at the receiving end of his diabolical stance as a high-profile Congress leader and confidant of Nehru 12 years earlier. In fact, the Left in India always respected him as a fellow traveller and that explains why communist veterans like Promode Dasgupta and Jyoti Basu were delighted to offer him the Midnapore seat in the 1969 Lok Sabha bypoll in which Menon won, earning, overall, the rare honour of having won elections from three different corners of the country, starting with the victories from Bombay North in 1957 and 1962 as a Congress candidate.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

But in Delhi’s corridors of power, among a large section of bureaucrats, defence beat correspondents and former army officers, he is a reviled figure just as he is revered by a section of career diplomats and others. Even at the height of his glory and power, Menon evoked extreme reactions with his propensity to win friends and foes alike—a trait of his that Ramesh dwells upon at length citing numerous examples all through this 744-page work that draws extensively from newly declassified papers, archives and from personal correspondence available with the Menon family.

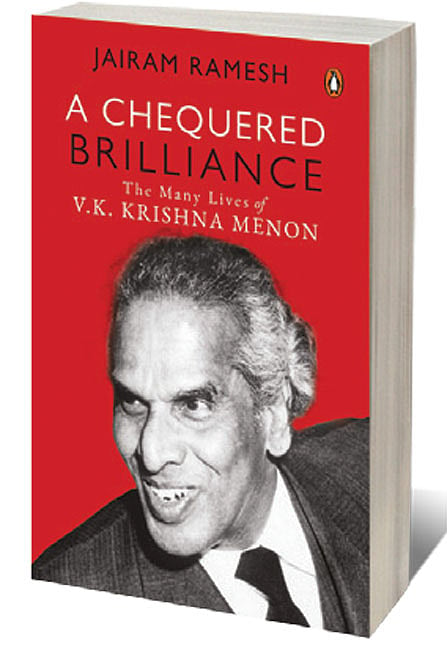

Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of VK Krishna Menon is an apt title for a book about the man often described as ‘global citizen’ thanks to a raft of reasons, including his stellar and controversial stints in London and New York, first as High Commissioner to UK and then as member and leader of the Indian delegation to the United Nations.

A few years ago, a noted editor wondered why we had a road in the national capital named after Menon. The question shocked someone like me who had attended a school founded by Menon, but was par for the course for the editor who started off as a defence and foreign affairs reporter and was perhaps less aware of political history. Congress parliamentarian Ramesh’s book is for both of us, those who are taught to hate Menon and those trained to worship him. Unlike most biographies of the man, this one doesn’t offer punditry about his superman-like qualities and comprehension, but states facts, an outcome of rigorous research starting from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library to Scotland Yard intel records. Trapped between multitudes that make a devil out of him and those who tirelessly whitewash him over certain affinities, this book is a delight for anyone who wants to know the man behind the maze of myriad images.

Ramesh does do justice to Menon (1896-1974) whose failures are often magnified, and achievements overlooked. Menon’s prescience on a range of issues—from the British intent before Partition to the formula for lasting peace between China and India, are explored well. The book addresses the many stages of Menon’s life; his childhood in a rich family in northern Malabar in Kerala; his Madras years; student days and long years of activism in England; milestones in his political career; international fame; epic fall from grace; life after Congress; and his legacy.

As Ramesh writes, ‘…in the 1950s, it was Krishna Menon alone who advocated a negotiated settlement to the Sino-Indian border dispute.’ According to the swap formula he proposed, while China acknowledged India’s claim in the Chumbi Valley, India reciprocated China’s in Aksai Chin. The book offers interesting details of Menon’s own notes on his parleys with Chinese leader Chou En Lai. His three-hour speech—which was later made into a book that the author has dug up—offers great insights into the contentious subject and Menon’s grasp of the situation. The book also scrutinises his follies that put India in a bad spot in the 1962 war. Menon had to resign shortly afterwards to save his mentor and friend Pandit Nehru from further embarrassment, first from the defence portfolio and then from the ministry.

This book, armed with insights from new documents, also looks at certain unforgotten feats of Menon as a UN envoy who has successfully negotiated conflicts and diplomatic rivalries involving the US, China, Korea and other countries. With his tall built, hard, chiseled features and hawk-like gaze that made him hard to miss in a crowd, he was widely networked and had a knack for striking up new ties among diplomats, celebrities and heads of states worldwide. Driven, hardworking and ambitious, Menon often neglected his health to hop across continents, leaving his footprint in one issue after the other as a top-notch diplomat. Featured in the 1950s across American and European dailies, magazines and invited to radio and TV chat shows, Menon, according to former Indian president R Venkatraman who was a delegate to the UN, “was like a seismograph in the United Nations vibrating to every fluctuation in world affairs and registering India’s reactions to each of them. There was such a thing as a Menon Scale, which, like the Richter’s recorded vibrations of different intensity depending on the gravity of the tremor”.

