The Many Tongues of the Forest

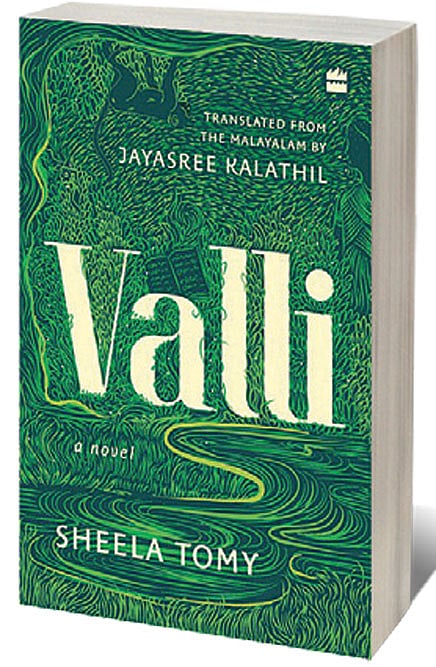

IN HER DEBUT novel, Valli (HarperCollins, 420 pages; ₹699), award-winning Malayalam short story writer and screenwriter Sheela Tomy captures the essence of the dying yet resilient forests in India, along with how it is nurturing yet brutal at the same time.

Valli was originally published in Malayalam in 2020, and won the Cherukad Award for Malayalam Literature. It has recently been translated into English by the author Jayasree Kalathil. The book is set in the forests of the migrant village Kalluvayal in Wayanad, located in the Western Ghats of northern Kerala. It follows the lives of teachers Thommichan and Sara and their daughter Susan. Valli opens in the 1970s, when Sara and Thommichan come to Kalluvayal as newlyweds and teachers at the government school, and ends with the 2018 floods in Kerala. Side by side, it is also the story of the forest and its transformation over five decades.

Valli is set against the backdrop of true events in Kerala. The night in February 1970 when Sara and Thommichan arrive in Kalluvayal, real-life figure Comrade Varghese is killed in a police encounter. Naxal activity in Wayanad hums in the background, but Valli primarily focuses on Sara and Thommichan’s family and their friendship with a landowner’s son Peter, his wife Lucy, their love for their forest home and their efforts to help the Adivasis, the Paniyars, who live in harmony with the forest and yet are bound to the system of ‘vallipani’. Speaking from Doha, where she is based, Tomy tells Open, “Vallipani was the contract labour system in Wayanad where the workers and their families were forced to work for the jenmi [landowning class] for a whole year for a certain measure of rice—also called valli.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

This system contributed to the rise of the Naxal movement in Wayanad. Comrade Varghese had attempted to abolish the vallipani system and establish fair wages but he was killed. After Varghese’s death, Thommichan, his fellow teacher and activist Padmanabhan, and Peter try to speak up for the rights of the Adivasis, but their idealism is pitted against powerful interests. The reality of the seemingly peaceful village life is brought into focus, reflecting the dual nature of the forest—both enchanting and deadly. Tranquillity is constantly juxtaposed with violence. The jenmis appropriate all the land, and the police are their willing agents.

Valli’s organic storytelling reflects the nature of Kalluvayal’s forest, fluid, dense and intricate. The novel itself, like the forest, defies the standard structure of a neat linear narrative. Valli is told through a diary Susan—Sara and Thommichan’s daughter—leaves for her daughter Tessa. It encompasses 50 years and four generations, and uses letters, emails, diary entries, newspaper reports, Bible quotations, poems, and film and folk songs. The newspaper report fragments and multiple ‘sources’ give ballast to the plot, and the events that happen— the disappearance of tribals, Naxal attacks, and elephants trampling crops. The poems and folk songs, the Biblical references bring the distinct Wayanad culture alive. Tomy explains, “The Bible and the Church played a significant role in the lives of the migrant communities of that time. Therefore it appears in the story as well.”

The book seamlessly switches perspectives, jumping from Thommichan’s time to his daughter Susan’s and his granddaughter Tessa’s. This format is effective: the framework of Susan’s diary gives the story an immediacy; the multiple perspectives allow readers to understand other viewpoints and the complexity of their interconnections. It makes for an intense, compelling read, with convincing characters who have all-too plausible storylines.

However memorable all these characters are— jealous and grasping landowners, eager teachers and activists—the forest towers above them all, and is itself a major protagonist, as are the Adivasis, who defend it. The forest emerges as an entity with its own complex emotions and secrets, enduring plunder from landowners and corporates for decades. Tomy’s view of the forest as a protagonist is part of a trend which sees nature as a character in its own right; for example Amitav Ghosh’s recent book The Living Mountain.

If Tomy is unsparing in her depiction of the forest’s ill-treatment and the dangers that arise from it, she is lavish in detailing its wonders. From the beginning, the newlyweds Thommichan and Sara are enchanted with the forest and its river Kabani. In Tomy’s redolent, elaborate prose: “Lush ferns grew at the riverbanks around black-hued rocks covered in tiny blue parakkuriniji flowers. Minnows flitted in the rock pools and egrets meditated in the knee-deep water.” Their daughter Susan inherits this love for the forest, and carries it with her to her urban life as an architect. Her daughter Tessa, training in robotics, comes to love it as well, and like her family, empathises with the struggles of the Adivasis.

