The Literary Journeys of Shashi Tharoor

[ I ]

MANY YEARS AGO IN BOMBAY, ON A DAY SO HUMID even the air conditioners were sweating, I met a young writer of promise. Outside, the sky was overcast and the only colour visible was the pale blue scribble of the Arabian Sea on the horizon. Within, despite the murk and discomfort of that monsoon morning, I remember being impressed by the poise and self-assurance of the man who sat across the desk from me. The twenty-five-year-old Shashi Tharoor was some way from summiting any of the peaks he had decided to conquer, but you could see that here was someone who seemed destined to leave his impress on the world.

However, as is well-known, the only thing that is certain about promise, in life as in writing, is that there is a very good chance that it will be belied. Promising first novels peter out into a wasteland of aridity after a blistering start, literary careers that glitter at the outset prove to be meretricious, would-be stars are scuppered by bad luck, poor judgement, lack of application or life’s many distractions and setbacks—all these and more are not even worth remarking upon, they are so commonplace. In a terrific book (first published in the 1930s, and now forgotten), entitled Enemies of Promise, the English literary critic and writer Cyril Connolly wrote (in a play on the proverbial saying), ‘Whom the Gods wish to destroy, they first call promising.’ In ‘The Charlock’s Shade’, the second section of the book, and the part that is, by far, the most interesting, Connolly inveighs against the various pitfalls that lie in wait for the literary novelist. Among them are early success, journalism, and politics, all of them ‘tares’ that are guaranteed to choke the promise of most writers. He was not far off the mark, but he had reckoned without the likes of Shashi Tharoor, who succeeded early as a literary novelist, while also making his mark on journalism and politics, instead of being tripped up by them.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A couple of years after our first meeting, I moved careers (from journalism to publishing) and cities (from Bombay to Delhi) and it was then that my professional relationship and personal friendship with Shashi properly began. In the 1980s, long before internet routers, PCs, or laptops were in use you would invariably find piles of manuscripts printed on A4 sheets of paper on the desks of writers, agents, editors, and publishers. It was in this form that I first read The Great Indian Novel, Shashi’s debut novel, which was published in 1989. Ripping open the envelope that the courier had delivered, and taking out the manuscript, I settled down to read, but was wholly unprepared for what came next. Within minutes, I was swept away by a veritable cataract of words that sparkled, fizzed, foamed, and eddied with humour, insights, erudition, playfulness, and energy.

Indian literary writing, past or present, is not known for its humour, most of it is serious and worthy, with some notable exceptions like the work of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer in Malayalam, Harishankar Parsai in Hindi, and RK Narayan in English. Even more scarce are examples of satire and what I was reading was a masterpiece of satire. Bolted on to the framework of the Mahabharata (the ‘Great India’ of the title), it was a retelling of how India attained independence from a brutal colonial regime and how the country fared in the first few decades after Independence. It was funny, stylish, and insanely clever, history twisted into myth, twisted into the argot of the twentieth century, twisted into a narrative that moved at warp speed. What the author was attempting to do was nothing less than tell the story of modern India in a unique and wholly original way. In his words: ‘This is my story of the India I know, with its biases, selections, omissions, distortions all mine…. Every Indian must forever carry with him, in his head and heart, his own history of India.’ What inspired his fictional debut? He says:

‘Realizing that the only writing I was doing, all for newspapers and magazines, would end up being discarded with the week’s trash, I decided I had to write something more enduring—a book. It was while reading P. Lal’s ‘transcreation’ of the Mahabharata that I was struck by its immediacy. It had been reinvented and retold for centuries till about the fourth century after Christ; why did we stop, I wondered? And what would a twentieth century retelling of the Mahabharata deal with? The struggle for freedom, of course. Could I take two familiar tales—that of the epic and of the nationalist movement—and merge them to tell a third? I decided to try.’

