The Afterlife of Socialism

WHEN JAWAHARLAL NEHRU died in May 1964 nearly one out of every two Indians was poor. It would take another 30 years before a dent could be made in poverty. Reducing multidimensional poverty required India to wait until the 21st century. In that sense the original rationale for economic planning in India—quickly increasing the rate of growth so that Indians could have a better life—was not achieved during Nehru’s life.

The “successes” and failures of Indian planning and, in particular, the Nehruvian developmental model, have spawned a virtual industry. Over the past 70-odd years the who’s who of economics has taken a shot at explaining India’s planning experience. There have been favourable analyses and critical ones as well. But the consensus is that planning did not live up to the hope it had kindled. India, when compared to its peers in Asia, did not perform well enough to quickly eradicate poverty and give a decent standard of living to its people.

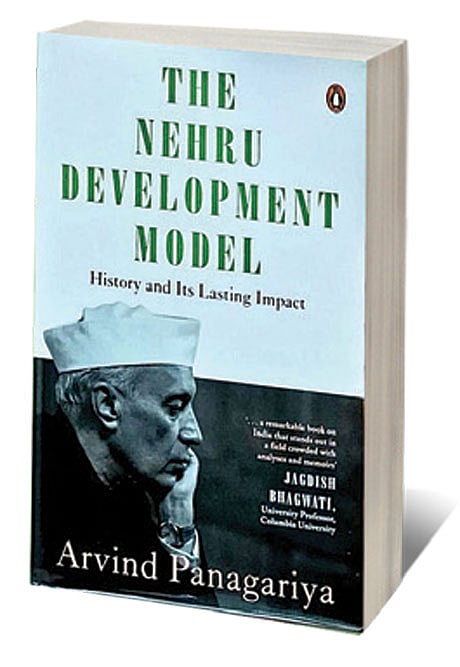

In The Nehru Development Model: History and Its Lasting Impact Arvind Panagariya examines the economic record of the Nehru model and its long-term political consequences. He is well-placed to examine this economic history as he is a long-term analyst and observer of those economic events and later a participant in policymaking as well.

The record of planning is unflattering. India’s growth was sclerotic at the best of times and even when it grew fast it could seldom keep pace with what was needed for the wellbeing of citizens. The strategy India adopted, developing heavy industries first instead of first going for light industries, jammed growth. The investment required for these industries was massive and the returns were meagre. This became evident during Nehru’s lifetime. Less than a year before his death, there was a heated debate in the Lok Sabha where Minoo Masani pointed out the very heavy expenditures on the public sector industries and the exceptionally poor returns from those investments. The truth was that even decades after these industries were established, income distribution was so skewed that output from these industries could not be absorbed into the Indian economy. This problem was not even considered as a binding constraint by the planners.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

What makes Panagariya’s book stand apart is its equal emphasis on the political legacy of the Nehru Development Model. Usually, analysts keep the economic consequences of planning and its political consequences in hermetically sealed compartments. This makes no sense as economic decisions are not made in isolation from political calculations. The Indian experience shows that these two domains interacted in complicated ways, but their overall effect was deleterious for India. The first part of political consequences that flowed from the socialist experiment was that it proved almost impossible to undo once it was rolled out. In the three-odd decades from the start of the Second Five Year Plan (1956) to the arrival of Rajiv Gandhi (1984), it was considered heretical to even question economic planning. Rajiv Gandhi realised that to his cost within two years of coming to power. Such is the nature of Indian political cycles that unless reforms are undertaken carefully, the nature of politics—the annual calendar of elections, the assorted “scandals” and random events—can ground the best planned reforms. It took Narasimha Rao, perhaps the wiliest of Indian politicians (in a positive sense) to undertake market reforms while saying all along that he was a steadfast adherent of Nehruvian planning.

What makes India’s socialist economic experiment deeply pernicious are its political aftereffects that persist until today. It is an interesting thought experiment as to where India would be if it had chosen the light industries path like Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries? Chances are that by now India’s middle-class population—the real one and not just the numerical slime that is a statistical artefact of consumption expenditure differences between top and bottom deciles—would be a thick layer and the calls for redistribution and affirmative action would have few takers. But India chose the heavy industries path, poisoning its politics for a long time.

The 21st-century socialist politics in India, which has a resonance among certain sections of voters and is the mainstay of important parties, is very different from its 20th-century variant. The heavy industry strategy was an adaptation of Marx’s “two department” model and was geared on the assumption that production and output mattered. The 21st-century edition is based purely on redistribution without any vision for production. The results will lead to anarchy if this “socialism” gets a shot at power.

It is interesting to ask what remains of the three pillars of Nehruvian socialism 73 years after the First Five Year Plan and 60 years after he died. Of the three—emphasis on heavy industries, progressive expansion of the public sector and self-sufficiency—one idea has made a comeback of sorts. In the summer of 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic raged across the world, Prime Minister Narendra Modi outlined the idea of Atmanirbhar Bharat or self-reliant India. But unlike the 1950s, the context was different. There was no ideological undertow behind the new idea of self-reliance. India, like many other countries, is now experimenting with state-supported industrialisation. The Performance-Linked Incentives (PLI) schemes now span dozens of key industrial areas even as the Centre is committing huge expenditures to manufacture semiconductors.

Does this mark a return of dirigisme a la Nehru? Even if it is not quite a return to the commanding heights the new emphasis on industrialisation has been criticised. There are observers who decry this trend and say that India will be best served if it focuses on services. Panagariya, too, has noticed this and towards the end of the book he issues a mild criticism: “The record of the Modi government has not been without blemish, however. In particular, it has revived import-substitution industrialization (ISI), which remains popular among its rank and file.” The criticism is not ideological as he says in the very next line that the current pursuit of ISI is not anything like the one that India had pursued until 1991. His conclusion, however, is a cautionary note: “Nevertheless, the belief that a country can simultaneously expand total exports while shrinking its imports is not only damaging to the efficiency of the allocation of resources but also conceptually flawed.”

It is tempting to compare India during the Nehruvian and Modi eras. In both periods, India can be viewed as a “project-state,” an idea used by historian Charles S Maier (in The Project-State and Its Rivals: A New History of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries) to describe states with ambitious agendas for transforming political institutions, civil societies and even mentalities. But beyond that, the comparison vanishes. This is largely due to a single factor: pragmatism. Nehru had little or none of it; Modi is wholly informed by it. The differences can be seen virtually across every realm of governance, from foreign policy and, what is germane to Panagariya’s book, economic choices and outcomes. Nehru had systematic plans, but his India had precious few resources or the political wherewithal to implement these plans. India of the present time has managed to remain on a high growth trajectory in an age of pandemic and wars. In a world short on trust—the foundation of trade—it is not surprising that mercantilist ideas and protectionism have returned. Who could imagine, even two decades ago, that the US, of all the places, would put industrial policies in place. If India is indulging its bit of spending to industrialise, it is only pragmatic that it does so. There is nothing Nehruvian about it.