The Vernacular Vibe

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE can best be defined as indigenous architecture of a people or locale, based on social and environmental needs and preferences, and made from locally available building material with available skills. It would include not only individual structures but collective areas like the pols of Ahmedabad and other areas of Gujarat or the mohallas of cities of northern India— complete facilities for the inhabitants, which could be group or caste specific. The concentric temple towns of the south are other such clusters. Within a repetitive format of a community template though, there was sufficient room for individual expression.

Environmental extremes in India also necessitate diverse vernacular forms to adapt to the climate and season excesses—from dry deserts to a long, humid, coastline, the lofty and heavily forested Himalayas and other lesser mountain ranges (Aravalli, Nilgiri, Sayadhari), and the Deccan plateau—with climates varying from temperate to tropical and with rainfall varying from almost nil to heavy. Diverse occupations also require corresponding local designs of houses according to professional needs. Local vernacular construction of a few decades ago, was not an isolated development but a part of the craft-guilds’ output, which included other crafts in the village community which catered to all the needs of society.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Urban and village definitions of settlements became contiguous in cities like Delhi and even in the days of Aurangzeb the traveller Francois Bernier wrote of Shahjahanbad as a collection of many villages. There is also, thus, a close physical link between the two—the old and the new forms, both often existing next to each other.

Vernacular architecture is essentially ‘architecture without architects’, as there were no formal architects earlier but mainly artisan guilds and master masons. Not much is known of the master builders of vernacular as well as monumental architecture. Vernacular buildings had sutradhars who were not architects in the modern sense of the word but master masons. Some monuments, however, do record and even illustrate the builders of monuments, like the victory tower in Chittorgarh, which includes a sculpture of the master designer and his family and assistants. Overall vernacular architecture was based on vastu and Shilpa shastras. Unlike as in residential architecture, detailed plans were made for larger monuments, the likes of which can still be seen carved on stones near the Bhojpur temple, Madhya Pradesh.

It is only natural that builders in Bikaner and Jaisalmer would use stone since it is abundant there, while in Bengal, lacking stone, bamboo and bricks were used. The Gangetic plains had to use mud (at times combined with wattle), clay and rubble or bricks. Timber was the natural material for the Himalayas and coconut palms in southern India. Laterite is the preferred material in regions of the south where it is abundantly available. The more well-off would, naturally, try to bring in outside inputs to set them apart from the rest. Climatic requirements, too, would be different for different regions of India—desert and pasture-lands of Kachchh, tropical and temperate regions, the Himalayan and other ranges, the Deccan plateau and the southern states. In the extreme heat of northern India, inverted pots were put not only on roofs but even under intermediate floors, for heat insulation.

Changes in the environment and needs of the inhabitants would also provide impetus for structural change of residences. External influences would also modify the vernacular styles like the advent of colonial architecture by the British and their neglect of traditional building forms. Many years down colonial rule, the British did realize that they, perhaps, could and should have encouraged the use of vernacular skills and designs. A group was set up to explore what skills remained in the then Indian building industry and decorative methods that could still be used, but by then it was too late.

Vernacular architecture also evolves and adapts continuously. The term vernacular is relative and not absolute. Thus, the modern flats and apartments of today might be the vernacular a century from now. Similarly, in a metropolitan city cement might be more readily available locally than bamboo or earth. Unfortunately, the term vernacular is also associated with something primitive and backward.

Looked at from a view of sustainability rather than just nostalgia and historical interest, vernacular design is evoking interest for sustainable habitats, as formally ratified by Agenda 21 of the 1992 Earth Summit at Rio De Janeiro. The international follow-up body for this was the Commission on Sustainable Development, setup in 1992 by the UN. These concepts of sustainable settlements were further stressed by the UN conference on Human Settlements at the world summit on sustainable development that took place in Johannesburg in1996.

With no need now for natural climate adjustment in summer with the use of air-conditioners, climate has become less of an issue in house design and construction. It is a different matter that it puts a greater demand on non-renewable energy resources and pollution from coal-based thermal plants.

Though smaller in scale than the much larger monumental buildings, vernacular residential structures share some common building elements with them, influenced by inputs from conquering dynasties and colonial rulers. The decorative aspects also draw on the craft traditions of the area subject, of course, to the community — whether Hindu or Islamic, with the latter’s ban on depiction of anthropomorphic forms. On the other hand, monumental architecture also borrowed elements from vernacular structures like the bamboo eaves of the humble bangla hut. The lifetime of the residential structures ranged from huts that served its purpose for a cycle of seasons only before they were flattened by the elements to more permanent structures like havelis and mansions.

It is not necessary to simply preserve and imitate vernacular buildings in toto—which might be impractical at present— but to understand the processes involved in their construction. Many architects and enthusiasts have successfully imported vernacular elements in their designs which are well suited for current sustainable practices.

Though all the styles of vernacular structures were eminent with features that make them attractive even today, not all vernacular forms are great or relevant now—like the Shekhawati murals in the courtyard houses on every square inch of houses, or the stepwells which, over a period of time, became sources of guineaworm and other diseases.

There has been a renewed interest in vernacular and traditional structures in the world and architects who have made a reputation in using vernacular forms and features include Hasan Fathy, Geoffery Bawa, Louis Kahn and others, including Laurie Baker in India. Worldwide interest in vernacular building traditions has also resulted in research and resources relating to such structures, including the barn of North America and other notable vernacular residential architecture, some of which are UNESCO world heritage sites like those of the Asante of Ghana, those in the M’zab valley of Algeria and the Sukur cultural landscape, Nigeria. Old city centres like Naples, Shibam in Yemen certainly have a community feeling that modern buildings lack.

