The Man and the Ideal

IN SANSKRIT, THE word ‘maryada’ has several meanings. The etymological root of the word implies something that sets a limit or a boundary. Therefore, in geographical descriptions, texts speak of mountain ranges between regions that are like boundaries. They are known as maryada parvatas. In transactions, you and I may have a contract. That is maryada and violation of maryada will represent a breach of contract. As societies evolved and large numbers of individuals gathered together and interacted, norms evolved on what is proper conduct. Understandably, these norms of good behaviour are often society and context-specific. Nevertheless, these norms are maryada too and anyone who violates these violates maryada and treats ethical norms with dishonour. The word ‘dharma’ can only be translated imperfectly into English, since in different contexts, it means different things. There is moksha dharma, the dharma of emancipation from samsara, the cycle of existence, involving birth, death and rebirth. There is raja dharma, the rules according to which a king should govern, punishing the guilty and protecting the virtuous, ensuring swift dispute resolution. There is dharma that individuals follow, transcending, but not to the exclusion of, the dharma of the four varnas and four ashramas. Conflicts between different notions of dharma are inevitable and depending on the decision taken, an individual reaps the consequences. Karma, a word that again has multiple meanings, is the flip side of dharma.

The Mahabharata is longer than the Ramayana. Not only is it longer, it is much more complicated, encompassing the views of multiple protagonists. In contrast, the Valmiki Ramayana is not only shorter, it is primarily, though not exclusively, a portrayal from Rama’s perspective, which is the reason it is known as Ramayana, Rama’s progress. Perceptions about the Ramayana aren’t always based on Sanskrit versions. There are non-Sanskrit renderings of the Ramayana too, sometimes more popular today than Sanskrit versions. Even within the category of Sanskrit Ramayanas, there are versions of the Ramayana story in Kalidasa (Raghuvamsam) and the Ramopakhyana account in the Mahabharata. Other than Valmiki Ramayana, there are also Adhyatma Ramayana and Yogavasishtha Ramayana. There are few people who know the Ramayana as well as Arshia Sattar. This is particularly true of Valmiki Ramayana. She has done an abridged retelling, a book on ‘Uttara Kanda’, a book on Rama’s conduct and has written the stories in separate books for children. Perhaps one should add that there is a Critical Edition of the Valmiki Ramayana text, published by Baroda Oriental Institute, and most people work with that. Today, the Valmiki Ramayana (and most Ramayanas) has seven kandas or books: ‘Bala Kanda’, ‘Ayodhya Kanda’, ‘Aranya Kanda’, ‘Sundara Kanda’, ‘Kishkindha Kanda’, ‘Yuddha Kanda’ and ‘Uttara Kanda’.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

We don’t precisely know when the Valmiki Ramayana was composed, nor when it reached some degree of finality as a text, with additions and interpolations. Comparing various manuscripts, the Baroda Institute produced the Critical Edition, excising shlokas, especially from ‘Uttara Kanda’. Most people will say ‘Uttara Kanda’ is a later interpolation. Indeed, the language and quality of poetry is often inferior to that in, say, ‘Ayodhya Kanda’. This is also true of ‘Bala Kanda’. But there is nothing to suggest that this division into seven kandas existed from the beginning. That kanda classification also probably occurred later. Hence, logically, there can be older sections in ‘Bala Kanda’ or ‘Uttara Kanda’ and newer sections in ‘Ayodhya Kanda’. Therefore, I feel slightly uncomfortable with statements such as the following; ‘If we work with the well-established assumption that the Bala Kanda is a later addition to the middle books of what we call the Valmiki Ramayana, our first encounter with Dasharatha is in the Ayodhya Kanda’ (page 19). But that is a very minor point and doesn’t alter the substantive arguments of this book.

