Tinker a Tale

Several years ago, a man on a motorbike pulled up beside me at a stoplight. He and his passenger had a ladder with several cans of paint affixed to it resting over their shoulders. The man riding pillion had a toolbox clutched in his arms. It occurred to me that we on the Subcontinent have a unique knack for solving problems even when the resources available to us are limited. We reassemble objects in occasionally outlandish configurations to come up with things that are new and useful. From the teenager using a bowl as an amplifier to the auntie who has turned a water bottle into a lantern using just her phone flashlight, our lives abound with examples of every day ingenuity. To my mind, these palimpsests we see all around us are at the very heart of steampunk, a genre defined by its combination of modern technology and anachronistic settings, one entwined inextricably with the now somewhat archaic art of ‘tinkering’.

What has come to be referred to as ‘steampunk’ is commonly thought to have its origins in the work of Jules Verne, HG Wells and other mid-to-late 19th century ‘scientific fiction’ authors. Verne’s submarine-bound Captain Nemo and Wells’ epoch-leaping Time Traveller embody the archetype of the eccentric genius whose explorations transcend the bounds of human imagination. Looking back still further, we find that Wells’ and Verne’s solitary virtuosos owe a great deal to Edgar Allen Poe’s brilliant misfits, from C Auguste Dupin, who unravels mysteries through the process of ‘ratiocination’, to Hans Pfaall, whose balloon flight to the moon is chronicled in exacting scientific detail.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Literature tends to reflect the concerns of the time and the works that would come to form the basis of the steampunk movement were no exception, fanciful as they were. The novels of Wells, Verne and others clearly reflect the prevailing fascination with expanding technology and the exotic new lands imperialism had begun to demystify. With the advent of the World Wars, however, global focus shifted. Heroes like Superman and Captain America, who were quite literally encased in iterations of national flags, replaced the more genteel Phileas Foggs and C Auguste Dupins. As we crept from the Atomic Age to the Space Age, these godlike champions battled forces of inconceivable evil—often across the vast backdrop of outer space. After the somewhat less colourful reality of the 1969 moon landing, intergalactic supermen began to fall out of fashion, making way for the return of the dandy-inventors of Victoriana.

Having been raised on a steady diet of classic novels during the period in which the Subcontinent was poised on the brink of technological modernity, the idiosyncratic combinations of old and new struck a chord with me in a way that superhero epics, with their bulletproof heroes blessed with boundless resources, never did. I inhabited a world where modems were being set up next to phonographs that were very much still in use. When I first read The Golden Compass, it seemed only natural that advanced scientific procedures like ‘soul-splicing’ could be performed by characters who arrived at their laboratories by dirigible, abundantly possible that, as in The City of Lost Children, a cyborg cult could steal children’s dreams in a rickety, riverside city with distinctly Belle Époque flavour. These were science fiction worlds to which I could relate and I immediately adored them. It was years and years before I first heard the word ‘steampunk’—a categorisation that has been applied perhaps retrospectively to such works.

The term ‘steampunk’ was coined by KW Jeter, author of Morlock Night, in 1987 to describe a genre of retro futuristic speculative fiction in which steam-based technologies have carried over into modern times. William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s The Difference Engine is considered one of the seminal works of the genre, having established many of the archetypes that came to define it. The Difference Engine imagines a world in which Victorian mathematician Charles Babbage succeeded in the creation of his Analytical Engine and the Computer Age arrived a century early. Set in 19th century London, it put in place some of the early conventions of the genre, from the obscure steam-powered technologies that never really took off in our particular timeline to the re-imagined global history. The book was highly acclaimed, winning both the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the British Science Fiction Award, while unwittingly establishing a new subgenre of science fiction.

The next two decades saw a profusion of works loosely associated with steampunk, from Philip Pullman’s retelling of Paradise Lost in the His Dark Materials trilogy, to painter James Gurney’s lushly illustrated Dinotopia series, to the Dresden Dolls’ ‘Brechtian punk cabaret’. Even so, the genre remains difficult to define in that many of the artists and writers whose works are considered foundational seem to want nothing to do with it. China Miéville, whose Perdido Street Station is considered paradigmatic, rather diplomatically stated that he knows very little about the genre and William Gibson called it ‘the least angry quasi-bohemian manifestation I’ve ever seen’. To my mind, the widespread discomfort with being associated with steampunk lies in its trappings, which are decidedly costume-y. Serious authors exploring complex social and philosophical issues through the lens of science fiction are hesitant to align themselves with an increasingly commercialised genre that also encompasses a subset of individuals who enjoy dressing up in goggles and corsets and drinking complicated cocktails in barrooms with brass fittings. There is nothing less literary, it seems, than being affiliated with the contents of an Etsy shop.

