The Science of Believing

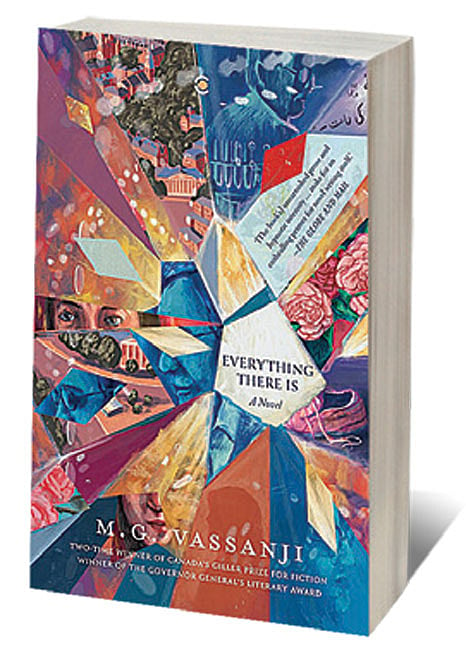

MOST PEOPLE WONDER what Nobel Prize winners are like in real life. One stereotype is that they are earnest and unassuming, wrapped up in their profession. Another stereotype dictates that they are arrogant in their brilliance, impatient and entitled. Nurul Islam, in Moyez G Vassanji’s latest and tenth novel Everything There Is (Context; 312 pages; ₹699), although not very humble, has most of these qualities. It is a compelling and plausible portrayal, based in part on the real-life Pakistani theoretical physicist Abdus Salam who won the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics. Nurul’s motives for winning the prize are clear when he muses one shouldn’t “think about prizes; the best prize was the opportunity to do what he loved, but the Nobel was one gift he could give to his mother and father, to his country.” Like Salam, Nurul is an internationally renowned physicist and professor at Imperial College, London in the 1960s and ’70s. Nurul also was a maths prodigy in a Pakistani village school who got a scholarship to Cambridge, and was a rising star in the field. Additionally, Salam and Nurul, strangely enough for men of science, are deeply religious. It is this contradiction that inspired Vassanji, the award-winning Canadian writer, to make this the subject of his new novel.

“It was the conundrum of a person working at the highest level of theoretical science, where most of your contemporaries at that level believe there’s no need for a god,” explains Vassanji, 74, to Open. Vassanji’s conversation is measured, and his replies are to the point. When he speaks of Salam, he shows his deep interest in him, as Salam defies the expectation that leading scientists should be agnostics. “This is what intrigued me, where you are at that threshold of knowledge, when there’s really no need for a god. Salam didn’t just believe; he worshipped. That was the other extreme.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

When the book begins, Nurul is at the top of his profession, and is secure in his faith. He is close to achieving a unification of the forces along with the American scientist Abe Rosenfeld. He is a happily married family man until he falls in love with Hilary Chase, a young graduate student in the US. Even then, Nurul’s luck seems to hold as his wife Sakina, after her initial shock, gives her blessing to allow him to marry Hilary bigamously, and his family and well-wishers gradually accept the situation. This is when a combination of events causes Nurul’s credibility in the academic world to be challenged, and lead him to have a crisis of faith.

I ask Vassanji, who is passing through Delhi, and who has a PhD in nuclear physics if he is agnostic. He replies, “It’s not necessary for me to believe in a god. If there is one, fine. It has no impact on me.” He adds he never was at Salam’s level. “Nurul and Salam were at the highest levels of their field and were respected. My nuclear physics was theoretical.”

Even so, as Vassanji has a BSc from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania, he knows the culture of physics departments in the ’70s, and is able to recreate that atmosphere in his book. Much of the novel takes place in the fast-paced scientific world, and inevitably discusses a great deal of physics. Yet, it avoids dense theoretical language, and it is explained sufficiently in layman terms. It conveys the duality of global academic circles; simultaneously small and sheltered, yet exclusive and competitive. Vassanji comments on the intensity of these decades and of spotting renowned scientists of that time. “In those days all these great physicists used to pass by in MIT like [Werner] Heisenberg. It was a very exciting time for a student.”

