Tishani Doshi: ‘The houses of love we make in our time here are worth singing’

KARTHIKA NAÏR: In the first poem of the book, the portentous Contract, you promise the reader incandescence—and these are no empty words. You also promise her/him fury…. and if there is one quality that runs as Ariadne's thread through Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods (HarperCollins; 96 pages; Rs 399), it is a controlled but palpable, calm and potent rage. I would like to know something about the journey from the 'geography within' of Countries of the Body to the 'space between' (the exploration of relationships and a spiritual locus) that is Everything Begins Elsewhere to this, a crystal almanac wrought from a furnace. When we spoke last, you said you were trying to hone irreverence. Though it isn't just irreverence at play here, there is an almost industrial-strength anger, and despair, yet also the ability to record it all. Is one allowed to delve into a (creative) trigger? At what point in the writing does the trigger enter the consciousness?

And a corollary question. While I am transfixed by the sheer spectrum of fury contained within the covers of this book, I am also intrigued by the centrality of the—often female—body in the collection. Or rather, not so much the body, but the erasure, the decay of the body, which you chronicle with the attention of a clinical pathologist, and even celebrate with tenderness and grim humour. For instance, in How to Be Happy in 101 Days:

Lean backwards and listen to the slippery

bastard of your own arrhythmic heart.

Remind yourself that you feel pain,

therefore you must be alive.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Or, at the end of the scrumptiously mordant To My First White Hairs:

I'd thank you, white hairs,

as a poet should,

but I'm too busy catching

my breath on the stairs.

In that sense, is this book an alter- Sharira? In Chandralekha's duet, the body is the seat of the cosmos, immeasurably powerful, while Girls Are Coming… underscores its finiteness.

TISHANI DOSHI: I think it has to do with being a particular age, and feeling as in the first canto of Dante's Inferno, that you're standing in a dark wood in the middle of your life. This journey that you talk about through my three books is something I can only see in the backward glance. As I was writing these poems, I felt that they were all about irreverence, injecting some element of surrealism, you know, finding the lion in the wardrobe when you were sure of expecting shirts, because I think I wanted to shake up the very real parameters that the body had imposed in the first two collections. But you're completely right—there is fury. Again, not something I'd noticed, until I started collecting the poems. A lot of death. Mortality hangups. I think one of the biggest triggers was moving to live by the sea five years ago. There's this romantic idea of what beach life must be, but the reality of coastal life, at least my coastal life in Tamil Nadu, is that you're brought very close to death. And the presence of decay in the most basic things, like one morning you walk down and the kitchen lights have fallen down because the wires are corroded. The hinges on the gate to the beach give up the ghost every four months. Dolphins, dogs, turtles, awash on the shore, dead. And so watching that slow decomposition makes you wonder naturally about the slow decomposition that's happening inside your own body. We return to the body, yes, and part of what the poems are trying to assert is what you call the alter-Sharira aspect. Again, not something I had given much thought to, but how could it not be playing inside me all the time? To work for 15 years on a dance piece that asserts the body as undying, as the source of infinite energies, and to counter that with the process of ageing, of watching people grow old and die, of loss, of the daily barrage of news which feels more and more apocalyptic, all this dislodges the body's primacy, or attempts to, and the poems I suppose are a way of finding a balance, or treading the water between.

KN: The sea as a harbinger of ends—I had never seen her that way, actually. But, actually, you do spell it out in the wrenching What the Sea Brought In:

Letters of love,

letters of lust, the 1980s, funeral dust.

What the sea brought in was enough

to fill museums—decapitated marigold,

broken nautilus, a betrayed school friend

stuck in the dunes like the legs of

Ozymandias.

A sample of the offerings of the sea… which brings me back to the question of what it is about the sea that impels fealty. There is much that is relinquished here, but not the sea. Could it be, as you say in Jungian Postcard, 'I won't deny, this beach/ brought out strange things in me: impossibilities.' I don't mean to project authorial voice on to the narrator's voice but I am curious about the sea as a constant—not just through Girls but in general—in your writing. Is it the amulet that counters the very decay that it underscores?