Tomy had visited Adivasi settlements near her home in Wayanad. “Some of them are my friends. They were very welcoming and happy to share their past, their thoughts, songs and customs,” she recounts. Their experiences are of exploitation and hardship. As Tomy writes in the author’s note, “There is a story to be told…, and that is the bitter story of those who were subjugated and discriminated against.”

The novel’s very title conveys the complexity of the Malayalam tongue. The word ‘Valli’ has several meanings. Valli is Earth; it is a novel for earth and nature, the author explains. “Valli is the climber plants found abundantly in the forest of Kalluvayal. Valli is wages. Finally, valli is a woman; this is a story of women and nature.” All these meanings address the themes at the heart of the novel.

The ‘valli’ women in the novel continuously struggle, and are repeatedly crushed if not actually brutalised, like Kali the Adivasi girl. They suffer in other ways. Susan is constantly torn between her love for the forest and her life in the city. The indomitable Lucy, who Peter calls ‘the queen of the forest’, gets increasingly weighed down by her losses, as does her mother-in-law Annamakutty. Some, like Lucy’s sister-in-law Isabella, survive to give hope to the community. The women in the story, like the forest, ultimately refuse to be exploited.

Susan’s path mirrors the author’s own. Tomy herself was born in a Christian migrant village in Wayanad. She writes, “My home was by the bank of the Kabani river, and across the fields were dense forests.” She grew up amidst paddy fields, harvest festivals and listening to the trumpeting of wild elephants and to old folktales of the forest. Tomy, like Susan, Thommichan, and Valli’s other protagonists, also witnessed the gradual diminishing of the forests and paddy fields due to encroachment. This, says Tomy, resulted in farmers struggling to survive and Adivasis who had once fought for valli (wages), fighting for valli (earth). Tomy’s father, like Susan’s, had been a schoolteacher, but from a family of farmers. He had urged Tomy to write about her land and people. It was many years before she did.

Tomy’s road took her away from her village, and eventually to the Gulf after she was married, where she has lived for the last 19 years. She started her career at the LIC, but she also wrote for various newspapers and journals. Her short story collection Melquiadesinte Pralayapusthakam, (Melquiades’ Book of Floods) was published in 2012. However, like Susan, she never quite forgot the forest.

“I badly missed my land, the forest, river, mist, rain and even the cool breeze of Wayanad,” says Tomy. This sense of exile turned into a novel. The process was long and arduous. “Valli was there in my mind for more than a decade. Understanding the history, politics of the land and labour, flora and fauna, etc. happened simultaneously with the writing. It took three long years.” Tomy also read and researched extensively and listened to the stories of her elders. Her love of her forest home is reflected in her characters’ love for it and in her own continuously vivid, evocative and lyrical prose. As Sara and Thommichan take their first walk in it, “The forest spoke to them… Giant mountain squirrels chattered in the trees, and jungle fowl and hare skittered in the undergrowth. A hundred different birdsongs, a soothing coolness, fragrances”. Tomy’s words describe a place so idyllic it almost seems idealised. Her words are clearly born of nostalgia.

Apart from the writing of the novel itself, the translation process was of equal significance. Valli is testament to Kalathil’s skill as a translator and deservedly is in the reckoning for awards, including the long list for JCB Prize for Literature. Tomy emphasises the significance of translations, including regional ones. “Translations pave way to new horizons,” she says. Their importance has increased exponentially in India since Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand won the International Booker prize this year.Beyond writing the story of her old home, Tomy had always hoped it would reach a wider audience. “When I wrote Valli I was dreaming that one day the world would read the stories that only my forest village could tell.” It was therefore serendipitous when shortly after publication, during the Covid lockdown Jayasree Kalathil contacted her and asked for permission to translate the book. Kalathil had earlier shared the JCB Prize for Literature in 2020 with S Hareesh for her translation of his novel Moustache. Despite Tomy being based in Doha, and Kalathil in India, the process of translation was stimulating. “We were continuously in touch through chats and calls. It’s amazing that she was checking the facts, referring to books and reading the Bible to reflect my quotes from the Bible correctly. She did justice to the Paniya language which has no script, keeping the essence.” She emphasises that Kalathil understood the text completely and brought out the book’s “poetry and politics” adding, “Valli in English, is a book written by Jayasree and me together.”

It is hard to place Valli in one category; as eco-fiction, or political and social commentary of a people and their struggle for their home and rights, or the story of a family. Valli may seems like a familiar formula—with recognisable characters, and its themes of exploitation and suffering—but its complex non-linear structure, its exploration of the diverse nature of languages, and the fact that the Kalluvayal forest is a major character gives this story a language of its own.