Along with the cut-throat nature of academics, the co-existence of science and religion, Vassanji also writes on migration, exile, and identity. These are themes prevalent also in his earlier works, such as The In-Between World of Vikram Lall (2003) and No New Land (1991). This time, Vassanji comments on the nature of religious intolerance as well, which he had previously explored in his last novel A Delhi Obsession (2019). While that book dealt with the bigotry of extremist Hindus against the background of what they see as ‘Love Jihad’, in his new book Nurul is targeted by Muslim fundamentalists in Pakistan. Vassanji affirms that he wrote these two novels, partly in response to a shift he observed in political trends and extreme reactions. “I was particularly angry when I was writing A Delhi Obsession. There was no message in the novel, I was just responding to the madness I saw. This background where people not only judge other people but incite violence against them.” This background is also present in Everything There Is, where Nurul is attacked by fundamentalists because he promotes his views on what physics means to him, and how that did not impact his faith. He feels he can use his academic achievements to help his “small beleaguered Shirazi sect that always had to justify itself to the Islamic world.”

In this case, Nurul differs from Salam as Salam was an Ahmadiyya and was persecuted for his religion by the Pakistani government. Nurul’s religion is incidental to the plot. He was targeted more because of his belief that his religion and physics could coexist. Vassanji explains this change, “If you take a real community, you have to know the whole background and history. That wasn’t important for my novel.” The idea of writing a character based on Salam had been on his mind for over seven years. As a Nobel Prize winner who is not celebrated in his country today as his community was declared heretics and who allegedly supported Pakistan’s nuclear programme, Salam’s story is unforgettable. Vassanji says, “Ahmaddiyas are scared. They can’t even call themselves Muslims without going to jail. When I was researching Salam, I read about his grave, which keeps being desecrated, and someone from his community washes it, and some fundamentalist again desecrates it.” However, Vassanji believes that if Salam had indeed supported the nuclear programme, the government would have protected the Ahmadiyya community. He poses the question, “He was important, a major figure, and if it was known that a person of that eminence was supporting the nuclear programme, how could they have declared him a heretic?”

In contrast, Vassanji decided to go the opposite way with Nurul, who refuses to support the Pakistani nuclear programme. His decision is traced back to his experiences with Partition. Although he and his family were largely unscathed, he witnessed the damage and violence done to several other families, which profoundly affects him. The military is antagonised by his refusal to be involved in the project and remove their protective hand from him, allowing him to be attacked on all fronts.

Defeat seems inescapable for Nurul and he is simultaneously targeted by a coincidental combination of forces. First, ignorant fundamentalists publish photographs of him and Hilary during the early days of their relationship. Meanwhile, in a trajectory echoing Salam’s path, a critic in England constantly claims Nurul is a fraud, and a senior scientist in Holland is dismissive of him, decreasing his standing in the scientific field. At one point in the novel, Hilary wonders about Nurul’s downfall. “Perhaps it all started with me. The evil American second wife.” However, it is clear that Hilary was just a means for his countrymen to target him, as they were determined to get him one way or another.

Considering the role Pakistani military and fundamentalists play in his ruin, it is remarkable that Nurul does not define himself as a Pakistani or Muslim scientist, but just as a scientist. This choice of identity has not only been explored by Vassanji in his works but has been experienced by him. Born in Kenya to Indian immigrants, raised in Dar es Salaam, and now settled in Toronto for decades, Vassanji is assured in his definition of identity. “Identity is just ticking off boxes according to government forms, but belonging is where you step down from a bus or plane or wherever, you breathe the air, and say, ‘yes, this is it’. For me that is when I go back to Africa, or when I come here to Delhi. In Dar es Salaam and Nairobi, and sometimes in Toronto, it’s a sense of familiarity about belonging, that no one can take away from you. Only you decide where you belong, not some government official.”

Identity is a central theme in Everything There Is, along with religion, responsibility, and choices, making the book much more than a discussion of theoretical physics. It is part biography and part novel. Even though most of the action takes place in only the last 100 pages, it is still a moving picture of the tragedy of a brilliant, once fortunate man.