Not many ancient remains of complete houses have been found preserved in great detail like at Pompeii. Some structures have been identified in excavations of the Indus Valley civilization, which is the start of the period of the use of sun-dried and fired bricks. Even in monumental architecture stone-work started in Ashoka’s period and prior to that both domestic and monumental architecture must have been mainly wood. This is proved by the depiction of wooded beams and rafters in some rock-cut caves in Ajanta, in stone itself. The Karli, Bhaja and Kondane caves still retain their original wooden ribs that were put there for no structural reason but possibly only because of the heavy influence of wood as a building material in those times in non-cave structures.

Like the last wave of modern palaces, architecture prospered when there were no wars and under the complete rule of the British, especially after the 1857 struggle for freedom from colonial rule and till the upheavals of Partition in 1947. Under British rule, though extraneous inputs started coming, the wealthy could build more lavish residences than they could under native rulers as now there was no problem about attracting undue attention from the ruler. The British even standardized the size of bricks as 9x4.5x3 inches. Prior to that thin nanak-shahi bricks were used in the country and locally made clay drain-pipes.

Mohenjodaro and Harappa used gypsum plaster and use of lime came later, and its use spread particularly after Muslims came to India. Later on, around the eighteenth century, lime stucco-work became popular amongst the wealthy wherein it was mixed with marble powder and given a smooth polish. Where available, timber and timber bonded structures were made, the wood usually being deodar in the hills and teak in the plains like Gujarat, or even coconut trees in Kerala. In between, in the foothills of northern India, saal or Shorea robusta was a good general purpose timber. In the north-east bamboo was ideal material to use for structures and when split, its parts could be woven into a screen. Thatch roofing was generally used for huts. Relatively newer materials were glass for windows and corrugated iron. In the absence of availability of glass earlier, shells were put in a cluster in windows in the coastal areas and the buildings of Goa still retain them where they serve the purpose of present-day frosted glass in a natural manner.

The main vernacular form was the courtyard house, which was a remarkable form of residential architecture. The courtyard was this style’s quintessence and its relevance to the home was apparent as well as subtle. It was the structure’s core. The courtyard ordered other spaces by context in an abode where space was not rigidly fixed but could be adaptable depending on the time of day, season and exigency. It obliquely controlled the environment inside and served the needs of its inhabitants. Its moods changed with varying degrees of light and shade, and with them the ambience of the abode. Centrally located, it imprinted the domain of the dwelling like a visual anchor. Around this courtyard space the rest of the structure seamlessly coalesced by the play of epistyles and gallery spaces. It was the spatial, social and environment control centre of the home.

This form of architecture met with the requirements of the traditional joint family system as well as the climate. The courtyard functioned as a convective thermostat and gave protection from extremes of weather. A dust storm could pass overhead with little effect on the inmates. The courtyard moderated the extreme effects of the hot summers and freezing winters of the Indian sub-continent, and averaged out the large diurnal temperature differences. It varied from being a narrow opening to a large peristyle one in the interior zone of the house, with perhaps another or more near the entrance and the rear section. The total number of courtyards in one residence could sometimes be five to six.

Visitors stopped at the outer courtyard where the baithak, sitting place, usually was. Beyond this was the sequestered zenana, women’s area, around the inner courtyard. In urban areas where space is limited and only one small courtyard could be constructed the female quarters were moved up vertically to the upper floor. The courtyards came alive during extended marriage celebrations and festivals like Holi and Diwali. In a courtyard’s time space there would also be the admixture of intrigue, flirtation and scandal. With the fading out of the institution of the joint family, pressure on land and mechanical means of temperature regulation, this form of residential architecture is naturally falling into disuse.

The courtyard house form in India was not based on blind conformity and there was tremendous innovation in the design of such homes, known variously in different regions—haveli in northern India where they were prominent, wada in Maharashtra, nalukettu in Kerala, rajbari in Bengal and deori in Hyderabad. All had regional variations in design and craft techniques, using stone, wood, bricks and mortar. The expression haveli is derived from the old Arabic word haola, meaning partition, and hence the earlier Mughal use of this word to denote a province. In modern Arabic the word havaleh means encircling, confirming the linkage. Even similar elements of design have the same nomenclature, like the mashrabiyya (cantilevered screened balcony) of the Arab courtyard house and the Gujarati haveli.

Courtyard house architecture reflected the style and culture of its time. It was indicative of the owner’s self-image and aspirations, with a distillation of historical influences. It manifested itself in degrees, varying from solidity to extreme ornamentation.

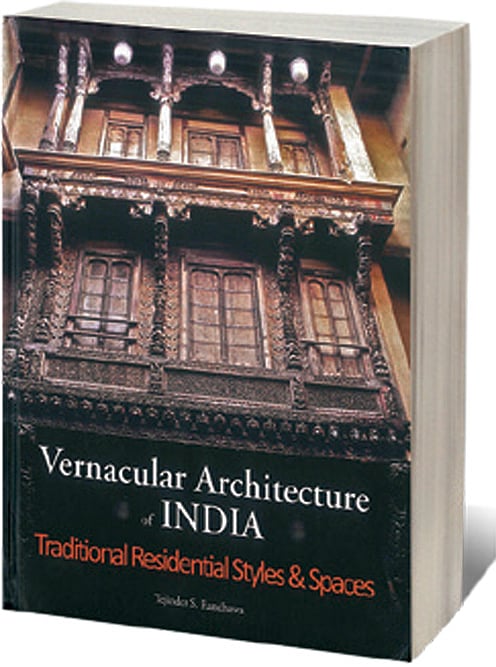

(This is an edited excerpt from Vernacular Architecture of India:

Traditional Residential Styles & Spaces by Tejinder S Randhawa)