As a feat of literary creation, The Great Indian Novel, published when the writer was only thirty-three, was a masterpiece. It had about it a certain effrontery, and the sort of risk-taking that in any field of endeavour separates the best from the rest. Nobody had ever attempted anything like this novel in Shashi’s peer group (Allan Sealy’s The Trotter-Nama, while epic, funny, and chock full of history, is essentially a family saga, so doesn’t really compare) or those who had preceded him in the annals of modern Indian literature with two outstanding exceptions—All About H. Hatterr by GV Desani, that is well-known but largely unread, and Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie’s towering masterpiece. The Great Indian Novel had many of the elements of Rushdie’s Booker-of-Bookers-prize-winning novel—history, humour, histrionics, torrential outpourings of words, and so on—but, unlike Midnight’s Children, the structure and foundation of Shashi’s novel were Indian myth and scripture and its content was unadulterated satire of the highest order. There are some masterpieces of fiction to be found in other Indian languages that take their inspiration from our classical literature but in English (at the time) Shashi’s novel was unique.

The Great Indian Novel swept all before it, and catapulted its author to global literary fame. The distinguished writer and critic Khushwant Singh declared that it was ‘perhaps the best work of fiction written by an Indian’. At once Rabelaisian and Chaucerian in its bones, it also drew inspiration from comic masterpieces like Don Quixote, The Good Soldier Švejk, and The Master and Margarita. Unsurprisingly, many novels of this sort were written in response to the brutality of dictators, tyrannical regimes, and the cupidity of rulers. The Great Indian Novel was no different. Through humour and satire it skewered British rule, but was unsparing in its criticism of Indian rulers as well. This is not to say that it was just an unending rant. In fact, like all great examples of satire, its punch was concealed in gloves of wit and good story-telling.

The Great Indian Novel was followed at regular intervals by other works of fiction, Riot, a more realistic novel, whose central theme was how sectarianism was destroying Indian society, and Show Business, a very funny, yet moving, novel set in the world of Hindi cinema. Besides the novels, there were short stories that appeared in various publications. I’d like to single one out for special mention, ‘Charlis and I’, which first appeared, oddly enough, in a book of non-fiction, India: From Midnight to the Millennium (1997), a superb account of contemporary India, that would go on to become one of Shashi’s most successful books. In the story, which I would rank among the very best short stories to be found in modern Indian fiction, the narrator, a big city youth, experiences caste prejudice and the changing nature of small town and village India. Set in Shashi’s native Kerala, it is poignant, beautifully paced, and features an array of well-developed characters. Another outstanding story that is somewhat similar in treatment and theme, ‘Death of a Schoolmaster’, is also set in Kerala, and deals with the changing reality of India outside the big cities. This made me wonder why, outside of Riot, which, while realistically written, uses a variety of stylistic literary devices—letters, dramatic monologue, notes from the field, and so on—to tell its story rather than a straightforward narrative, Shashi has never tried to write a conventional literary novel set in India, when it was clear that he was more than capable of doing so. When asked why, he said: ‘I’ve always believed that the very word “novel” required there to be something new about my literary endeavours: something new in both the tale and its telling. Each of my novels has involved a departure from the conventional in terms of both content and narrative style. I didn’t feel that “reversion to the mean” would be worth the time and effort. Why do what so many others have done already?’

[ II ]

SHASHI THAROOR WAS BORN TO MALAYALI PARENTS IN London, and grew up in Calcutta, Bombay, and Delhi, with frequent childhood visits to Kerala, which he regards as his ‘native place’, to use the precise and evocative Indian phrase for one’s place of origin. This is what he has to say about his Kerala heritage:

‘As a child… my experience of Kerala had been as a reluctant vacationer during my parents’ annual trips home. For many non-Keralite Malayali children, there was little joy in the compulsory rediscovery of their roots, and many saw it as an obligation. For city dwellers, rural Kerala (and Kerala is essentially rural, since the countryside envelops the towns in a seamless web) was a world of rustic simplicities and private inconveniences. When I was 10 years old, I told my father that this annual migration to the south was strictly for the birds. But, as I grew older, I came to appreciate the magic of Kerala—its beauty, which is apparent to even the most casual tourist, and also its ethos, which takes a greater engagement to uncover.’

