The Gifts of Gieve

IN HIS 1976 poem, ‘The Ambiguous Fate of Gieve Patel, He Being Neither Muslim Nor Hindu in India,’ poet, playwright, painter and polymath par excellence Gieve Patel made a striking opening gambit: “To be no part of this hate is deprivation.” He went on to explain, without explicitly calling out his Parsi identity, the liminal position he occupied as a member of his community in this country, a minority among other minorities in contemporary India.

“Never could I claim a circumcised butcher/ Mangled a child out of my arms, never rave/ At the milk-bibing, grass-guzzing hypocrite/ Who pulled off my mother’s voluminous/ Robes and sliced away at her dugs,” Patel continued, before concluding on a note of despair and bitter self-mockery: “Bodies/ Turn ashen and shrivel. I/ Only burn my tail.”

Imageries of graphic violence and severe mutilation were as much a part of Patel’s poetry as they are of his art. Born in 1940, he was one of the most involved observers of India’s troubling modernity until his death on November 3, 2023, at the age of 83. As Parsis, Patel and his people may not have been the obvious victims of communal poison. However, as an artist of immense compassion and empathy, Patel remained an equal stakeholder with the wretched of the earth, chronicling their plight in his poems, plays, paintings and sculptures with haunting acuity till the end of his life.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Patel was a committed crusader for the vulnerable and neglected, men and women who lived on the margins of society, erased or silenced by the march of progress. As a trained physician, who ran clinics in rural Gujarat, Maharashtra, and later in Bombay (now Mumbai), he wasn’t a stranger to suffering. And as an artist, he could probe deeper into the recesses of humanity, recording his protest at the indignity hurled at other bodies, through words and images.

In his work, Patel spoke up against the dichotomies of rural and urban existence, the injustice that unfolded in each domain. Like Hanuman, who created havoc when made to parade the streets of Lanka by Ravana with his tail on fire, Patel left the embers of his sensibility simmering through the wilted humanity of the subcontinent, torn asunder by forces of division since the Great Partition.

Instead of being a silent spectator, Patel chose to be, on his own terms, a conscientious objector.

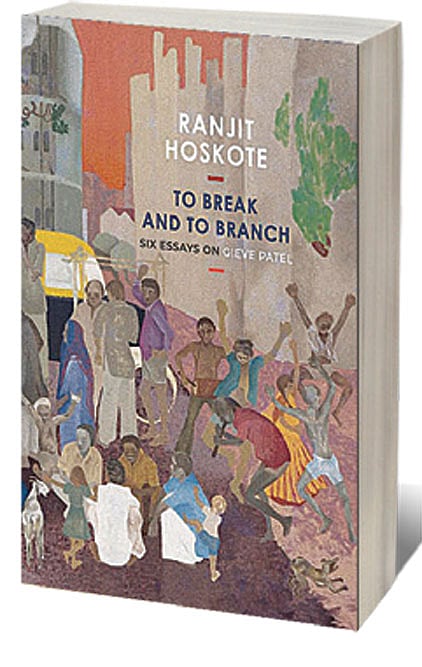

It’s easy to overlook the contribution of artists like Patel and his contemporary Sudhir Patwardhan (born 1949) to Indian art, both of whom were masters of figurative painting, amidst the clamour of trends that dominate auction houses. Conceptual and experimental pieces, with their (often) sensational appeal, loom over the carefully calibrated cerebral styles of a Patel or Patwardhan, who dwelled on the nuances of paint and problems of representation that go back to an earlier era of artistic practice. It is for this reason, among many others, that poet and cultural critic Ranjit Hoskote’s latest book , To Break and To Branch: Six Essays on Gieve Patel stands out luminously.

Beautifully designed and published by Seagull Books, this slim volume brings together essays by Hoskote on Patel’s artistic practice. The offering is framed by a moving introductory tribute to Patel, where Hoskote writes about the 37-year-old friendship he shared with the artist.

If their relationship began with a young Hoskote meeting the extraordinary Patel at their common mentor Nissim Ezekiel’s office in South Bombay, over the years it ripened and evolved into an intellectual companionship that only a lucky few can find, share, and sustain. Hoskote was to Patel what art critic Michael Peppiatt was to painter Francis Bacon—a protege, critic, younger colleague and confidant, who happened to be privy to some of the most intimate struggles of his artistic process.

Hoskote’s evaluation of Patel’s work, therefore, assumes the form of a double helix: the critic’s view of the artist’s progress over the years gets intertwined with the critic’s perception of his own growth. Prolonged exposure to the work of an artist not only gives the viewer an appreciation of stylistic shifts but also opens up newer meanings, details that have eluded the eye even after years of seeing.

In one of the finest works of art criticism, The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing (2008), art historian TJ Clark wrote about his experience of looking at just one painting, Poussin’s Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake, over weeks, during which both art and observer begin to commune with each other in a language unheard by the ordinary others. In Hoskote’s essays, too, we sense his evolving engagement with Patel’s work as a whole, a keen alertness to emerging patterns, his understanding of the intertextuality of Patel’s writing and art-making, and a heightened ability to see details that a less informed onlooker would miss.