Menon was also cunning, unpredictable and at times wicked. About his marathon eight-hour speech on Kashmir, over two days in February 1957, at the end of which he fainted, his friend and Filipino statesman Carlos Romulo said, “We took him to the room next to the Security Council, gave him smelling salts. He revived, but, of course, that was a ploy. He was a candidate for Parliament in Bombay and he wanted this…. I said, ‘Krishna, you know you won the Oscar award?’”

Menon also attracted hate from people he treated as imperial powers. The book reveals several such instances from his London days when long-time friends turned bitter enemies. The late politician Minoo Masani is one example. It is hinted that the wrath of an American President in 1962 cost him his job as defence minister. Besides, then US ambassador to India JK Galbraith also loathed him. US President Dwight Eisenhower wrote in his diary after meeting Menon, ‘He is a boor because he conceives himself to be intellectually superior and rather coyly presents to cover this under a cloud of excessive humility and modesty. He is a menace because he is a master of twisting words and meanings of others….’

The author also delves into communication between Menon, members of his family, especially his talented sisters and others who were close to him and who knew about many of his love affairs and infatuations, some of which kicked up a storm. For instance, Ramesh quotes Menon’s grandniece Janaki Ram as comparing the relationship he had with a staff at the High Commission in London, Kamala Jaspal, to that between Pygmalion charcters Professor Higgins and Eliza Doolittle. The author also familiarises the reader with events that people who have read Menon’s earlier biographies already know but with newer inputs. Ramesh writes of Menon’s association with Annie Besant who took him under her wing in Madras and offered him an opportunity to grow and land a job in London (Menon addressed her as mother like his associate and famous spiritual guru Jiddu Krishnamurti, also did). We also get to know more about Menon’s father-like devotion and attachment to his professor at the London School of Economics where he was called a “perpetual student” who was destined to acquire many degrees, including an MA and MSc. The book is rich with anecdotes of his association with accomplished peers that include Mohan Kumaramangalam, Feroze Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, PN Haksar and others.

BUT THE MOST hard-hitting part is about the tie between Menon and his most important benefactor, Pandit Nehru, whom he first met in 1935. They hit it off well and Menon would soon become Nehru’s man and publishing agent in London. From their first meeting, all of Nehru’s pre-freedom Europe visits were planned to perfection by Menon who would also play a pivotal role in the publication of his works that invited global acclaim, including his autobiography and Glimpses of World History. It was just the beginning of a friendship that would have a far-reaching impact on India’s freedom, Partition, foreign policy, Constitution, defence preparedness, etcetera. Letters exchanged between Nehru and Menon that the author has used to explain their ties bring to the fore not only the fact that they became soul mates but also lays bare many undercurrents, personal relationships and intrigues within the freedom movement. Ramesh also brings up documents to buttress arguments about how Menon, over the decades, did what he did in the early decades of India’s freedom, including the liberation of Goa from the Portuguese. His proximity to British officials, including prime ministers and viceroys like Mountbatten and his wife Edwina, gave him an advantage, and he warned Nehru of British machinations “that would adversely affect” India’s interests. We get a peek into many such close social and political alliances of Menon’s.

His life as a crusader for India’s freedom in England is narrated with great skill in some chapters. Between 1924 and 1946, he visited India only once in 1932. For more than two decades his work as the leader of the India League was to attract sympathy for the Indian cause among intellectuals (of the order of Bertrand Russell), musicians, celebrities, writers, artists and politicians. His efforts paid off and the pro-India lobby was hyperactive even within government circles thanks to his singular effort. The author captures this part of the man’s life with great finesse.

In resurrecting a figure as complex as Menon—who grew from a school teacher in England to become one of the most photographed (he made it to Time’s cover), talked-about and feared Indians ever, before his mercurial temperament and the penchant for getting into endless troubles brought about his downfall—Ramesh has done a good job. He has put the spotlight on several love affairs of the man known by epithets that include ‘Mephistopheles in a Savile Row suit’, ‘Rasputin’ and so on. Even today, the mystique of Menon, who was so powerful once that he was even seen as a successor to Nehru, continues to grow.