His appreciation of, and renewed engagement with Kerala, would occur in the middle passage of his life. First, there were higher education and career imperatives to be dealt with. After taking a degree from St. Stephen’s in Delhi, he went to the US for higher studies; thereafter, he spent the next decades as an international civil servant working for the UN, rising to just one step short of the organization’s summit. After his UN stint, he embarked on the next phase of his career—a return to India, where he became a member of the Congress party, winning election to the Lok Sabha for three consecutive terms from Thiruvananthapuram. He served as a minister in Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s government and in the Opposition has led or been part of various initiatives. I will not dwell further on his career outside his writing life as this is not a biographical sketch of Shashi Tharoor, the professional, but rather an appreciation of Shashi Tharoor, the writer.

A precocious child, Shashi published his first short story, at his father’s urging, at the age of ten. Then followed a steady stream of stories, essays, and articles that he published wherever he could. As with a lot of accomplished writers, his forays into the literary life began as a reader. He writes:

‘My journey as a writer began with reading. Growing up in urban India in the late 1950s and 60s, my generation was probably the last that could read without the threat of other distractions. Television did not exist in the Bombay of my boyhood, and Nintendo or PlayStation were not even a gleam in an inventor’s eye; mobile phones and personal computers remained in the realms of fantasy. If your siblings were, as in my case, four and six years younger (and, worse, from a young boy’s point of view, female), there was only one thing to do when you weren’t able to play with your friends. Read. I read copiously, rapidly, and indiscriminately.’

Reading aside, another enormous early influence on his writing was his father, who inculcated in his all-too-willing son, a great love of words. Chandran Tharoor was a ‘word-game addict,’ writes Shashi, ‘from Scrabble to Boggle and acrostics in newspapers, and would make up games with my sisters and me.’ These early influences would never desert Shashi. And they would also ensure his life as a writer did not end as he began rapidly rising up the ladder at the UN, where he spent the first quarter century of his professional life.

[ III ]

LET’S GO BACK FOR A MOMENT TO THE CAUSTIC ANALYSIS of literature and litterateurs that I referred to earlier in this piece, Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise. We have seen how the critic was convinced that three of the most potent venoms that could kill a literary career were early success, journalism, and politics. By that prognosis, Shashi’s future as an author should have ended before it had even started. How did it survive and, more importantly, thrive? Says he:

‘I think George Bernard Shaw put it best: I write for the same reason a cow gives milk. It’s inside me, it’s got to come out, and I’d be in real pain if it didn’t. Writing is an essential part of who I am; it’s something I feel impelled to do, whatever the other demands on my time. So, despite holding some very demanding jobs, I wrote when I could: on evenings and weekends, on planes and trains, on scraps of paper resting against the steering wheel of my car while my wife did the weekly shopping. Samuel Johnson’s crack about how a hanging in the morning concentrates the mind applied to me: having to return to work in the morning meant I wrote at night with a will.’

There were always choices to be made: writing came at the expense of opportunities for entertainment, leisure, travel, friends. But Shashi ensured he made the time to write wherever he was. There is a revealing anecdote that I came across online many years ago that shows how exactly Shashi was able to keep putting out columns, articles, and books while maintaining a punishing schedule first as an international diplomat, and later as a serious politician. This incident dates back to when he was working for the UN. He was due to visit a Southeast Asian nation, and a young assistant who worked for one of the UN agencies there was deputed to present herself at the airport to provide any assistance the distinguished visitor might need for the few hours he would be spending in her city. After his plane had landed, and he had disembarked, she nervously approached him in the concourse and asked him if she could be of assistance to him in any way. In her online post describing the encounter, she said she was incredibly impressed when Shashi said all he wanted her to do was direct him to a quiet corner of the airport lounge that had a charger ready to hand so he could plug in his laptop and complete a piece he was working on. The story is illustrative of the enormous discipline it takes for a public figure to be able to maintain an output that would be the envy of a professional journalist or academic.