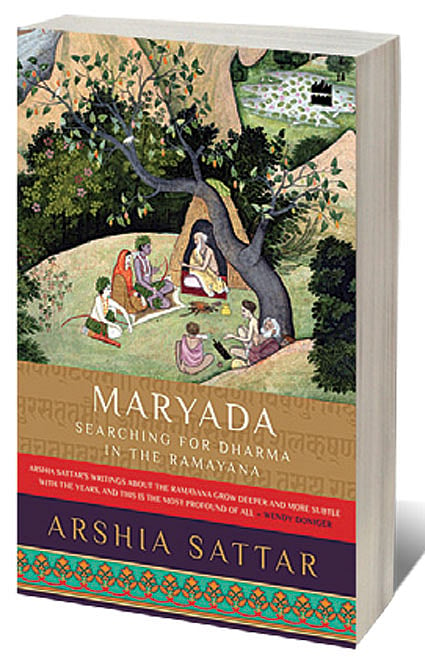

What is this book about? ‘Rather than provide a conclusive definition of dharma in the Ramayana, the essays in this book seek the various boundaries that different ideas of dharma come up against, boundaries beyond which actions become transgressive and deserving of punishment. ‘Maryada’ is a commonly used word for ‘boundary’ in Sanskrit. It also means ‘propriety of conduct’, and with this additional connotation, it holds within itself the idea that the boundary it refers to cannot be crossed without some kind of retributive action. In the context of the Ramayana tradition, the word maryada carries a special weight precisely because the word comes to be used as Rama’s defining virtue. Within the tradition, and especially after the later Ramayanas, Rama becomes known as the ‘maryada purushottama’, the ideal man. In fact, it could well be that the meaning of ‘maryada’ as ‘good conduct’ comes from Rama’s essential association with the concept of propriety itself.’ (page 2). That’s the reason the title of the book is Maryada, with the subtitle of Searching for Dharma in the Ramayana. ‘Searching for Dharma’ would have been too vast and difficult to pin down. ‘Maryada’ narrows down the domain of discussion.

‘Purushottama’ is an excellent human being, though the word has other meanings too. Why is Rama an ideal man? Is it because he sets norms of good conduct for others to follow, or is it because he does not deviate from a contract, once made? The former is the more common interpretation, though the latter resonates more. For instance, the killing of Vali is a trade-off of dharma, ‘justified’ by the contract he had with Sugriva. Sita’s ordeal by fire or the killing of Shambuka can also be ‘justified’ by the contract he made for ruling the kingdom. To quote Sattar, ‘More and more, Rama seeks a righteousness not based in caste or life-stage (varnashrama), but in a higher truth which an individual can grasp through intuition... He moves from holding that a particularised individual dharma is the only basis for choice (obviously limited) to the more radical idea that dharma is the truth that transcends all boundaries.’ In other words, dharma is even above notions of maryada. Some have questioned Rama’s decisions and found it difficult to understand them. There are also those who have composed alternative Ramayanas in the process, unhappy with what Valmiki portrayed in his Ramayana. (Some of the essays do refer to other Ramayanas.) But this book is not about Rama and his decisions and their consequences, though there is an essay about Rama and the ascetic ideal. Sattar has explored that in an earlier book (Lost Loves, 2011).

This book is about others and their attitudes towards maryada and dharma. ‘I had intended to write about the so-called minor characters in the Ramayana, such as Dasharatha and Vibhishana. I also wanted to think about major characters, such as Ravana, Lakshmana and Hanuman, and their narrative roles’ (page 209). Thus, in this slim book with seven essays, we have essays on Dasharatha, Hanuman (there are two on Hanuman), Vibhishana and Lakshmana. But we also have essays on Ayodhya’s wives (meaning Dasharatha’s wives and Sita, not Urmila, Mandavi or Shrutakirti) and the women outside (Shurpanakha, Ahalya, Svayamprabha, Tara). Those who have read Sattar’s work know that she writes exceedingly well, in an engaging and reader-friendly way, without losing academic rigour. Since so many people are interested in the Ramayana and Rama, I think they will find this an engrossing read. But I don’t think this will be the last book Sattar writes on Ramayana and its characters. Her exploration of maryada and dharma will certainly continue and she will write more about the minor characters. Rabindranath Tagore wrote an essay (in Bengali) about Urmila, suggesting that readers want to know about Urmila, but not about Mandavi or Shrutakarti. Wait for Sattar’s next book. As for this one, it is an excellent read. Go for it and do read the others, in case you haven’t already. (Sattar’s The Mouse Merchant: Money in Ancient India (2015) and her translated Tales from the Kathasaritasagara (2000) are different in nature.)