Google ‘steampunk’ and you will see a wide array of monumental moustaches, brown leather garments and gear-adorned devices of dubious practicality. Ridiculous, right? Now Google science fiction: what do you see but a bunch of cool-hued pastels, phallic symbols and fan art that looks like it was created expressly for the purpose of being printed on free t-shirts? Now consider the fact that some of the most lauded books and movies of the past decade technically fall under the umbrella of science fiction, from Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West to Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. At times like these, it is worth remembering that Kurt Vonnegut was widely dismissed as a ‘genre writer’ until the publication of Slaughterhouse-Five. A great many things are idiotic trends until they have endured long enough to become canon. Steampunk, I believe, is one of them.

If fantastical fictions tend to examine the anxieties of our times, steampunk’s exploration of how we relate to machinery seems particularly relevant. China Miéville’s cyborgs are hardly outlandish in an era when we can’t bear to be without our phones for more than five minutes. The idea that we will someday soon have technology implanted in our bodies is coming to seem less like an especially horrifying episode of Black Mirror and more like an imminent reality. With the world around us changing so quickly, science fiction provides a forum through which we can investigate the implications of these changes. The repurposing, reusing and recycling characteristic of steampunk seem more like practicality than nostalgia, the emphasis on modification not merely aesthetic, but instead a reaction against the generic sterility of mass-production.

The Catastrophone Orchestra and Arts Collective defends steampunk against charges of triviality, writing: ‘Too much of what passes as steampunk denies the punk, in all of its guises. Punk—the fuse used for lighting canons. Punk—the downtrodden and dirty. Punk—the aggressive, do-it-yourself ethic. We stand on the shaky shoulders of opium-addicts, aesthete dandies, inventors of perpetual motion machines, mutineers, hucksters, gamblers, explorers, madmen and bluestockings. We laugh at experts and consult moth-eaten tomes of forgotten possibilities. We sneer at utopias while awaiting the new ruins to reveal themselves. We are a community of mechanical magicians enchanted by the real world and beholden to the mystery of possibility. We do not have the luxury of niceties or the possibility of politeness; we are rebuilding yesterday to ensure our tomorrow. Our corsets are stitched with safety pins and our top hats hide vicious mohawks. We are fashion’s jackals running wild in the tailor shop.’

Though it espouses precisely the opposite philosophy, this statement owes more tonally to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism than it does to the clockwork-adorned iterations of steampunk that seem to so aggravate writers and artists with their Disney-fied simplicity. What it leaves me wondering is, why can’t it be both? Why can’t it be the downtrodden and dirty but also the dilettantes in their elaborate dresses? Is it necessary for art, always, to be serious in all its forms?

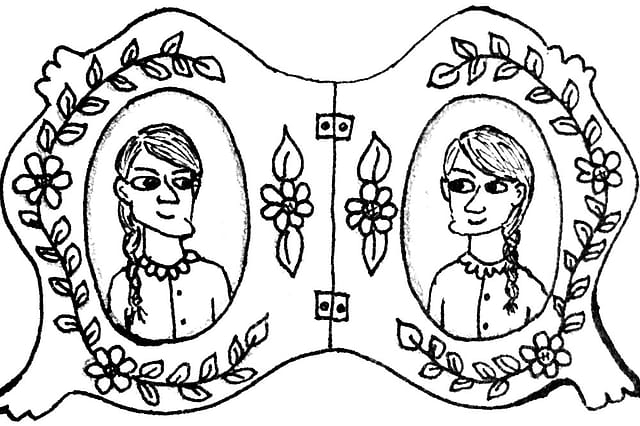

When Arapaie Black, the illustrator of the book, and I first came up with the idea of The Flight of the Arconaut, we thought a great deal about what we wanted our post-apocalyptic world to look like. Atlantis, we decided, would be an artificial island located in the South Philippine Sea. We wanted our dystopia to be tropical, monsoonal rather than foggy, vibrantly coloured rather than grey. We wanted to interpose the worlds we knew (Japan in her case; Pakistan in mine) over our science fiction universe. We wanted to know what would happen to people like us when the world ended. Although we initially shied away from steampunk tropes, Nyx’s world is in some ways inherently steampunk. Having been built upon the ruins of our world, there are traces of our technologies, customs and cultures. Atlantean civilisation has evolved out of the scraps of our existence. It is pieced together out of what was left behind. And so, in time, we embraced the conventions of steampunk in all their glory. I know Black enjoyed drawing all the goggles and gears and clockwork devices. I certainly enjoyed writing the eccentric adventurers and madcap exploits. Perhaps part of the appeal is how the genre harkens back to a time when we were more active participants in our own existences. There is no need for ratiocination now. We Google. There is no need to cobble together devices out of what we find lying about. We order off Amazon. And perhaps this is why we need prodigious flights of fancy more than ever in our imaginary worlds.