Be that as it may, what kept his career as a writer from capsizing was his determination to keep writing, no matter what. As he maintains in the essay ‘In the Beginning’:

‘At the end of the day, I tell myself that I am not defined by the positions I’ve held, and that my real legacy will come from the life I’ve led and the ideas and values I’ve stood for. These I have expressed in my own words, as a speaker and a writer. It is these words that will be my epitaph. When I am sometimes asked how I see myself, I tend to discount my public offices for the writing I do alone, in private. I’m already a former minister, I explain. One day, I’ll be a former MP. But I hope never to be a former writer.’

[ IV ]

THERE ARE THREE KINDS OF WRITERS COEXISTING within Shashi Tharoor: the writer of newspaper columns, book reviews, and magazine articles; the creator of literary fiction; and the author of heavyweight books of popular history, sociology, and current affairs.

He has mastered the art of writing for the broadsheets, periodicals, and, latterly, online media, and while much of this output is transitory, it is important to note that it’s done very well. A communicator nonpareil, he often takes it upon himself to explain complex ideas, matters of policy, history, and economic and scientific theory in clear, lucid prose for the layperson. In an era where most print media columns, editorials, and commentaries, as also social media postings, have been dragged down to the level of semi-literate or functionally illiterate readers and consumers, accessible, first-rate writing on complex and necessary subjects deserves to be celebrated.

The second sort of writing that Shashi does extremely well, although he hasn’t produced any major work in this area for two decades now, is literary fiction. Since 2001, he has published no fewer than sixteen books of non-fiction; the appearance of each prompts a fresh flurry of letters and messages from fans, asking for a novel. He confesses that he wishes he could satisfy them.

‘To write fiction, you need not only time, which is scarce enough in my life, but a space inside your head to create an alternative universe, and to populate it with people, places, and incidents that are as real to you as those you encounter in your ‘real’ daily life. It requires the building of a palace of illusions that exists only on the page and in your mind. But it’s a glass palace, that requires daily maintenance. If your job requires you continually to break the flow of your literary creation to attend to urgent calls, receive important visitors, make frequent trips for unpredictable durations, that glass palace is all too easily shattered. My laptops over the last two decades are littered with aborted fictions, novels begun but wrecked by the demands of my work. I realized non-fiction is safer; you can interrupt it, return to what you’ve written previously and pick up the thread of your argument. But with fiction, there’s a world you’ve got to create and live in, and if that’s shattered, you can’t go on.’

As I have already remarked upon his fiction, let me turn to the third form of writing that he excels at—superb non-fiction, written in a fluent style that informs and entertains while maintaining the highest standards of scholarship. Of the twenty-one books he has published this far, there are at least five books of non-fiction that will be read a generation from now—India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond (1997), a beautifully written, popular account of independent India; Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century (2012), a lucid and comprehensive book on Indian foreign policy; An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India (2016), a deeply researched and eye-opening book on how the British Empire looted India for several hundred years; Why I Am a Hindu (2018), a celebration of Hinduism’s eternal verities, and an attack on those who are perverting the faith; and The Battle of Belonging: On Nationalism, Patriotism, and What It Means to Be Indian (2020), the first major book on nationalism and patriotism written by an Indian writer since Rabindranath Tagore’s timeless meditation on the subject. To write one book that will outlive you is achievement enough but to write six or more is, by any yardstick, outstanding.