TD: There are so many levels to it, and I'm not sure I understand them all, but certainly on a personal level it has to do with memory. I've lived in a city by the sea for most of my life, and my proximity to the ocean has gone from far away to closeby to within biting distance. So, the Bay of Bengal is this constant presence in my life. The happiest childhood memories—a day of swimming and then slumping in the backseat covered in salt and sand, and later, meeting Chandralekha in her house on Number 1 Elliot's Beach Road, and later, moving to a house of my own by the sea. But there's also historical memory, the idea that all life came from the sea, this sense that it is primordial and eternal. This sense that everything we've lost could be returned by the sea. It's a kind of God, really, and I've always treated it as such. With reverence and faith and fear. It seems a precarious kind of life, to live by the ocean, with everything we know about climate change, with the tsunami and floods and cyclones that the Tamil Nadu coast has seen over the past years, it really is a position of great vulnerability, but there's also this aspect of renewing. And I suppose when it comes to poetry, it's the renewal I'm interested in. It's as you say, the amulet that counters the decay. So despite the temporality, despite the unknowing, there's some solace to be had from the knowledge that this has been going and will continue to go.

KN: Speaking of renewal, this collection seems to renew or reinforce the narrator's connection to the world, through time and place, land and sea. The world, willy-nilly, entangles with her voice: whether a past world (the Battle of Plassey, pilgrims of yore, the dead as a community…) or the glowing-hot current planet (Boko Haram, Putin, Aleppo, Bill Cosby, to mention just a handful). Is that too an inevitable part of adulthood, of growing? Or is it more an acknowledgement that one can never really get away from the juggernaut of humanity?

TD: I wrote many of these poems in a kind of seclusion—coastal life, rustic Tamil Nadu setting, only the company of husband and dogs. When you move into a setting like this, it's easy to drift away from the world. So the poems are about making connection, grappling with what you receive from the outside, and this works across time—backward, forward, sideways. Childhood is never far behind. And then there's the inevitable stepping back into the world, the travels, which also inform the poems. Always the reminder that humans are both beautiful and cruel. So a poem like A Fable… for instance took many years to write. It was about being bombarded with news and information and the impossibility of knowing, but it was also asking what if we go into the past, what news would we be able to bring from the future; has being human changed from then to now?

KN: Another thing that Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods does with unblinking resolve is document violence. That of nature against its particles, that of humans against animals, or, in a sense, the violence every living creature seems capable of. It seems to warn you at the outset that this violence is a pre-requisite:

Set out into

the world and prepare to be horrified.

Do not close your eyes. Catch a fish.

Smash its head and watch the life gasp

out of it. Spit the bones into sand.

—How to Be Happy in 101 Days

But the violence that is most extensively alluded to, sometimes dissected meticulously, is violence against women. Violence as a large-scale malaise as in the electrifying titular poem, where

Girls are coming out of the woods, lifting

their broken legs high, leaking secrets

from unfastened thighs, all the lies

whispered by strangers and swimming

coaches, and uncles, especially uncles,

who said spreading would be light

and easy, who put bullets in their chests

and fed their pretty faces to fire,

who sucked the mud clean

off their ribs, and decorated

their coffins with briar.

But, also individual, specific acts of violence, both physical and verbal, sometimes with consummate authority (like in Your Body Language Is Not India! or Where I Am Snubbed at a Cocktail Party by a Bharatanatyam Dancer). Often, that inflicted by women on women, a reminder that patriarchy is perpetuated in many insidious ways. It is, in this era of body-shaming, image-shaming and cultural wars waged, especially on social media around authenticity, particularly telling. How did you begin to juxtapose these visible and invisible assaults, one so often delivered by kith?

