The First Heroine

IN A WORLD far removed from now, the first Malayalam film was produced and released in erstwhile Travancore on October 23rd, 1930. But what was the beginning of a great history, the first screening of Vigathakumaran (Lost Child) at the Capitol Cinema Hall in Trivandrum, ended in disaster for some.

The first heroine of Malayalam cinema, PK Rosy, was forced to flee her hometown, Trivandrum, in the ruckus raised by the casteist forces. Because, she was an untouchable, a Dalit, playing the role of an upper-caste woman in the movie. She was already a pioneer in taking on female roles in the folk form Kakkaarissi and had had her setbacks there too.

She was never heard of again.

When Vinu Abraham, a writer of short fiction in Malayalam, stumbled on this piece of ignored history of Malayalam cinema, he was intrigued enough to chase the tale of the ‘Lost Heroine’. Some material compiled by dedicated researchers was available but it had more gaps than information. And not even a mugshot of the lady was to be found. But the story of Rosy, by then, demanded to be documented in fiction. And Vinu Abraham admits he understood the need for liberal doses of imagination to complete his mission.

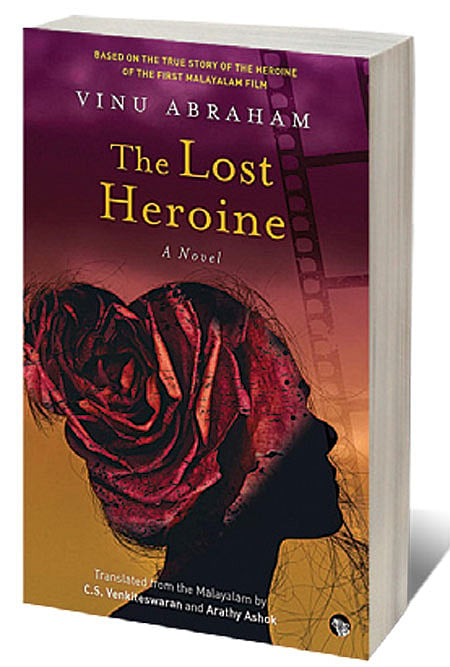

The novel Nashta Nayika (Lost Heroine) came out in 2008, and since then, Rosy’s story has fused into the Keralan culture-o-scope, both aurally and visually. The biggest take-off of the novel was, perhaps, the movie Celluloid (2013), which collected awards galore. A delectable and fully justified English translation of Nashta Nayika (2020), by CS Venkiteswaran and Arathy Ashok, brings the story of PK Rosy to the non-Malayali audience.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The well-preserved sense of ‘local’, and the light and non-intrusive approach to translation works well. The style of multiple translators is worked seamlessly into the text.

The innate culture of a language has its subtexts which can be lost in translation. Alternatively, this is seen adapted suitably into the tapestry of the target language. It’s the translator’s challenge to keep a fine balance. A ‘literal’ translation, where one ‘hears’ the original tongue, does bear the risk of the text sounding awkward in English. As AK Ramanujan says, ‘A translator hopes not only to translate a text, but... to translate a non-native reader into a native one.’

In the particular case of texts transported from Indian languages to English, there often is displayed a sheer necessity to anglicise the bouquet of the argot. Arguably, this dilutes the flavour of the culture in focus. Metaphors and sentence structures also vary from language to language.

Lakshmi Holmstrom has famously preserved the ‘Tamilness’ of Salma’s The Hour Past Midnight in her English translation by retaining metaphors and not altering linguistic structures of the source language. Her retaining the metaphor of the ‘tamarind branch’ for ‘a catch’ is an example. This maintains the case for the untranslated and unannotated word and also for two levels of translation: the popular translation as we have known it and an academic translation as is increasingly endeavoured.

The Lost Heroine has likewise conserved the flavour of the original text in Malayalam, with lexis like ‘sayip’, ‘Koche’, ‘Penne’, ‘Edi’, ‘vaidya’ ‘tharavad’, etcetera, with random capitalisation as quoted. And therefore, the references to the ‘porridge for supper’, ‘gruel’, ‘boiled asparagus and chilly chutney’, ‘tapioca and fish curry’ comes across as dissonant. The cultural context of cuisine and its role in placing the protagonist in the intended social band are too precious to let go in translation, especially in a period story.

Also, the mother is referred variously as ‘Amma’, ‘Ammachi’ and addressed once by Rosy as ‘Mother’. Again, when the upper-caste moral brigade foul-mouths Rosy, it’s ‘aruvanichi’ at various places and ‘whore’ and ‘slut’ at others. An editorial consistency would have saved the translation from such glitches.

Rosy’s story is one that should be announced to the wide, wide world. Lost Heroine rises finely to this occasion.