What is even more remarkable is that many of his books have racked up hugely impressive sales figures. Despite being exposed to the English language for hundreds of years, and by some accounts already home to the greatest number of people anywhere in the world who use the language in some form or the other (according to the noted grammarian David Crystal, some 350 million Indians profess to have at least a basic knowledge of English), India is pretty inhospitable terrain for the writer of serious non-fiction books and novels in English. Unless you peddle commercial fiction, historical or otherwise, the prospect of success for most literary and scholarly books is bleak. What’s worse, there is no sign of things improving, indeed we are going backwards, as illiterates and ignoramuses have begun to hold sway in many areas of endeavour in the country. In such a scenario, the fact that a book like An Era of Darkness has sold a quarter of a million copies in hardback is testament to Shashi’s gift of writing books on serious, even abstruse, subjects in lively prose, without sacrificing scholarship or dumbing down what he is attempting to put forward.

Aside from the pellucid writing and scholarship he brings to his non-fiction books, what sets them apart from most other significant works in the genre is the passionate conviction that underlies them. He avers:

‘As a writer...I have been more concerned about the substance of what I had to say, and the effectiveness of the way I say it, than the actual words themselves. My writings on world affairs, Indian history, and politics, and, of course, my fiction, require apposite words to express my ideas, but I had no doubt that it was the ideas that mattered.’

It would be impossible to summarize all the ideas that Shashi has held dear for most of his life, that will have to await his authorized biographer when his career is over, but, broadly speaking, his interests fall into two major areas: international affairs and foreign policy; and Indian history, politics, and current events, viewed, uncompromisingly, through a liberal, secular, and humanitarian lens. His great hero is Jawaharlal Nehru, whom he wrote a book about, and his outlook on many matters might be called neo-Nehruvian (though he doesn’t, for example, subscribe to Fabian Socialism, and is not agnostic as Panditji was, among other things). Like Nehru, his passion for his country is indisputable. Describing himself as a ‘congenital nationalist’, he writes: ‘India shaped my mind, anchored my identity, influenced my beliefs, and made me who I am. ...India matters to me and I would like to matter to India.’

The India that animates most of Shashi’s works, the India he extols, and the India he has fought to preserve, is best expressed in three passages that are quoted below, from various books and speeches.

- The singular thing about India is that you can only speak of it in the plural. There are many Indias. Everything exists in countless variants. There is no single standard, no fixed stereotype, no one way of doing things.

- In our democracy, this land imposes no narrow conformities on its citizens. The whole point of Indian pluralism is you can be many things and one thing. You can be a good Muslim, a good Keralite, and a good Indian all at once.

- The idea of India, as Tagore and more recently Amartya Sen have insisted, is of one land embracing many. It is the idea that a nation may endure differences of caste, creed, colour, conviction, culture, cuisine, costume, and custom, and still rally around a consensus. And that consensus is really around the simple idea that in a democracy you don’t really need to agree— except on the ground rules of how you will disagree.

Over the course of his writing and political career, despite being attacked and vilified by the purveyors of religious fundamentalism, obscurantism, and proto-fascism who currently occupy the commanding heights of our politics, media, bureaucracy, and institutions, Shashi has never wavered in his beliefs nor displayed the shameless betrayal of their convictions by many former liberals, leftists, secularists, and political opportunists. It is this that makes his writing and public pronouncements valuable in our dank and morally defunct times.

Beyond content and ideas, Shashi’s writing style is distinctive. His fondness for wordplay—especially puns, alliteration, clever coinages, and all manner of bon mots—is on display in pretty much every form of his writing. So is humour and a lightness of touch. He attributes this to the influence of literary idols such as that peerless master of English prose and humour, PG Wodehouse. He was also an early admirer of Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Milan Kundera, and Philip Roth. But his writing is very much his own.