TD: It comes back to connection, again. It's hard to pinpoint triggers in poems. Of course, the rape of Jyoti Singh was a big trigger, a shift in national consciousness, but then the stories kept coming, the violence, the brutality, three sisters under the age of 11 raped and murdered and found at the bottom of a well. And on and on. Incessant. How do you write about violence without perpetuating it? What do you do with it? In the poem, Meeting Elizabeth Bishop in Madras, I'm thinking of the pain awaiting my teeth, of what it might be like to encounter Bishop there, of her poem, In The Waiting Room, and her contention that pain connects us. A greater violence would be a disconnect. To not feel someone else's suffering. And this is where poetry enters, and dance and film. I remember listening to Wim Wenders describing how he came to make Pina. He'd been dragged to a Pina Bausch performance by his girlfriend in Venice. He said he experienced physical cramps while watching the dancers, and then tears, unrestrained tears. "Pina showed me in 20 minutes more about men and women without words than what the entire history of film has been able to do," he said. I think about that while negotiating the world. How we receive barbs. How we may transform them.

KN: And then Wim Wenders went and made one of the most affecting, memorable documentaries about dance: his Pina was one the very few times I found 3-D to be an organic, integral component of the story. It made the dancing bodies so tangible, so fragile and yet powerful. So, the transformative capacity of art that you speak of is a thing of great potency— and contagion.

And that capacity permeates Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods, I find, that it abounds with life, an enduring fidelity and love that outweighs all the transience, 'that breath outpaces/ any sadness/ of tongue' as you say in A Fable for the 21st Century. It cherishes what we do have, amidst the decay and decrepitude, most flagrantly so in Love in the Time of Autolysis. Could you tell me something more about this poem, it fascinates me with its precise, unwavering post mortem and quiet passion

TD: I was reading an article about what happens to the body, actually, physically, after death. If a body is allowed to just lie there. It basically becomes a farm. There's this profusion of growth. The body gets colonised by these microbes, and there's so much movement, which was so against the idea of what I thought death was, which is stillness, and ending. And if you think about the fact that all humans are made of dead stars—the carbon, nitrogen and oxygen in our bodies was created billions of years ago, that really began to interchange the idea of life and death for me. It's such an incredibly powerful concept of time, which has nothing to do with linearity. We are a part of that, and so this is a love poem, slightly morbid, perhaps, but I really don't see it as so. Because I think love is also like that starstuff, stardust. Always powerfully in play. And when I say, 'the sky will be/ here soon to adorn herself with you./ She is jealous of our history, of our/ afternoons of whispered Ungaretti,' I'm pushing for that relation between human and the cosmos. That journey out and in. We may feel incredibly small in our lives, but we are connected to the universe. And the houses of love we make in our time here are worth singing about.

KN: Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods is richly inventive with form. There are sestinas, a canzone, you've also doffed your hat at Gwendolyn Brook and John Berger with Golden Shovels that incorporate lines from their poems; there are rhyming couplets and more. Do you have a preferred form, and are there forms you're drawn to but haven't attempted yet?

TD: Sestinas are what I love, and I've had a few in every collection. Sonnets are probably what I find hardest to do. But the golden shovel form you were talking about, invented by Terrance Hayes, is a really a wonderful way to pay homage. To weave the words of one poet, and to make another poem from those words, seems to be a perfect metaphor for poetry itself: it begets and begets.

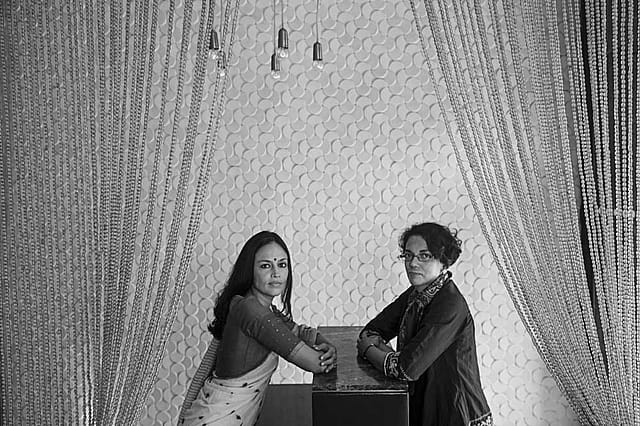

(Tishani Doshi is a poet, novelist and dancer who lives by the sea close to Chennai. Karthika Naïr is a Paris-based poet, dance producer and curator. Doshi has just published a book of poetry and it becomes an occasion for the two to discuss mortality, the female body and finding the lion in the wardrobe)