A fine example of the latter is Hoskote drawing our attention to the Telugu script on a letter being written by a scribe for an unlettered man in The Letter Home (2002). As a whole, the composition sets up what Hoskote calls “the asymmetries of communication and distance, the inequalities of expertise” with a beautiful economy. But the detail of the Telugu script opens up another layer of referentiality within Patel’s world—his connection with Andhra Pradesh, links with J Krishnamurti and Rishi Valley School, as well as his ability to narrativise a seemingly ordinary scene with the opening address of the letter.

Hoskote’s deft reading of the scene pushes the viewer to reckon with the appeal of the subtle and unseen, even as it’s in the nature of the eye to be drawn to what is dominantly visible.

TO GO BEYOND the surface of Patel’s paintings, the viewer must pay close heed to the shifts in tone, texture and temperature of his canvases. Like Patwardhan, who is sometimes thought of as an artistic twin to him in terms of sensibility, Patel was an interpreter of the modern metropolis. Both men bring to their work a profound need to represent the “unromanticized middle- and working-class life,” as Hoskote says, a slice of society that seldom finds its full expression in Indian modernism.

Indeed, Hoskote sets the premise in the first line of the opening essay, ‘An Economy of Violence’: “Gieve Patel is not one of those painters,” he writes, “who evade grief, violence and affliction of their society by resorting to elaborate symbolism.” Writing about Patel’s “anti-portraits”, being part of “a subversive Gallery of Man,” Hoskote draws our attention to “the blood-quickening viscerality of the act of viewing.” “We feel the throb of a universal vitality,” he adds, “an unambiguous and palpable thingness.”

Even though the paintings are reproduced and reduced manifold in scale, they besiege us with the force of the originals. Crushed Head and Drowned Woman, both dating back to 1984, are, by far, among the most haunting close-ups of corpses ever created in the history of art. Both scenes are regarded with a clinical eye by Patel the physician, then transmogrified into something perversely rich by Patel the artist. There may not be dignity in these deaths, but he still makes them count by forcing strangers to look at these distorted faces, the remarkable solidity as well as fragility of the human body.

Crows with Debris (1999), yet another death-haunted vision, unpeels the film of familiarity from a familiar scene. A murder of crows takes their pick from the corpse of a rat, split into half by a vehicle on a highway. Apart from the tyre marks, we notice a used condom on one side, and a broken barbed-wire fence on the other. This tapestry of life and death, pleasure and pain, weaves in layers of meaning, from crows and their role in Parsi funeral culture to the theory of the survival of the fittest to the irrevocable circularity of the food chain.

Despite this preoccupation with decay and destruction, Patel infused his paintings with warmth and tenderness. Like Patwardhan, he used the street as his theatre, where some people gather to perform their roles and are, in turn, observed by an audience of others. In all his street scenes, Patel himself is the primary audience, whether he captures a little girl feeding an armless beggar at a bus stop or a family of mourners around a man who has collapsed on the road.

Yet, the artist is never entirely absent from the scene himself. As Hoskote sees it, Patel remains a “complicit observer” all along. “To me, [the adjective complicit] foregrounds those nuances of guilt at representation and voyeuristic furtiveness of observation, that acknowledgement of the shared onus of existence and the push-pull between belonging and remoteness, which characterize all honest figurative art.”

THE RICHNESS OF Patel’s work comes from its awareness of its intertextuality, the links he forges with his writing as well as those of others, bolstered by his hawk-eyed observation skills. Behind two of his best-known paintings, Peacock at Nariman Point (1999) and Embrace (2016), lie two rather quotidian events, both reported in newspapers. While drawing our attention to the quaint backstory of these compositions, Hoskote invites us to probe deeper, to imagine and speculate the mystery behind the “man clutching at a peacock as if it were his soul leaping out of his body.”

Like all great art, Patel’s work assumes form and meaning through the eye of the beholder, who may or may not be aware of any subtexts. In his Daphne and Eklavya series, both from 2006, Patel uses terracotta, bronze, and fibreglass to bring to life stories from myths and epics. These sculptures of bodies morphing into vegetation or being disfigured are, on the one hand, what they starkly present to the eye: intimations of violence and suffering. On the other hand, these moments of transformation open deeper philosophical inquiries when read with Patel’s oeuvre as a poet.

In the poem ‘Squirrels in Washington’ (1991), for instance, Patel revisits Daphne as a marvel, a being on the interstices of life forms: “Passing/ From woman to foliage did she for a moment/ Sense all vegetable sap as current/ Of her own bloodstream, the green/ Flooding into the red?”

He brings the same rigour of inquiry into his Looking Into a Well and Cloud series, as he grapples with representing water or capturing the evanescent flight path of clouds.

Patel’s forever questing spirit, his ability to live with “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” (to borrow from poet John Keats), not only accords to him a unique vantage point in Indian art, but also a complexity of insight that helps make sense of our complicated times.