Over time, Shashi has gained a reputation for being fond of using big and polysyllabic words, but it’s a misperception to think that these are his stock in trade. While it’s true that he will, on occasion, use a word that can make you reach for a dictionary, he is an advocate of using simple diction and short words to convey thoughts and ideas. He writes in an essay entitled ‘The Wordsmith’:

‘I try not to use unfamiliar words unless I have to. Though it is sometimes fun to use complex, obscure words to add flavour to writing, I tend to advise writers to, in general, follow George Orwell’s rule: never use a long word where a short one will do. Writing is best when it is direct, clear, and concise.’

[ V ]

WHEN I BEGAN WORKING ON THIS LITERARY PROFILE OF Shashi Tharoor, the first image that came to me was something I learned about in college when I was studying to be a botanist. I have retained very little knowledge of the plant world, but I remember being fascinated by a phenomenon called Brownian Motion (BM). First described by a botanist, and later becoming one of the building blocks of physics (Einstein studied it, as did several other top scientists), Brownian Motion describes the random movement of particles found in liquids or gases. These particles are in continuous motion, swarming, colliding, shooting off in different directions, never at rest, always in flight. I fancied that this is what a graphic representation of Shashi’s mind would look like with an important difference—the movement of particles in BM is random whereas I doubt, on the evidence we have, whether anything about Shashi’s output as a writer is accidental. It’s quite apparent that there is a furious churning going on in his mind at all times, his is a restless intelligence, and this sometimes manifests itself in spontaneous insights or unexpected comments, but there’s nothing that’s less than considered about his books, columns, and other published work.

At a conservative estimate, Shashi Tharoor has probably published about five million words over the past fifty years or so. I asked him whether he had ever felt he was too prolific and whether he might have written better if he hadn’t written so much. In reply, he cited a reviewer in the Washington Post who once wrote of what Shashi might have accomplished if he had only given up his day job; that said, he was unrepentant about the way he writes. ‘I’m a human being who reacts to the world I see around me,’ he maintained. ‘Some of that reaction I show in my writing, and some in my work, whether as a UN official or an elected politician.’ He is the first to admit that this does not leave him the time to polish his prose as another writer might; he writes rapidly, since he has other work to get back to. ‘To borrow from the American humourist AJ Liebling,’ he said, ‘I write faster than anyone who writes better, and I write better than anyone who writes faster.’

What I find remarkable is how well much of this copious output holds up, years after it was first published. And, at the centre of this great welter of words are his masterpieces, the foundation stones of the literary house of wonders that this peerless Indian writer has been able to create. As I come to the end of this appreciation of Shashi Tharoor, the writer, I would like to apply Pablo Neruda’s words (about a writer whose cause he was espousing) to Shashi’s work: ‘Anyone who hasn’t read (Julio) Cortazar is doomed…something similar to a man who has never tasted peaches. He would quickly become sadder, noticeably paler, and probably, little by little, he would lose his hair.’

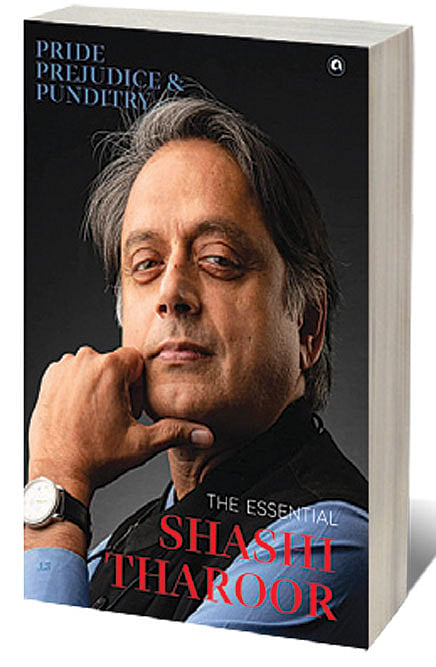

(This is an edited version of the introduction by David Davidar to

Shashi Tharoor’s latest book, Pride, Prejudice, and Punditry:

The Essential Shashi Tharoor | Aleph | 600 pages | ₹ 999)