The Anatomy of Outrage

EVERYDAY UGLINESS, be it of form or otherwise, is unpalatable to and largely ignored by the ‘normal’ human. But for the dehumanised individual it’s a ‘terrible beauty’. Indu Menon’s short fiction zooms in on exactly that awe-filled pulchritude in the contemporary world.

A title like ‘The Lesbian Cow’ intrigues a reader enough to pick up the volume. And then, it delivers the promise. The book, as the translator cautions in his introductory note, is not for the fainthearted. Sixteen stories, mostly macabre, are narrated without an iota of hypocrisy. The torch shines mostly on the female, the oppressed and the visibly invisible hanging on at the lowest rung of the ladder as hierarchy bares its teeth from above.

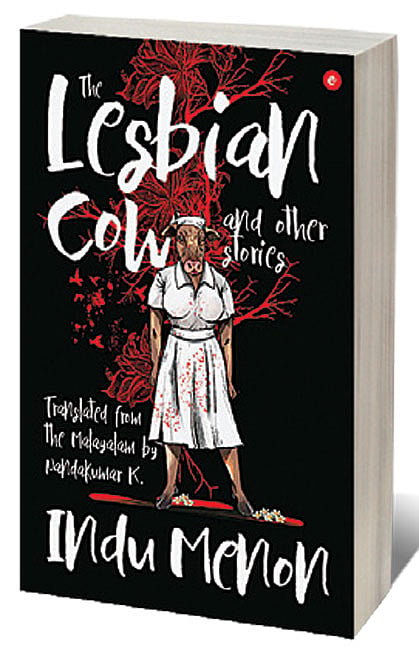

Etched in blood and gore at one end of the spectrum and the gentlest of passions at the other, the text gives no consideration to accepted aesthetics. Rather, there is a conscious endeavour to evoke all the five senses, to the utmost limit. And that starts right with the cover page.

The cover is nothing short of brilliant. A bovine face in a female human form, complete with not one but twin udders, stares back at the reader. It wears a blood-spattered nurse’s uniform. The stance of the body is aggressive; feet apart, radiating electric, even sexual, energy. At its feet lie pretty white frangipanis, symbolic of the hidden strengths of the seemingly delicate blooms. And that sets the pace and tone for the many unsafe spaces navigated by the protagonists inhabiting the pages. The prose is unquestionably ingenious, and the stories drawn across a range of imaginations; the rules of the protagonists being their own.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In the title story ‘The Lesbian Cow’, Nandini Gaumata, a nurse with an unlovely physique has a penchant for young Mehrunnisa’s body.

This plot is placed right within the story of an inter-religious live-in relationship, which goes through surreal layers of local fables intertwined with hints of contemporary events.

The opening story, ‘The Creature’, is a heart-rending saga of racism. The reigning politics of Tribal land grab sets the tone of the narrative. ‘D’ inventively juxtaposes Foucault’s Damien narrative and a Sri Lankan tale to point a finger at the political systems and structures of power.

‘A Story Posted in 1975’ curiously opens with a Vividh Bharati report about how ‘he had perished in a plane crash’. It takes on the birth-control horror stories during Emergency and asks a still-valid question, ‘Who in India wants Ghulam Nabi’s children?’ In ‘Chaklian’, the writer drills deep holes in your heart when a father uses his chisel on human skin to make his daughter a pair of Cinderella’s shoes.

The stories move ahead on that note and in the midst of this rollercoaster ride, the reader gets to breathe easy as a surprisingly tame tale pops up. ‘The Autobiography of a Movie Extra’ does not fit in with the defining tone of the book. It’s about a junior artist whose high morals stand in the way of her ambition and how her daughter handles the same situation several years later.

The Malayalam anthology of stories was published in 2002, and the translation has come out after nearly two decades. But the fresh-off-the-mint feel of the stories are astounding, reiterating how universal and contemporary they are. Politically incorrect and provocative they stand the test of time.

The translator, Nandakumar K, deserves a standing ovation for the excellent rendition into English. Menon’s narrative in Malayalam is fairly layered and the nuances of the Malayalam hold out more labyrinths to navigate. Menon’s craft is chosen to match her plots, and that demands careful translation. Yet, there is not a line or story that suffers from fluctuations in tone or text, neither is readability compromised in this highly recommended book.